Alfonso Cuaron’s remarkable film Gravity has just won the BAFTA for outstanding British Film, cinematography, music, best director and visual effects. Not bad for a film depicting an outrageously difficult location: space. The script called for a real-life actor flying through simulated space, tumbling, careening, moving through the microgravity of the insides of a flaming spacecraft; projectiles orbiting in three dimensions; the Earth below; a sun beyond; a vacuum everywhere. How were the remarkable shots made? A multitude of green screens and actors on wires? In fact, much of it was planned and created in Soho, London.

Initially the director planned to use conventional methods to capture the freedom that space gives the cameras and actors. But with wires and harnesses, “you feel the gravity in the face, you feel the strain,” Cuarón, the Director said. They tried the infamous “vomit comet”—a specially fitted airplane that flies in steep parabolic arcs to induce a few seconds of weightlessness inside the open fuselage, which was used to great effect in Apollo 13. Cuarón found it impractical: “You’ve got a window of twenty seconds if you’re lucky, and you’re limited by the space of a 727.” So they flew to San Francisco to view robots as stand-ins for the actors. They tried motion capture. They considered creating CG actors but nothing seemed quite right. They had to invent the technology that would allow the film to be made.

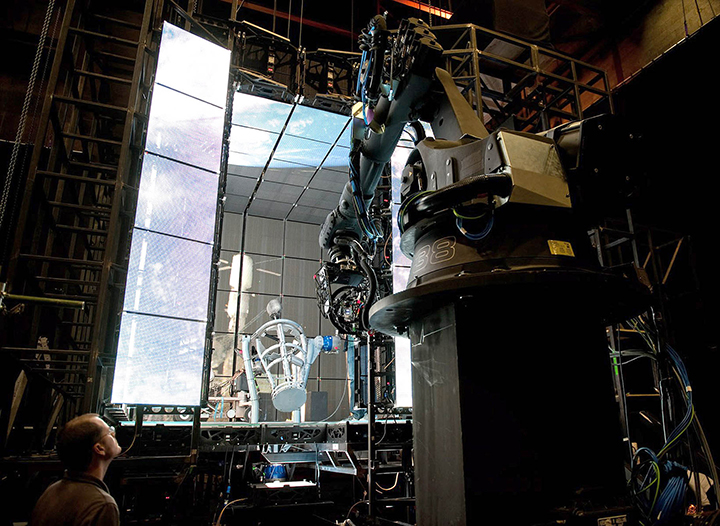

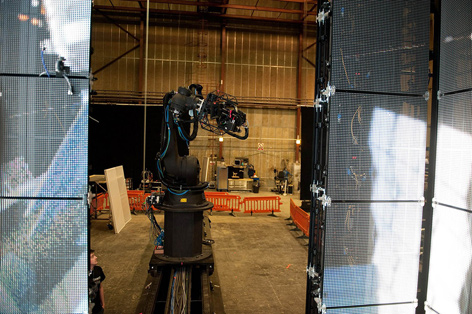

"First of all we had to work out a way of surrounding the actor by lights everywhere, and yet still being able to get the camera to be active and not have the lights getting in the way," explains Webber, Visual Effects Supervisor. Director of photography, Lubezki concerned himself with the light in space. "Light in space isn’t like any other light, you know, because it’s unfiltered." He was at a Peter Gabriel concert when he had his eureka moment of using LED lights. The team ended up building a 10 x 10 foot light box that could extend both height- and width-wise, studded with LEDs. Two years and 1.8 million LEDs later they could control the brightness of each of every single one of the LEDs to get the colours and the position of all the light effects. The amazing complexity of colours that LED lights can give, means that the actors could be lit more realistically than with conventional lights. They could replicate light reflected from the earth, the moon, plus sunlight and starlight. The quality of light was rich and varied; when they were over the ocean, there were cool blue lights, and over North Africa there were warmer colours coming from the desert.

But another puzzle remained: how to recreate zero gravity? To simulate free floating space cadets, Cuarón enlisted the help of automotive manufacturing technology. The robots used on production lines have the precision of movement that even the steadiest grip can't replicate for camerawork. So with some modifications, the actors were photographed inside the light box, attached to the robotic device. They remained relatively static whilst the cameras moved around, achieving the illusion that it the actor that is moving. The cameras could also zoom in and out from the face. “It’s like a giant TV on the inside of the box,” Webber said. “So that gave the actors a sense of the environment around them.” If the scene involved Earth as the source of light, the actors would see a representation of the Earth inside the box.

For the space scenes, the majority of each shot was computer generated, all done through backward-engineering. They recorded the actors’ faces, Sandra Bullock and George Clooney, then created a world around them; space suits, helmets, visors and more. That meant pushing CG capabilities beyond the fantasy genre of Avatar or Transformers, where imperfect representations can be forgiven more easily.

As for the things that physical set builders would normally make in a film studio, these were all done by computer generation. The International Space Station, the space debris, the space suits were all made by visual effects artists at Framestore, and every object and set was created in phenomenal detail. The actual International Space Station ISS is made of 50 pieces sent up over the last 25 years, all with a different purpose and manufacturer. These were all carefully rebuilt using CG and source reference photos. Using software called Image Modeller they used existing images, selected matching points on different photos of the same thing and keep repeating the process until a 3D camera view was created, which CG modellers could then model from. Whilst closely based on ISS dimensions and photos, the interior sequences allowed more creativity with the exact props and positions being changed to suit the narrative.

As for the things that physical set builders would normally make in a film studio, these were all done by computer generation. The International Space Station, the space debris, the space suits were all made by visual effects artists at Framestore, and every object and set was created in phenomenal detail. The actual International Space Station ISS is made of 50 pieces sent up over the last 25 years, all with a different purpose and manufacturer. These were all carefully rebuilt using CG and source reference photos. Using software called Image Modeller they used existing images, selected matching points on different photos of the same thing and keep repeating the process until a 3D camera view was created, which CG modellers could then model from. Whilst closely based on ISS dimensions and photos, the interior sequences allowed more creativity with the exact props and positions being changed to suit the narrative.

Animators, many of whom have spent their careers giving CG characters and objects the illusion of weight, had to throw out everything they'd learned. With the help of some physics lessons, they had understand the implications of zero gravity and zero air resistance. Once something starts moving it won’t slow down. They studied YouTube videos for examples to draw upon.

They rapidly moved from objects to special effects; understanding what fires and explosions would look like in zero gravity. Fortunately for real astronauts there are few references and information about fires in space. The researchers found a match being lit in space on YouTube, but it was very small compared to an on-board fire. However, with some real life practical simulation with special effects artists and their imagination, they scaled it up to generate the resulting blobs of fire floating in the ISS. Similar processes were used to understand the parachute deployment sequence, where models were made to figure out the sequence of events.

There were other details to pay attention to. From the right amount of dust surrounding the Hubble Space Telescope to understanding the orbit of Earth and what parts of it would be on display in each scene. By using 3D a greater sense of the depth of space could be created than 2D could suggest. The CG portions of the film were created in 3D on the computer, while the live-action shots were filmed in 2D then converted to 3D.

So where does the reality stop? Actually the drama and narrative of the story is key. So when the researchers found out that the docking process actually takes 4 minutes, artistic license meant this had to be shortened to avoid losing the tension and boring the audience. When the astronauts needed to lift their arms above their shoulders, they were able to go further than would be possible in a real space suit. And the fire on the ISS had to be more exciting and dramatic that the zero gravity and zero turbulence environment indicated that it would be.

There are scenes in Gravity which all viewers will guess are CG, like the wide shots of the ISS which would be impossible to film. But there are shots which feel as if they were done on a film set with CG added. However, the aim of the film is for you to be awe struck in wonder, not worrying about how the images were shot. The 400 people who worked on special effects of Gravity know that they’ve done a good job when you leave the cinema wondering how they got a film crew into space!

Original material and quotes courtesy of www.framestore.com

Images courtesy of Framestore and Warner Bros. Pictures