The designing of the proposed High Speed Two (HS2) rail line is firmly under way. And with 80% of journeys on the new line predicted to start or end in London, its integration into the city’s transport network at its terminus, Euston, will require serious work.

Euston is already the sixth busiest station in the UK, according to the Office of Rail Regulation. So coping with an influx of people could prove tricky without significant improvement. Getting these extra passengers to their final destinations on London’s already overcrowded transport system could prove even more challenging. Passengers could face serious delays accessing the Tube, thereby eating up any time savings made by using the high-speed line.

At least 23,500 people arrive at Euston between 7am and 10am, with almost 30% of these passengers heading to the Victoria and Northern lines’ southbound platforms. Once the London-to-Birmingham high-speed link is up and running, this number is predicted to swell to almost 40,000.

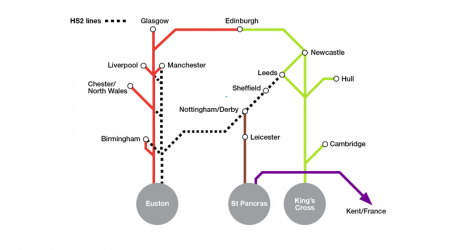

In the second phase of the project, further development of the line will see the high-speed connection serving five extra cities – Nottingham/Derby, Sheffield, Leeds, Newcastle and Edinburgh – and pushing up passenger counts. Once phase two is complete, forecasts suggest more than 55,000 people will arrive at Euston during the three-hour morning peak, as the station attracts a greater share of London-bound passenger traffic.

Peter Moth, senior transport planner at Transport for London (TfL), says: “That is more than twice the current number arriving at Euston. Wait times on the Victoria and Northern lines will be particularly acute. Passengers will have to wait in excess of 30 minutes at the busiest times – that is the equivalent of waiting for 15 trains to pass by before you can board.”

Jim Steer, director of rail industry group Greengauge 21, feels that suggestions of a 30-minute delay at Euston as a result of HS2 are “misleading”. “If you simply put the projected growth of demand at Euston on the use of the Tube and assume that nothing is done to address it, then you would get lengthy delays at Euston, even without HS2,” he says. He argues that plenty of plans are afoot to increase Tube capacity.

Steer adds that analysis by HS2 suggests that the new line will add 2% to the number of passengers at Euston Underground station. “It makes a marginal difference to the level of congestion. But in general, there is going to be a problem of enhancing capacity on the network.”

Whatever the figures, TfL is aware that the social and financial case for HS2 could be eroded unless the high-speed line is integrated into London’s transport network as seamlessly as possible. High Speed Two, the company established by the government to first consider and now develop the line, agrees. In April it began funding a small team of TfL staff to work with it in its London headquarters on the route and station design, and connectivity. Moth is part of High Speed Two’s TfL team, and says the organisation is keen to engage with the issues. “The sooner they get us on their side and inputting into their designs, the better for them.”

TfL should play an important role in making HS2 work. Several key aspects of the high-speed railway’s remit fall within the boundaries of London: the links to Crossrail, Heathrow, and HS1 services for Kent and the Channel Tunnel. But the amount of influence TfL will have over the final designs of the two London stations on the route remains undecided.

Rupert Walker, head of high-speed rail development at Network Rail, says: “It isn’t just about rail connectivity. We need to consider how people will travel to the train and how they travel onwards – other rail, bus or car. The transport integration needs to be carefully planned.”

As well as helping to address the challenges that HS2 will bring for the London network, TfL needs to keep one eye on the growth of the city in the years preceding HS2’s opening and beyond it. By 2030, London’s population is predicted to swell by 1.2 million.

IMechE former president Professor Roderick Smith, chairman of the Future Railway Research Centre at Imperial College London, says that there are issues with the long-term adequacy of the Tube network in London. “If you are taking a 20- to 30-year view, it needs strengthening. That is difficult because it is expensive and potentially disruptive. But at some stage, we’ve got to bite the bullet.” He adds that HS2 could be the catalyst to set things in motion.

At Euston, one plan to improve the connectivity by merging two Tube stations has already been approved by High Speed Two. To accommodate the new link at Euston, the railway track level needs to be lowered. This means the existing Underground concourse will have to be demolished, and a new one built deeper underground. Ideally, the new concourse will be larger than the existing one and have several access points to the HS2 platforms.

Realising these plans will bring Euston Square Underground – a short walk overground from Euston – within 50m of Euston Underground. A new passageway bridging this gap will merge Euston and Euston Square into the same station, and give arriving passengers a choice of five Tube lines.

The Metropolitan, Circle and Hammersmith and City lines will suddenly become accessible, as well as the Northern and Victoria lines. TfL analysis suggests the merger will increase interchanges between the two stations fivefold, and contribute to crowd reductions of 3% on the Victoria line and

5% on the Northern line Bank branch platforms.

Looking further ahead, TfL is encouraging High Speed Two to incorporate a station box for Crossrail Two into the redesign of Euston. Crossrail Two, often referred to as the Chelsea-Hackney line, is an unfunded and uncommitted transport project that, at the earliest, could open in the mid-2030s. Its route has been protected from conflicting development by the government since 1991, and currently runs from Wimbledon in south-west London to Epping in Essex via Kings Cross.

TfL is working on plans to submit to the Department for Transport to amend the safeguarded route so that it could pick up passengers at Euston, too. These plans suggest that the Crossrail Two route would include a double-ended station serving Euston and St Pancras.

Analysis suggests that this amendment could take up to 8,000 passengers off the Victoria line, making wait times for the service at Euston the same as those expected in 2033 if HS2 is not built. Moth adds: “It makes sense to make that provision in the initial station rebuild, rather than going back a couple of years later and digging up Euston.”

Several other measures to help reduce overcrowding on the Northern and Victoria lines are being considered, says Steer. These include extending the Docklands Light Railway from Bank to Euston, and increasing the frequency of services on the Victoria and Northern lines.

On the Northern line, this increase could be achieved by separating the operation of the line’s two limbs. The branches come together at an antiquated junction in Camden Town that causes a bottleneck. By separating them, the throughput of trains on each line could be increased by 50%.

Moth says that overcrowding at Euston could be further reduced by cutting the number of trains that run into the station on the West Coast Main Line (WCML). London Midland trains terminate at Euston from the WCML. But by tinkering with the tracks at Old Oak Common, where the rails of the Great Western Main Line (GWML) are just 200-300m from the WCML, some services could be diverted into Paddington. “It wouldn’t be all London Midland services – just the proportion from Milton Keynes inwards,” he says.

TfL analysis suggests this diversion could keep as many as 10,000 passengers away from Euston during the three-hour morning peak. “This marries up nicely to the initial 10,000 passengers that HS2 phase one is forecast to bring to Euston,” adds Moth. But the scheme will do little to dent the number of extra passengers predicted for Euston once phase two of the high-speed line is complete.

As well as reducing Euston’s footfall, the scheme could improve connectivity across London for passengers onboard by linking with Crossrail. Fourteen Crossrail trains from east and central London are scheduled to terminate at Paddington per hour. TfL believes that eight of these could be extended up the WCML. It is an idea that Network Rail supports.

Steer says that this scheme would bring a lot of benefits and should be progressed. “It’s got a good business case, and it’s not hugely expensive.”

Directing trains to Paddington could mean two or three fewer platforms are needed at Euston, thereby reducing the footprint of the new station. But Moth says it’s too early to say for sure at this stage. High Speed Two says the link would not reduce the size of the station.

Another area where the two organisations have differing views is how best to use the station at Old Oak Common. Under High Speed Two’s current plans, this is an interchange-only station that simply provides a link to Crossrail and the GWML for Heathrow.

But TfL believes confining the station’s role in this way represents a missed opportunity. “TfL feels that a lot more is needed in terms of local rail and highway access,” says Moth. “A number of railway lines that pass close to the site are not in the proposals to stop there.”

Connecting the north and west London Lines to Old Oak Common could open up HS2 to a large swathe of south-west and north-west London. The service to Old Oak Common by these lines could also bring five airports within an hour of the station: Gatwick, Heathrow, City, Birmingham and, potentially, Luton.

Steer says that connecting the west and north London lines to Old Oak Common would be complex and likely to be expensive. “These are good ideas, but the important question really is whether TfL is interested in developing and promoting them, because there is no reason why High Speed Two would do so. They certainly wouldn’t say it was needed to get the benefits of HS2.”

Walker adds that Network Rail sees great potential for Old Oak Common. “As HS2 is a new railway, the opportunity to create new transport hubs is fantastic. Creating a new station gives opportunities for redevelopment and regeneration, which will bring benefits beyond

the simple provision of a new transport system.”

Moth and his colleagues have four months to convince High Speed Two of the plan’s merits before the hybrid bill is submitted to parliament in October. It is not yet clear whether the costs of a better connected Old Oak Common station would be covered by HS2’s original £32 billion budget. “Who pays for it, and how

it is delivered, can be sorted later,” he says.

Smith says that ultimate decisions on many issues are a long way off, and that the debate may shift as things develop and political complexions change. “The overall imperatives are to provide the extra capacity to move people around comfortably. That over-rides everything else,” he adds.