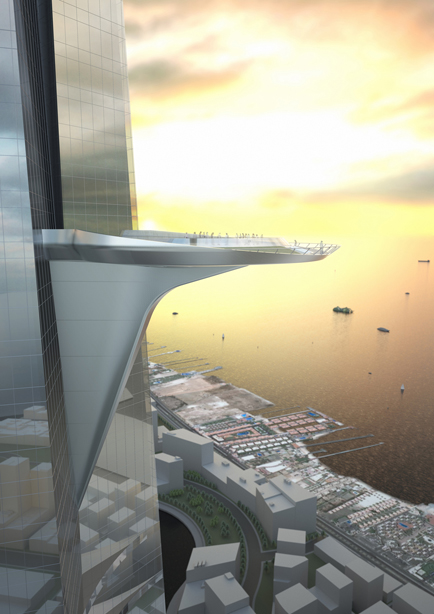

The Kingdom Tower in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia will be the first tower in the world to be more than a kilometre high when completed in 2017 - the tallest man-made structure ever built.

Putting the height into perspective is difficult. The tower will be four times the height of London’s new Shard, Western Europe’s tallest building at 308m. It will be double the height of the Shanghai World Financial Centre at 492m, and almost twice the height of the One World Trade Centre in the US, which is 541m high.

The Middle East is no stranger to bold statements of power and wealth, but the Kingdom Tower is ostentatious compared to even the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, which it will be 173m higher than. The project was created by and is led by reportedly the wealthiest Arab in the Middle East Prince Al-Waleed bin Talal.

At a cost of $1.2bn the Kingdom Tower will have 200 floors, 160 of which will be habitable. It will also host a five star hotel and office space. The company behind its construction, is the Jeddah Economic Company (JEC) is not shy of espousing its grandiose vision. Eng. Talal Al Maiman, executive director, Development and Domestic Investment of JEC, says: “We envision Kingdom Tower as a new iconic marker of Jeddah’s historic importance as the traditional gateway to the holy city of Mecca.

“It will become both an economic engine and a proud symbol of the Kingdom’s economic and cultural stature in the world community. A landmark structure that will greatly increase the value of the hundreds of other properties around it in Kingdom City and indeed throughout North Jeddah.”

Originally planned to be a mile high, the kilometre-high Kingdom Tower will still be the largest structure on Earth when completed in 2017

After the Tower’s initial announcement in 2008 and the award of its design to US firm Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture in 2011, construction started at the site in January 2012.

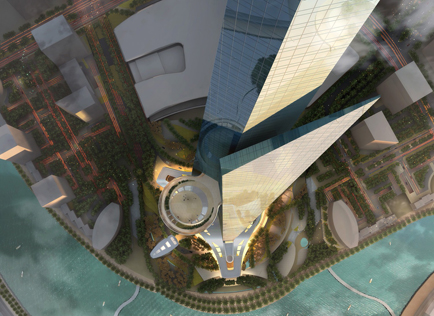

The Kingdom Tower’s core form will be a Y-shape because, say the architects, it offers the highest ratio of exterior wall to internal area and allows for the “three petal” triangular spreading of the base of the tower for stability, without increase the depth of the lease span. The building also has a continuous taper to counter the wind vortices around it.

The structure of the Tower will be concrete walls, coupling beams and reinforced flat plate concrete floor plating. The uninterrupted nature of the walls enables a “jump form system” to be used for constructing each floor. Formwork for the floor slabs will be reused thanks to the repetitive geometry of the Tower.

Recently after a long gap in updates about the project, several announcements have been made relating to the construction - most importantly that the foundations have been completed and that work on the steel structure has started.

Details have also begun to emerge about some of the engineering challenges involved in constructing the Tower. Construction company Saudi Bin Ladin Group has appointed a Beirut-based consultancy, Advanced Construction Technology Services (ACTS), to provide engineering advice and to test the construction materials being used.

According to ACTS, the Tower will use half a million cubic metres of concrete and 80 000 tons of steel. The consultancy is setting up an on-site laboratory to test the quality of the concrete and steel in the build - the massive weight of the building necessitates the use of the highest strength, highest quality concrete. The first job for engineers is to investigate how to pump the concrete to the very high elevations required to build the tower.

Traditionally concrete was mixed and then lifted to the heights required when constructing tall buildings, using buckets and cranes. Since the early 1970s hydraulically powered and controlled pumps have been used, where a ground unit pumps concrete from a hopper up a thin pipe supported by a boom.

Pumping concrete higher and higher is limited by the plastic qualities of the concrete itself and the capability of the equipment to pump at extremely high pressures. It’s likely that engineers will build on the technique used the last time the problem was faced, which was the construction of the Burj Khalifa. For this project, German concrete pump manufacturer devised a high pressure delivery system with a reinforced frame, fitting and valves. The trailer pumps operated for 32 months, sending concrete as high as 606m. The high compressive strength concrete was chilled in the concrete plant during the day and ice instead of water for mixing. The concrete was only poured at night because it was too warm during the day.

The concrete, although a basic problem, is far from the only engineering challenge involved in building a kilometre-high structure. Even the elevator system is a challenge. The Tower will contain 59 elevators, including five double-deck elevators as well as 12 escalators. The plant and equipment used for water, heat, sprinklers and other domestic systems will also have to be engineered to work at the lower air pressures so high up.

Engineers all over the world will be working during the coming years to solve these and other challenges, pushing the limits of engineering to realise the dreams of a single man and shape the future of an entire country.