It is also a triumph for 4c Design, the product design and engineering company behind this symbol of the Games.

Robin Smith CEng MIMechE, and Will Mitchell, directors of the Glasgow-based company, are rightly proud of the achievements of their colleagues and associates who designed, researched, crafted and tested the baton. It has been a journey in itself to produce the beautiful elm wood and titanium article, from the tendering process; through stakeholder considerations; and pushing the boundaries of design engineering.

Robin, who is a key member of the Glasgow and South West Scotland Area committee, is committed to sending out the message of creativity and engineering to schoolchildren, and will be delivering an Institution lecture about working on the baton next summer. He is delighted that Institution CEO, Stephen Tetlow, visited 4c Design during his recent trip to Scotland, and had the opportunity to learn more about the article at first hand.

It has been reported that Her Majesty commended the baton design as “extremely clever.” HRH The Duke of Edinburgh, an avid design enthusiast who chaired the Prince Philip Designers Prize for more than 50 years, was intrigued by the intricacies of the puzzle mechanism, which locks in the Queen’s personal message to the Commonwealth.

Robin and Will describe the steps along the way to the momentous Queen’s Baton Relay Launch, held at Buckingham Palace on 9th October, during which the Queen placed her handwritten message to the Commonwealth nations into the baton. It signified the beginning of the baton’s own 190,000 km, 288-day journey to 70 nations and territories, before a final 40-day tour of Scotland takes it to Glasgow’s Celtic Park for the Opening Ceremony of the Games on 23 July 2014.

Will explained: “After winning the tendering process, we focused during our brainstorming sessions on the themes of ‘culture’, ‘message’ and ‘sport’ in working up the designs. The baton needed to be tactile, practical to handle, and to reflect – visually and intrinsically – the culture of Scotland and Glasgow. In that, we focused both on the city’s industrial heritage and in the natural resources of the country. We also wanted the handwritten scroll to be reassuringly visible within the baton.”

Robin said that although Commonwealth Games hosts have, in recent years, invested their batons with up-to-the-minute electronics, the ambition at 4c for Glasgow 2014’s baton was to create something beautiful and practical: “Because 4c is a mechanical design consultancy, we wanted showcase how quality mechanical engineering can still capture the imagination in an increasingly digital age. The Glasgow 2014 baton is unashamedly a ‘mechanical engineers’ baton’ that uses craft techniques, and cutting edge manufacturing. We wanted an object that would inspire people to use the technology they’ve got in their hand (smart photos and cameras) to share images of it, and communicate their interaction with it, all around the world.”

Will and Robin were set on using wood for the handle, and commissioned the GalGael Trust, a local social enterprise company, to make it. The handle was crafted using a boat-building technique called bird-mouthing, traditionally used to make masts for ships, so that it would be light, strong and durable, with a hollow centre. It is made from an elm felled in the grounds of Garrison House on the Isle of Cumbrae – a tribute to Scotland’s natural resources. The handle houses the intricate electronics for the LED which lights the upper portion of the baton, illuminating the handwritten scroll.

They said: “We were keen to use wood, for its purity and practicality. We discussed it with the stakeholders, who feared the wood would deteriorate during the baton’s tour, but we were sure it was the best material for the job.”

To prove it, Robin explained, they rigorously tested the resilience of the wood:

“GalGael made us a new door handle for our office, and we calculated the door was opened up to 200 times a day, over a three-month period. Unwittingly, the postman has been part of the testing exercise! The elm stood up to the use brilliantly – and we also feel that a little wear and tear on the baton would also reflect its incredible travels. We applied only a light oiling to the Queen’s baton, and feel its natural state is best for the job.”

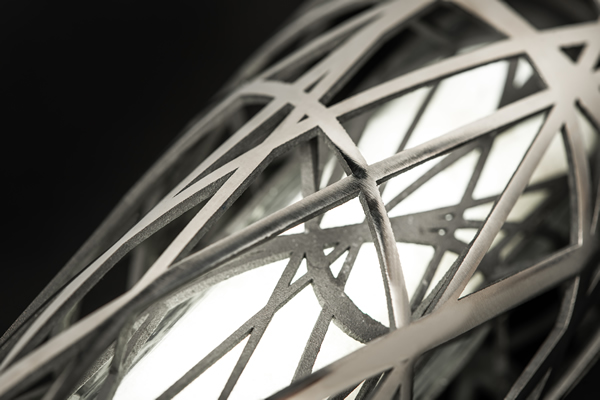

The baton’s upper portion, an intricate lattice structure, is made from pure titanium. Robin set out the inspiration behind this element: “Famous aspects of Glasgow’s industrial heritage, from the landmark cranes of Clydebank to the architecture of Glasgow-born Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the lighthouses of Robert Stevenson, informed the lattice design. Using a CAD Rhino package called Grasshopper, our associate Brian Loudon designed a script that created an interlacing series of circles and ellipses at random heights and angles. The script, which took 3 days to write, then iterated its way through multiple designs in just a few minutes, and very soon we’d identified the one we wanted, which required only minor hand-drawn modifications.”

Titanium was selected as the ideal metal, as it will withstand the corrosive environments of sea air and humidity that the baton will encounter in the South Pacific islands; it is as light as aluminium and as strong as steel.

With 4c’s objective of showcasing cutting-edge mechanical engineering in mind, the process of direct metal laser sintering (DMLS) was selected: it would ‘grow’ rather than ‘cut’ the titanium structure.

Having proudly taken on the unprecedented contract, and successfully created a sample piece, Newbury-based 3T RPD Ltd embarked on creating the baton’s unique latticework. A market leader in additive manufacturing (AM), 3T grew the lattice over a 30-hour period (literally, during a weekend), using the technique of fusing metal powder into a solid part using a focused laser beam. The baton’s lattice section, made up of 4000 layers, has a double structure. The outside was polished (for the equivalent of eight days) while the inner formation largely retains an untreated, satin finish.

Jon Vickers, Metal AM Process Manager at 3T said that every time a customer approaches the company to produce a metal additive manufactured part, the company views it as a new challenge. Build orientation – the way in which a part is placed and supported on the platform during manufacture – influences the build’s success and was a huge consideration; as were the properties of titanium, which is strong, but prone to stressing. Cost management also had to be considered; and it must be remembered that the titanium section was made up of several parts, all with differing requirements.

Jon explained: “The baton is made up of six titanium parts. The build orientation for the main part was a simple decision – it was built ‘upside-down’ with the flat surface on the build plate. The circumference of the top of being larger than that of the bottom, the sides of the baton were significantly self-supporting during the build. The exception was the downward facing areas of the lattice. One concern was to ensure the accuracy of the build so that as the individual strands of the lattice weave upwards as each layer is built, they met perfectly when they were reunited.”

“The collar of the baton required a different approach, to manage the sudden changes in cross section of the piece. The supports were essential to discharge stress, which built up in the metal. The puzzle pieces were built at a different orientation in order to ensure that all build surfaces were consistent.”

Jon confirmed the delight felt at 3T at the success of the baton: “We feel really proud to have been part of the team that produced such a stunning piece. The titanium lattice could not have been built using any other technology and we think the contrast between the highly polished finish of the external strands of the lattice against the ‘raw’ titanium finish on internal strands makes a really visually exciting item. Normally, we produce metal AM parts for F1 cars, the aerospace or medical industries, so it was great to be involved in something so different.”

The handle and the lattice are the manifestations of very different manufacturing processes – as Robin said, there isn’t a computer in sight at GalGael. With minute electronics created for the sophisticated LED which illuminates the Queen’s message, as well as a mechanical puzzle to lock in the precious scroll (more on that later) Robin explained that 4c wanted to create the first baton that actually gifted something to the 70 nations: “Each nation and territory will receive a gemstone of native granite, crafted by Kays of Scotland (famous for making premier curling stones) and a coin embellished by jewellers from Glasgow School of Art.”

Alex Salmond, First Minister for Scotland, was delighted with quality of craftsmanship and the materials chosen, particularly the use of Ailsa Craig granite. He commented: “It’s an absolutely brilliant design. Congratulations to 4c and all involved for creating a beautiful work of art that will leave a permanent legacy of friendship across the Commonwealth.”

One of the most talked-about features of the baton is the mechanical puzzle, inspired by an ancient Japanese puzzle box design, which locks the Queen’s message within and houses the Ailsa Craig granite gemstone. The security of the message was an important factor, and in locking the scroll in, the baton can be freely handled and passed between members of the public.

Robin – and many others – enjoy the code, or ‘safe-cracking’ element of the top slice of the baton: “The mechanism is a four-way sliding set of jaws which hold the stone in place, a bit like a diamond within a setting,” he explained.

“We drew it up in CAD, laser-cut a 2D prototype in Perspex and it worked as a principle. We took that principle and progressed it to a rotary mechanism. The sequence required to release the Queen’s message only needs to be opened one more time, and we don’t want to give away the secret message before July 2014! There’s a hidden locking pin that has to be removed, so there’s no chance of that happening.”

As with other development stages for parts of the baton, such as testing its weight in the hand, and the performance of the wooden handle, the baton goes through a ritual in each of the 70 countries. During this ‘end of day ceremony’ a spring raises the gemstone as the four ‘jaws’ open, presenting the stone to the nation’s dignitary. Robin says there were issues with the force, and particularly with the damping of the spring, when they were prototyping this mechanism.

“It came to me that my IKEA kitchen cupboard door hinges, with their robustly tested soft-close mechanism, operated in precisely the way required by this section of the baton. We replicated, in stainless steel, a mini soft-close hinge which does the job. Why reinvent the wheel?”

In all, Robin calculated, a collective 4,500 hours of conceiving, researching, designing, testing, and finishing was given by those involved with creating and delivering the baton. The beneficial elements of this unique project even go beyond the satisfaction of delivering a beautiful, bespoke object of craftsmanship and engineering.

“The value of teamwork was never more keenly felt than on this job,” he said. “For six months, and a crucial five weeks as we turned the concept into a physical reality, a group of people let the creation of the baton take over their lives. If I was proud of what we had achieved before the baton, the power of this endeavour has consolidated our creativity and unity way beyond that.”

For more information about the Queen’s Baton, including a ‘making of’ film, visit

http://www.4cdesign.co.uk/

To follow the baton on its journey around the Commonwealth

http://www.glasgow2014.com/queens-baton-relay

Images courtesy of Glasgow 2014