Articles

The impressive tunnel-boring machines used by the Crossrail high-frequency rail project use technological concepts developed over almost 200 years.

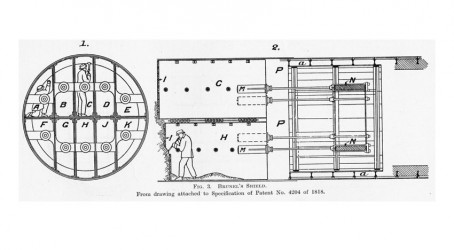

One of these ideas is the shield. During tunnelling, a shield can provide a working area that is protected against the collapse of the walls or ceiling, where no lining or other means of support has yet been erected. The inventor of the first soft-ground tunnelling shield was Marc Isambard Brunel, inspired by his observations of a ship-worm’s ability to tunnel through timber when he worked at Chatham Dockyard.

The shield was first applied during the excavation of the Thames Tunnel. The first tunnel shield was circular, and its function did not include excavation. It was found to be unsuitable for the work, and was used only between 1825 and 1828, when works were temporarily halted because of lack of funding. In 1835, when they resumed, an improved rectangular shelf shield was installed; this was used until the tunnel’s completion in 1843.

Then there is the rock-tunnelling machine. The Belgian Henri-Joseph Maus is recognised as the inventor of the first device of this type. He was commissioned by the King of Sardinia in 1845 to dig the Fréjus Rail Tunnel between France and Italy through the Alps.

The Maus machine consisted of a metal framework that carried percussion drills or chisels. A system of cams, operated by shafts and gears, obtained their power from the main pulley-driven shaft. These cams drew the chisels back against the action of powerful coaxial springs and then released them suddenly, to be flung against the rock face by the reaction of the springs. The entire frame was moved forward during operation by a crank handle. Power was transmitted to the machine by cables and pulleys, driven by turbine wheels, at the tunnel’s entrance.

Maus developed the prototype at the Valdocco arms factory in Turin. The “mountain slicer” drew admiring crowds, but lack of funding meant it was never actually used. The first machine employed to cut a tunnel was Wilson’s Patented Stone-Cutting Machine, used in 1853 to construct the Hoosac Tunnel in Vermont in the US.

Next came the mechanised shield. JD and G Brunton were the first engineers to patent a design for this device in 1876. But John Price’s shield was the first to be applied to a civil project: the Shepherd’s Bush-to-Marble Arch section of London’s Central Line, in 1897. The shield had a cutter head comprising four radiating arms, bearing cutters or scrapers. The arms also carried trough-shaped scoops which collected the loosened material, lifted it and deposited it into a chute from which it was guided into waiting skips.

A more recent development is the earth pressure balance (EPB) machine. Developed by Japanese company Sato Kogyo in 1963, this machine maintains a constant pressure at the face by keeping the rotating cutter frame and screw conveyor filled with earth.

The EPB is one of the two types of tunnel-boring machine being employed on Crossrail. A total of eight devices are being used on the project. They have a diameter of 7.1m, are 148m long and weigh around 1,000 tonnes. Their rotating cutter head loosens the earth, with a screw conveyor moving the earth from the cutter head. Next, a rotating arm places segments to form a ring, and hydraulic cylinders brace themselves on the rings to push the machine forward. A belt conveyor system removes earth from the machine, and pre-cast concrete segments are delivered to the segment feeder to construct the tunnel walls. Finally, conveyors move earth to the tunnel portal.

As well as six EPB devices, suited to driving through clay, Crossrail uses two slurry machines, for moving through the chalk and flint beneath the Thames. The latter differ from EPB machines in three ways. They have a sealed air-locked chamber behind the cutter head; they have inlet pipes; and they use an outlet pipe rather than a conveyor system to remove earth.

Looking at the present machines, it’s remarkable to think that the germ of their development lies in the behaviour of worms.