The three giant machines are scary and motionless, locked away in a dark warehouse in the Omani port town of Duqm, gathering dust. Weighing more than 1,000 tonnes each, they are drone miners, primed to get their diggers dirty – but it’s not land that they are meant to mine. It’s the bottom of the sea – off the coast of Papua New Guinea (PNG).

If the Toronto-based company Nautilus Minerals has its way, in 2019 these mammoth, remotely-controlled robots will be lowered into PNG’s clear blue waters, some 1,600m below the Bismarck Sea. Nautilus has been trying to dispatch them for years now, with the aim of harvesting copper, gold, and other valuable minerals on the ocean floor. But the start of the controversial Solwara 1 project has been plagued by delays, due to financial disputes with the local government that wants its share of the Canadians’ money, and protests from various environmental groups.

Built a decade ago, the machines have been in Duqm for more than a year. But now, at long last, they are due to make the long sea journey to PNG, where they will undergo their first-ever real ‘wet tests,’ to ensure their controls and cameras work properly underwater.

For Nautilus, the project is about unlocking a cost-effective and sustainable source of metals – crucial as the world’s demand for minerals soars, and with land resources becoming “increasingly stretched,” says the firm’s chief executive Mike Johnston. Only 30% of the world’s metals are on land, and the metal grades on the sea floor are much higher and produce less waste, he adds. But for green activists, it’s a horrible concept; they fear that it will forever disrupt fragile marine ecosystems. Whatever side one takes, with the money to PNG officials now paid in full and all environmental certifications received and signed, it looks like the world’s first deep-sea mining adventure is finally – at long last – about to start.

So, what is down there, on the seabed, that’s so attractive? For starters, it’s the sheer amount of minerals, says Mark Hannington, a geologist at GEOMAR-Helmholtz Center for Ocean Research in Germany. Take the so-called Clarion-Clipperton zone – a 7,240km long stretch between Mexico and Hawaii – where scientists believe that an estimated 30 billion tonnes of nodules can be found on the seafloor. These nodules are golf ball to potato-sized lumps of nickel, cobalt and copper, found deep below the surface, at depths of between 4,000 and 6,000m. It’s “an astronomical number and is probably enough metals, particularly of nickel and cobalt, for decades into the future at current rates of consumption,” says Hannington.

Then there are manganese crusts that contain mainly cobalt, but also vanadium, molybdenum and platinum, found at between 800 and 2,400m under the surface. Finally, there are sulphides – and, he adds, the ridges explored for sulphides so far represent a “tiny fraction” of what exists in the ocean. “There could be up to 600 million tonnes of sulphides beyond those areas, with probably enough copper or zinc to launch a major industry.”

Nautilus wants to be the first to get to these riches. Others have toyed with the idea in the past, as far back as the late 19th century. But because the amount of minable metals was originally overestimated, thanks to low metal prices in the 1980s, and the technological challenges of mining the seabed, many companies abandoned the pursuit. Some firms have used remotely operated vehicles with drills and cutting tools to collect mineral samples from potential mining sites, but that was about it.

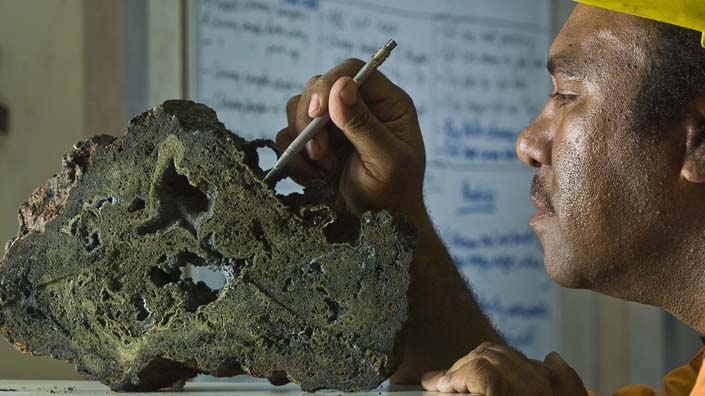

Nautilus has stuck with the idea, though – probably keenly aware of the rapidly growing demand for precious metals used in consumer electronics. The company had to start from scratch and find somebody to build the right equipment; the Canadians contracted UK specialist subsea expert SMD, which developed and built three monstrous mining machines.

They are totally custom-made, of course: the endeavour is without precedent, and thus a big challenge, says SMD’s principal engineer for subsea mining Nick Ridley. The Auxiliary Cutter and the Bulk Cutter will first cut and collect the rock, excavating material by a continuous cutting process – similar to, say, coal mining machines on land. Then their robotic partner, the Collecting Machine, will gather the cut material – sand, gravel, and silt – by drawing it in as seawater slurry with internal pumps, and pushing it through a flexible pipe to the riser and lifting system to a ship above. There’s no ship yet, though – it’s currently being built in China.

Apart from a few tests to determine the best way to pick up the mined product

and study water flow in and around the cracks that the machines are likely to make under high subsea pressure, there have been no major trial runs. When the project finally starts, everything will be new – and so much could go wrong. Nautilus will be the first to discover the challenges, says Ridley.

But these challenges won’t be just about the technology. While Nautilus thinks it’s time to dive head first into the blue waters, many scientists are questioning a gold rush in an ecosystem we know very little about. Administrators, governments, regulatory bodies, scientists and investors are all “sitting in a black hole waiting for information and knowledge and it’s just not coming,” says Hannington. So far, many private projects looking into the potential impact of deep-sea mining have made little progress, and exploratory mining “has been a disaster” – while those who do have some data don’t want to disclose it, he says. Sharing of information is crucial though to create standards and best practice to make deep-sea mining safe and ethical.

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) that governs waters outside of national jurisdiction, where a great deal of the deep-sea mining will take place, will be largely responsible for policing the budding industry.

So far, it has issued 15-year contracts for exploration of polymetallic nodules, polymetallic sulphides and cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts in the deep seabed to 26 contractors – but few are as far advanced as the Canadian firm. One rival, a Japanese consortium led by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Nippon Steel and Sumitomo Metal, is running a pilot mining and lifting ore from the Izena sea hole, just off the southern island of Okinawa. There are an estimated 7.4 million tonnes of nodules in the deposit.

If Nautilus succeeds, many more companies are likely to follow – and ideally by then regulations will be in place. That’s why ISA is busy developing new rules for deep-sea mining, looking at environmental and operational issues. The authority has shared its Regulatory Framework for Mineral Exploitation among the 156 countries under which it operates. Hannington says it will be a long and time-consuming process, before the code for exploitation of minerals is ratified by its member nations – and it’s likely that companies, driven by financial pressures, may start mining before proper legislation is in place.

If that happens, environmentalists fear harm to the ecosystem in the deep sea could be great, and perhaps irreversible.There is “no question”there will be damage, says David Santillo, a marine biologist and senior scientist at Greenpeace Research Laboratories at the University of Exeter, UK. The bigger question for him is how far from the mining operations that damage might be felt. For instance, apart from the direct effect on the organisms living in the mining area, disturbing the sea floor will create plumes of material that could potentially travel great distances across the ocean.

To assess the potential impact of deep-sea mining on marine life and to develop a set of guidelines for the industry, in 2013 the European Union launched a three-year, 12 million project dubbed MIDAS (Managing Impacts of Deep-sea Resource Exploitation). It involved a series of sea trips exploring, among other places, the Lucky Strike region of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge near the Azores islands.

There, researchers studied the potential effects plumes of particles that might arise from mining near hot hydrothermal vents, often rich sources of metals, could have on deep-sea mussels and other creatures.MIDAS scientists also analysed nearly four decades of research into the impact of industrial activity on deep-sea organisms. Recovery of marine life has been “quite sporadic and poor among groups of organisms,”says Philip Weaver, a geologist and managing director of Seascape Consultants in Romsey, UK, which coordinated MIDAS. “It is the sort of ecosystem that struggles to get back to normal again,” he adds, explaining that creatures that live directly on the nodules are unlikely to come back once the minerals are removed. Artificial briquettes made from scrap minerals could be used to try to remedy this, suggests Weaver, although no research into this has been done yet.

MIDAS has come up with a set of guidelines for best practice in the deep-sea mining industry. They include the creation of “preservation and impact reference zones” in areas rich in nodules, to make sure marine life there is not destroyed. The guidelines also outline the importance of minimising any plumes created by mining, and the need for long-term studies to evaluate the impact on the environment. The project’s suggestions for regulations will help to inform decisions made by the UN and ISA.

With MIDAS, Greenpeace and others being loud and clear about potential damage to the marine life, Nautilus and the rest of the companies exploring deep-sea mining are well aware of their concerns. Ridley from SMD says that the machines have been built to limit as

much material being expelled as possible by “optimising the carving system”. A lot of the material will be sucked away rather than dissipated into the environment, he adds – but acknowledges that there will nevertheless be plumes of excavated material around the machines, as well as noise.

Whatever precautions mining companies might take, for some environmentalists they will never be enough, though. Santillo from Greenpeace thinks that we should reuse materials in electronics and create smarter ones, rather than mine even more from the sea.

But our love for computers, smartphones and cars isn’t about to wane, so at some point in the near future deep-sea mining will become part of the “raw materials spectrum,” says Hannginton. Firms like Nautilus will keep pushing forward – the question is whether or not they will do so responsibly.