Teams working on such disparate products might have an unexpected number of shared challenges – yet, until now, there was no unified strategy to help solve them. The National Materials Innovation Strategy, launched by the Henry Royce Institute in parliament on 9 January, aims to change that.

We spoke to CEO Professor David Knowles about the opportunities the new strategy could bring.

Where did the new strategy come from and what are its aims?

I've been at Royce now for six years as the CEO. One of the things that really struck me not long after arriving was that we had a national institute around materials and materials innovation, but we didn't have a national strategy.

One of the things that we did quite early on was we started to look at roadmapping exercises around some of the big challenges: “What do we need for a hydrogen economy?” or “What do we need if we're going to transform into a new renewable sector, or the next generation of healthcare?”

As we worked through those, it became clear that we needed to do this in a slightly broader, more cohesive way, because materials has been historically siloed. So the strategy was born out of the fact that we needed to go on the front foot and actually say “How do we develop a more cohesive [materials] community across the UK, and how do we draw together the synergies that we've got, recognise and celebrate the differences?”

Whatever the flavour of government, materials is at the root of the big national imperatives – things like net zero, a healthy nation – but it's often everyone's second best friend. We don't get in the spotlight very much. So it was really to celebrate it and say “How can we turbocharge it?”

The Henry Royce Institute, the UK’s national institute for advanced materials research and innovation

Why is materials innovation so important to sustainability?

Let's start with the big volume producers. The steel industry, the cement industry, they're the lifeblood of western economies. They are also our biggest CO2 (carbon dioxide) producers.

There are fantastic opportunities that we can take on board in terms of reducing the CO2 footprint. It's quite hard to eliminate it, but to dramatically reduce those carbon-intensive areas would have massive impacts for the UK.

There are innovations out there, but they're not really progressing at the pace that they could or should progress. There are some really interesting blockers that we've identified. A really good example is in the built environment, one of the blockers has been insurance – which sounds bizarre, but bringing a new material into the built environment brings insurance risk because of things that have happened previously, such as Grenfell and issues with reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (RAAC). That's something we can work with government on. We can also start to build a bridge to the new regulatory innovative office.

So that's one extreme. If we then move to the other extreme, you've got things like renewables. We could talk about hydrogen – if we look at latest-generation electrolysers, they use iridium as a catalyst. Iridium is a byproduct of platinum production, it's that rare, and we will not produce the hydrogen at the scale that we're talking about unless we really improve our catalysts and utilisation of such elements.

That's not just about the chemistry – that's also about how you manufacture those materials. How do you get the really good surface areas? How do you make them really active? Even right down at that atomic and micro scale, there's great opportunities around materials innovation to support that net zero agenda.

The point of all this is: the materials innovation is the start of it.

And if you get it right at the start, it makes the whole process easier and faster.

Speed is one of the things that comes through a lot in the strategy. Things like digital transformation are really key in that respect.

Growth is one of the big topics in the news at the moment – could materials innovation help the government meet its goals?

We did an economic analysis to understand what the contribution was. If you look at material-specific roles, it's just under £4.5bn contribution, just over 50,000 people. Then you start to amplify – practically everyone is manufacturing with the materials and, if you consider the added value, you’ve got a factor of 10 on that £4.5bn contribution to our economy.

It doesn't take a rocket scientist to see that if we've got more innovations coming through in materials, that leads to more products, more applications. As we're looking forward with the Industrial Strategy, one of the key aims is advanced manufacturing. But you've also got defence, which relies a lot on manufacturing. You've got energy, which relies a lot on manufacturing.

We are in a fantastic place to say “This is the bedrock for the Industrial Strategy. Everything builds on this.”

What material development techniques will be particularly important in the next 10 years?

There's two key things that have come out in the strategy, which we think will really turbocharge the economy. One is ‘sustainable by design’. That's something that really cuts across everything. Everyone now realises that there are concerns around resilience in supply. Being able to recover key materials and key elements is absolutely critical, but the impact on the environment is also a key dimension.

The problem the industry is facing, in many ways, is there are no good or consistent measures of sustainability. There's lots of different databases, lots of different people and different techniques looking at different aspects. It isn't really a level playing field, so it's very hard to ‘compare apples with apples’. So [we need to develop] the right skillsets and databases and knowledge about how that feeds through and how we really measure sustainability, right through to the manufactured product.

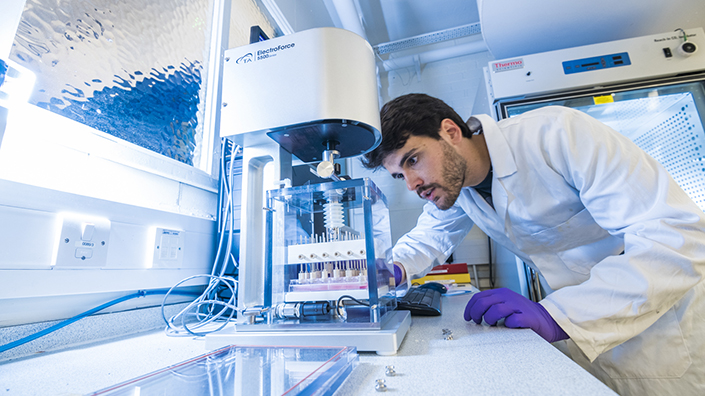

A researcher at the Henry Royce Institute

The other one is digital – we're calling it ‘material 4.0’. From materials discovery and informatics and AI and databases, right through to sensors, Internet of Things, optimising manufacturing routes, digital fingerprints, traceability of materials as they move through, particularly critical materials.

We see that as a key enabler, probably the most important. When we think about how we're going to bind our community together, what binds somebody working in bioelectronics with somebody working in the steel industry? It's going to be a common national framework – material 4.0 is at the centre of that.

Developing materials 4.0 includes a number of facets. One is the skills, people understanding and getting that capability. But another one will be developing common languages, common platforms about how we describe things, which don’t exist at the moment. That's something we have to do at a national level. If it happens in silos, it will stay in silos.

Will all sectors benefit from material 4.0?

It means different things to different organisations. If you're in the large volume industry, let's say the steel industry, traditionally you might be focused more towards efficiencies and optimising process. If you're in early-stage discovery of catalysts, you're looking at high throughput testing, lots of different chemistries etc, and how you may link that with robotic laboratories or something like that. But there's a huge amount of middle ground.

A lot of people just think “We'll throw artificial intelligence at it, and robotics, and it will solve it all.” There's this idea that you can do everything in the minutiae. The real challenge is knowing where to focus and when you need to simplify. Ultimately, things have to move to scale up for manufacture, and the data opportunities and questions keep expanding – it is a tough area, but key to the UK’s success.

Are there any specific materials, innovations or development methods that are going to be particularly important?

I'm going to be a bit cheeky. One of the things we've tried to avoid in the strategy is calling out the ‘next generation of materials’, because what we've tried to do is focus more on the solutions.

I could sit here and talk to you about “Isn't it fantastic, what we can do with next-generation graphene, or metamaterials” – there is always a new flavour of the month.

But I think that the real exciting opportunities are when you start to look at it the other way around, and say [for example] “What are the challenges around health?” When you start to think about personal medicine, you start to think about being able to make bespoke materials – not just the material, but the whole product.

It's the same when you move to areas like quantum, for instance. The opportunities are endless there. A material is interesting from an engineering perspective, because engineers focus on systems and quantum is where a plethora of materials systems come together. So ‘materials for quantum’, rather than ‘quantum materials’, and all the challenges around cryogenics etc, are really exciting and interesting.

I also think the stuff you may think is boring is really interesting. How do you close the cycle on steel? At the moment, we export 90% of our steel to Turkey as scrap. There's lots of interesting innovation in terms of how we close the loop on those really important high-volume materials, particularly as we move to electric arc furnaces.

What would the risks have been if this strategy hadn’t been developed and published?

The main risk is lack of focus. There is investment in materials but often it’s not direct, so it sits in the background. You would have seen that sort of continual, slow development of materials.

There's two really clear things that would be lacking. One would be drawing the community together – that transformation will come from digital. There's an opportunity for us to do something bold at a national level, which really draws the community together and will be transformational in the next five to 10 years.

That, in turn, should unlock investment. Where we've identified those opportunities – whether it's materials for energy, materials for health, plastics packaging – translational routes into market for those opportunities will draw inward investment to support the work, which will lead to more innovation. So it should become a virtuous circle.

I don't think any of those things would happen unless we really drive a strategy. Otherwise it would be the status quo. Why would anyone come and invest more? Why would we expect a common approach to digital to evolve?

Will we have a better chance of solving these big challenges thanks to the strategy?

I'm very positive about it, we're having some really excellent discussions with government. The speech Patrick Vallance gave at the strategy launch really spoke to the importance of materials, and talked about how important it was to invest in the fundamental research, but also to really drive that translational research.

Obviously we're in the midst of quite a change of government. We are looking at the Industrial Strategy – that's really refreshing, to look at things in a new way – but we also recognise that it's not like there are huge budgets around.

Work at the Henry Royce Institute

But this is about driving a trajectory and saying “Where do we want to be in five to 10 years’ time? What's the direction we're going in, and do we see materials as a really important part of our economy?” I think the answer to that is yes. What we need to do is implement the processes that allow that to flourish, rather than go in the opposite direction of either treading water or actually losing place against our competitors.

So I'm upbeat. There’s a lot to do, a lot of discussions to be had. One of the challenges that remains is that materials fits into lots of different parts of government: the Department for Business and Trade, Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, Department for Energy Security and Net Zero. Even transport, Defra (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs). So it's bringing a cohesive view to that, and getting us to a central government perspective, getting them all on board.

Of course, the other big part will be a partnership between industry and government. Industry wants to get on board, these opportunities are commercial opportunities in many cases, but they know they can't realise them individually. It's got to be all-in.

Keeping momentum, I think, is probably going to be our challenge in the very short term. Hopefully that will build as we move into the summer, but we’ve got to keep our foot to the pedal, so to speak.

Want the best engineering stories delivered straight to your inbox? The Professional Engineering newsletter gives you vital updates on the most cutting-edge engineering and exciting new job opportunities. To sign up, click here.

Content published by Professional Engineering does not necessarily represent the views of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers.