At Wylfa power station in Wales, one nuclear reactor continues to operate, while the other ceased to generate power only last year. The second reactor at Oldbury in Gloucestershire, also part of the Magnox chain – the world’s oldest commercial reactor fleet – also shut down only in 2012. These monoliths of the British nuclear industry, designed and built in the 1960s, have generated power for much longer than their designers might have envisaged. Keeping them going has required some very up-to-date engineering know-how.

Steven Grant, power and energy director at engineering consultancy Frazer-Nash, has worked on Magnox reactors since the 1990s. In 2003, his team was called on to assess the condition of the 40,000 graphite bricks in each of the four reactors, with a view to helping to demonstrate the safety of their continued operation. “We’d been successful in dealing with difficult, off-the-wall things, and the graphite fell into that category,” he says.

The ageing of these power stations meant increased monitoring was required, he says. “It was something that hadn’t been looked at in the level of detail we were asked for, up until then. There was nothing unusual about that, because Magnox was the first fleet of nuclear power stations in the world. A lot of it was new to us. It was a recognition of the fact that as the station got older we’d probably have to do more to demonstrate that it would continue to be safe.”

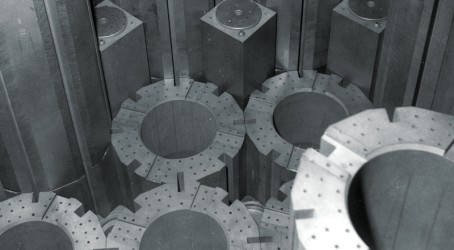

The graphite in the reactor moderates the nuclear reaction, gives structural support, and also directs cooling flow throughout the reactor. The structural integrity of the large structure was analysed by Frazer-Nash using information obtained from material testing of non-irradiated graphite bricks and inspection and monitoring information of the reactor core.

“Graphite is an unusual material,” says Grant. “It changes over time, and depending on where it is in the reactor. And you’re performing an analysis with limited information. It really was a world-first for ‘how do we take this forward?’.”

Another instance of prolonged life is British Energy’s advanced gas-cooled reactors (AGRs). Before its takeover by EDF Energy in 2009, the company worked on extending the life of the fleet. For an individual reactor to operate beyond its design life, the company must continuously demonstrate the safety of the fleet.

Although the AGRs, which began to operate in the mid-1970s, had a design life of 30 years, Hinkley Point B and Hunterston B are now projected to operate until 2023. EDF is planning to extend its other reactors’ lives by an average of seven years, which follows other extensions – provided the safety case for doing so can be made on an ongoing basis. Nigel Houlton, head of lifetime programmes at EDF, says: “We have to maintain ongoing permission to operate, so in the short term there’s a continuous requirement for ourselves to ensure to the regulator that we’re safe on a day-to-day basis.

“Looking at the wider picture, every three years there is a planned outage where we have to obtain agreement to restart, and then every 10 years there is a periodic safety review.”

Certain components and systems in the AGR, such as the boilers and graphite within the reactor pressure vessel, cannot be replaced. Where necessary, these are inspected through remote means, which can involve accessing the pressure vessel. Research and development work at a materials test reactor in the Netherlands will help EDF to confirm its predictions for the ageing of the graphite. The bottom line is that it must be conclusively demonstrated that continued operation is safe. Other parts of the plant, where systems can be replaced, are assessed as well.

The capacity for AGRs to exceed their allotted span would not necessarily have surprised their creators, says Houlton. “I think if you’d gone back to the original designers and said: ‘Do you think these plants could run beyond their scheduled life?’, they would have said ‘yes’. But they would have been unsure how long. The AGRs are unique, so we can’t learn from operational experience elsewhere in the world. We take it step-by-step, and continuously make sure we understand what is going on inside the reactor itself.”

On the motives for prolonging power station life, Houlton says that the takeover of British Energy by EDF acted as a “spur to look more proactively at life extension”. There is no correlation between the tortuous progress of nuclear new-build post-Fukushima and the desire to extend the life of the reactors, he says. “Our strategy is to extend the life of the stations where it is safe and economically viable to do so. Life extension is a standalone objective, and isn’t swayed by what’s happening on new build.”

At Wylfa and Oldbury, the challenges were different because of the age of the reactors, but work by Frazer-Nash has resulted in one reactor continuing to operate today and the extension of the lives of the other three. Some of the knowledge that helped make the safety case was obtained in unusual circumstances, and included speaking to experts in Russia, says Grant.

“We established that the reactors were in good nick, and that perhaps we could extend the life. And the bill for decommissioning is huge. If you can prove that it’s safe, there are big incentives to keep them running.”

At one point, Frazer-Nash had more than 20 engineers on the projects at Wylfa and Oldbury, working with Magnox staff, many of whom had decades of experience in the nuclear industry. “None of us thought that we couldn’t demonstrate that the reactors were safe, although we knew it was a difficult, challenging problem – a multidimensional one, which for the engineer is fantastic,” says Grant.

“It’s pretty special to be keeping nuclear plants operational.”

UAV inspection cuts cost of decommissioning North Sea oil rig

Asset management firm Cyberhawk, which uses remotely operated unmanned vehicles to inspect flare stacks and electricity pylons to help plan maintenance, has carried out what it claims is a world-first inspection of an offshore oil rig using the technology.

Cyberhawk’s remotely operated UAV captured high-definition images of the condition of a derrick on a rig being decommissioned in the North Sea. Using the UAV meant that drilling operations on the rig did not have to

be suspended, thereby saving money. Rig operators are under pressure to reduce the cost of decommissioning, two-thirds of which is funded by the taxpayer. Without Cyberhawk, the alternatives would have been a manned rope or scaffold inspection – both options that require suspension of drilling operations for safety reasons.

“A large part of the decommissioning process involves drilling, and it’s a big cost,” says Cyberhawk co-founder Malcolm Connolly. But even rigs that are being dismantled have to be kept in good condition. Cyberhawk’s analysis enabled repainting work on the derrick to be reduced by almost half. In addition, the results allowed a preservative coating to be applied only to the parts of the derrick that needed it, saving time. The project is said to have saved Shell, the rig’s operator, £4.6 million.

Operators can be more willing to take risks with new technology when decommissioning, says Connolly. “The downsides of trying something new and getting it wrong are greater in production,” he says. “But in decommissioning, there’s perhaps a greater degree of innovation, and a willingness to explore new avenues to cut costs.” The

project was recognised recently by an award from UK Oil and Gas.

The UAV inspection did carry an element of risk. “There were technical unknowns in taking our equipment offshore, including the movement of the platform, magnetic fields generated by the rig, and the wild North Sea elements,” he says. “Working on this in January last year was also a challenge because of the weather: you can get 100ft waves in the winter up there. We did a subsequent inspection of the underdeck, which is about 28m above sea level and had sustained damage from waves below the platform from a storm.”

But a particular difficulty was making the case for the method, says Connolly. “The main challenge was to convince an operator that it was worthwhile to take the risk of introducing this technology offshore.”

The next step will be to try out a similar operation on a production oil rig, he says. Cyberhawk is also working on a project to inspect offshore wind turbine blades. “One of the biggest problems with offshore wind is maintenance,” he says.

Make sure you’re up-to-date on maintenance

This year’s Maintec exhibition will take place on 3-5 March at Birmingham NEC. The meeting-place for the UK’s maintenance, plant and asset management community, the show is now in its 38th year.

The exhibition is intended to provide a snapshot of current developments in technology and business standards for maintenance, which are subject to continual change, say the event organisers. Maintec can provide the opportunity to source the right suppliers to make sure projects can be delivered on time and on budget, they say, in a world in which projects must be ever more “innovative, efficient and productive”. Cost and time pressures are greater than ever in maintenance, so the show provides the chance to source products and services, learn from industry experts, and network with fellow professionals, and discover predictive, preventive and corrective maintenance solutions to reduce downtime and increase efficiency.

A visit to Maintec should provide you with a wealth of information and inspiration that you can’t find elsewhere. You will find the resources you need to ensure your plant, systems and operations are as efficient as possible – saving your organisation time and money, the organisers say. The top five reasons why you should attend, they say, are to:

1. Meet suppliers with cutting-edge solutions to help you boost plant performance, reduce costs, improve safety and ensure industry compliance.

You will discover many innovative solutions to

your challenges.

2. Learn from the industry’s leading experts, uncovering the latest solutions and best practice in the free seminar programme.

3. Build your skills, develop your knowledge and enhance your career prospects through the show’s interactive features.

4. Network with peers who have faced challenges similar to yours.

5. Take the lessons you learn back to your workplace and make a difference to your organisation’s maintenance strategy.