French software company Dassault Systèmes has shown off the first results of a project to digitally preserve the vehicles and engineering behind the D-Day landings in the run-up to the event's 70th anniversary.

Researchers have taken eight months to digitally recreate iconic vehicles such as the Waco-Glider and the LCVP troop carrier, the boat which released tens of thousands of troops onto the beaches of Normandy on June 4th 1944, as well as the unique Mulberry temporary harbours which were floated in afterwards to unload vital supplies from ships.

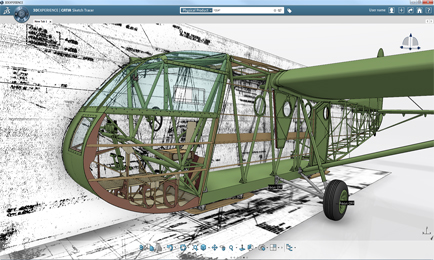

Modern CAD software is being used to preserve the engineering behind D-Day for future generations

Modern CAD software is being used to preserve the engineering behind D-Day for future generations

The results will be used to preserve detailed engineering plans and for virtual reality demonstrations of the Normandy Landings in museums, exhibitions and education.

D-Day is well-known for being the largest seaborne invasion ever and the first step towards Allied victory over Nazi Germany. Numerous films and documentaries of the event have eulogised the heroics of the servicemen involved. However, many innovative designs were also devised by British and American engineers to enable the operation, including some which are still used today, and much of the detailed knowledge of the engineering behind the invasion is at risk of being lost.

Nicolas Serikoff, specialist in charge of Dassault Systèmes' D-Day Project, says: “Many of the records of the innovations and designs have already disappeared. 3D digital mock-ups preserve that industrial memory, so we have initially aimed to develop several of the iconic machines from D-Day. It’s a real tribute to the engineers of D-Day who made it happen.”

Engineers from the Computer Aided Design (CAD) company, whose 3D design and simulation software is widely used in sectors such as automotive and aerospace, had to use a variety of different data sources to digitally recreate the 3D models.

Mehidi Tayoubi, vice president of Global Digital and Experiential, Dassault Systèmes, says: “We noticed very quickly that it was hard to find blueprints and that you lost a lot of detail when they were digitised. So the plan now is for the project to be ongoing and for all the information to be gathered and preserved slowly, as a homage to the engineers that made it possible.”

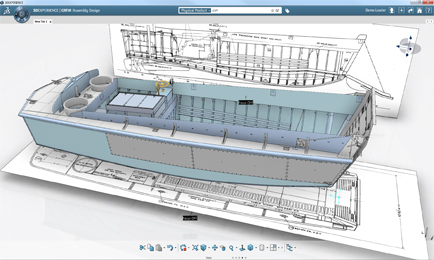

Several of the innovations from the Landings are still used in ships and ports today

Several of the innovations from the Landings are still used in ships and ports today

Today the coast of Normandy is a marine cemetery holding more than 200 wrecks from the invasion, so researchers also used data gathered by underwater archaeological dives, 3D laser scans of replicas, imagery and film, to digitally reassemble the vehicles and harbour.

The first 3D model developed was of the CG-4A Waco-Glider. The aircraft was made of wood and fabric and designed to break up if they hit an obstacle. They were used to covertly insert soldiers behind enemy lines before the beach assault to secure key infrastructure further inland. Travelling at 90 mph they could carry 12 men or a jeep. They were towed across the channel by C47 aircraft and then cut loose. All of the original gliders have since disintegrated.

Dassault engineers rebuilt the glider using its 3D Catia CAD software and the aircraft can now be flown in virtual reality, recreating the flight controls, physics and environmental controls accurately. The 3D model (above) contains fully working 3D representations of the mechanical systems and all of the parts down to the screws and bolts.

The second vehicle digitally recreated down to its nuts and bolts is the Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel (LCVP), a boat made almost entirely of wood to land troops on the beaches. The LCVP is most recently famous for featuring in the opening scenes of the film “Saving Private Ryan”.

More than 15,000 LCVPs were made in New Orleans by Higgins Boat Industries, which based the design on boats used in the Bayou swamps, with additional features including a metal front ramp that opened quickly when they hit the beaches. The hull, rudder and propeller of the LCVP were carefully designed so it could land and manoeuvre in shallow water – the Normandy D-Day beaches have a water depth of just 1m. Serikoff says that 3D models revealed the clever design of a smaller second rudder on the hull which made the boat reversible out of the the shallow water.

The last part of the project was to create a full 3D recreation of the Mulberry B artificial harbour. The Mulberry was devised by engineers as a way of quickly deploying a harbour because all of the existing harbours were heavily occupied. The Mulberry consisted of some 10 miles of 80ft wide steel roads that rested on concrete or steel pontoons and could carry up to a 40 tonne Sherman tank. These roads connected the beach to a floating pier head out at sea where large ships could berth and unload vital supplies. Huge reinforced concrete caissons were laid in a semicircle around the harbour to protect it from the tides and storms.

The pier heads were unique in that they were on vertical legs and could partially lift themselves out of the water when the tide went out. They would then float thanks to cabling and a specially-designed kite-anchor that dug itself deeper into the seabed when the cable was pulled. This meant ships could unload vital supplies using cranes around-the-clock.

The engineers lived on the ships 2km away from shore during the installation of the harbours. Tens of thousands of pieces of Mulberry A and B were floated into place in a matter of days once the beaches were secure. Although the roads were designed to withstand rough seas and twist up to 45 degrees, Mulberry A was wrecked by a terrible storm on the June 19th, resulting in the wrecking of 800 vehicles. Mulberry B at Arromanches survived and subsequently became the world’s busiest port in terms of traffic volume during the war, but has since eroded into the sea.

The virtual reality experience will be used in museums and exhibitions in the future

The virtual reality experience will be used in museums and exhibitions in the future

Mulberry B was recreated using the original plans, pictures and construction manuals from the Royal Engineers Museum in London. The roadways of the Mulberry were designed by Major Alan Beckett of the Royal Engineers. His son, Tim Beckett, is today a consulting engineer in the marine sector and advised on the project. Beckett says: “In several schemes we use the inspiration of Mulberry. We never have the budget or time constraints they had, but nevertheless there are plenty of lessons here for today’s engineers.”

“The recreation shows you just how huge this harbour was. It was the size of Dover harbour and all the essential elements were constructed in just a week.

“There are lots of innovations that are still used today, like floating caissons. Roll-on-roll-off ferries were pioneered here, Jack up pontoons are used widely by contractors nowadays and floating roadways are also still used today.”

A TV documentary airs later this month focussed on the archaeological dives and virtual reality recreation, but in the meantime, the below videos will give you an insight into the project.