There are no secret handshakes in the Whitworth Society and nobody calls its president, Howard Stone, “Captain, my captain”.

“But this is pretty cool,” Stone says, fishing around in his bag.

With the grin of a magician about to impress, he pulls out a small wooden box. It’s the kind of box you’d expect to find at your grandfather’s house… and this one, it turns out, was made not long after the First World War. Inside it lies a chunky bronze medal, passed down to each new Whitworth president. Every award holder who completes the Whitworth Scholarship receives a similar medal, bearing the face of Sir Joseph Whitworth.

“This dazzles people,” Stone jokes, adding that, unlike some less-exclusive societies, there are only about 320 living Whitworth Scholars. His own medal, received in 2002, is at home.

A crafty mechanism, which Sir Joseph would no doubt have enjoyed, releases the heavy, coin-like medal from its chain. On the back are depictions of some of his greatest contributions to engineering: a machine that, for the first time, allowed engineers to measure a millionth of an inch (decades before the world’s first telephone call was made) and three surface plates which, once compared, achieve a perfect flat surface.

Whitworth, a Victorian mechanical engineer genius, also perfected standardised/interchangeable screw threads and revolutionised the manufacturing of rifles in the 19th century. But it was a letter Sir Joseph wrote on 18 March 1868, to the then Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, that would empower young engineers for the next 150 years and earn him a nomination as our latest Engineering Hero.

The nomination comes from Stone, a mechanical engineer by training and a fellow of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. Since Whitworth died in 1887, around the time the first car was being invented, it fell to Stone to channel the man who has occupied much of his time and a great deal of his thoughts. A man he turns to when tough decisions must be made. “What would Sir Joseph do?” Stone likes to say.

Whitworth Society president Howard Stone thinks that if Sir Joseph were alive today he’d be working to raise the profile of engineering (Credit: David Eaves)

Joseph Whitworth was born in Stockport, Cheshire, shortly before Christmas in 1803. By the time he was 14, he was working as an apprentice at his uncle’s cotton-spinning mill in Derbyshire. Four years later, he was the manager.

Full of energy and ideas, Whitworth moved first to Manchester and then to London, working in the workshops of the legendary engineers Henry Maudslay and Joseph Clement. A decade later, obsessed with the precision of his mentors, he broke away to set up his own business back in Manchester. The sign outside read: “Joseph Whitworth, Tool-Maker from London”.

This was the era of the railway, and demand for machine tools was growing. Others were making them for their own factories, but few, if any, were selling them. Whitworth found a gap in the market and, as the Whitworth Register notes, “combined great business ability with engineering genius”.

His inventions had started back in London, when Whitworth set up a new way to produce a true flat plane through hand-scraping and matching instead of grinding. While running his company, he standardised screw threads by averaging out the most commonly used sizes, killing the idea that each nut and bolt had to be engineered as a pair.

He also sent measuring machines on a quantum leap of evolution and worked with the War Office to produce rifles and to improve the accuracy of others by tweaking the rotation of the bullets. The Whitworth rifle was so accurate that some consider it to be the earliest example of a sniper rifle. Whitworth filed dozens of patents, developed his own system of standard gauges, raked in the awards and experimented with horse-drawn street sweepers.

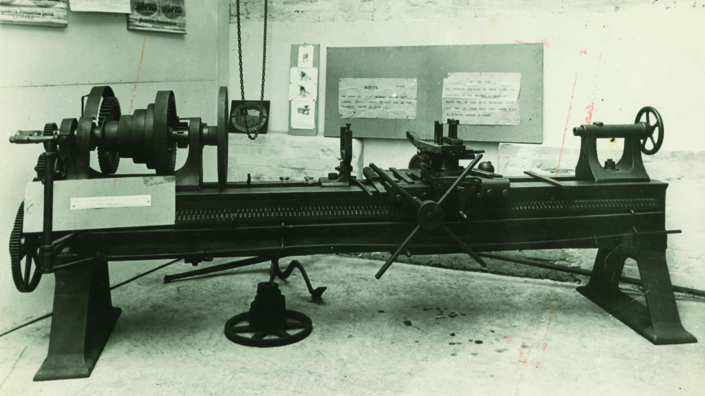

A lathe produced by Whitworth in 1880 (Credit: IMechE)

In 1856, he became president of the IMechE, a position he would return to in 1866.

His factory swelled and eventually employed more than 1,000 workers. His creations were exported to France and South America.

According to the Whitworth Society, Sir Joseph is not as well known as some of his contemporaries because he stayed away from major engineering projects, such as railways, choosing instead to produce the tools that “made these developments possible”.

“His contributions are as important today as they were in his own lifetime,” the society states on its website.

Much like Apple co-founder Steve Jobs, Sir Joseph was renowned for perfecting existing ideas and, again like Jobs, could be a “harsh” and “difficult” man, intolerant of imperfection.

Engineers of the future

By 1868, Sir Joseph had decided to set up a scholarship for the engineers of the future. He was convinced that true success required an engineer to get some hands-on experience (such as an apprenticeship) and to follow it up with academic endeavour, which would unlock the powerful connection between the theoretical and the practical.

In his letter to the Prime Minister, Whitworth promised to fund an initial group of 30 scholars with the aim of bringing “science and industry into closer relation with each other”. He offered £100,000 to get things started. The government accepted and the Whitworth Scholarship was born, to be followed by the creation of the Whitworth Society in 1923. Sir Joseph died well before that in 1887, at the age of 84, but not before discovering some new interests in agriculture and landscape gardening. In his will, he left £500,000 to various education and charity projects.

Stone says the requirements to apply for the Whitworth Scholarship – which has been awarded to nearly 2,500 people – have remained straightforward. Back in Whitworth’s day, applicants had to be “of sound bodily constitution and of good character”. Nowadays, what Stone looks for is a spark. He asks himself whether this is someone he would enjoy having a dinner conversation with. The society doesn’t insist on perfect grades and considers past failures to be building blocks.

In today’s terms, the scholarship can be worth up to £25,000. In return, scholars become brand ambassadors. The real beauty, Stone explains, lies in the Whitworth network, which opens up to those who’ve earned the medal.

Stone once spent a year-and-a-half working in the US, based in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Amazingly, he managed to find a Whitworth Scholar who lived nearby and could show him around. A nine-month project in Dubai came about because of some insight into power stations he obtained during an annual summer meeting organised by the then society president. These regular visits, organised by the society’s presidents, range from car factories to laboratories working on military signal-jamming devices.

Stone says Whitworth Scholars include professors, business leaders and inventors. From nuclear submarines to hovercraft, from satellites to high-speed rail, they have touched every corner of the industry and academia, with 17 fellows of the Royal Society also being scholars.

"Very headstrong"

In some ways, Stone’s career echoes that of Sir Joseph. Stone too worked as a toolmaker and served as a technical apprentice. With his practical experience, he pursued an engineering doctorate and then an MBA. And, like Whitworth, he now directs businesses, Ecolite and DAL-Finance, with fellow shareholders. Stone says he nominated Sir Joseph as an Engineering Hero because he “did more than one thing” and gave so much back to the profession.

“I imagine him being very headstrong,” says Stone. “It gives you energy. There are so many people who don’t make decisions… who bumble along. The ultimate engineer takes the practical, takes the theory and says to the world: ‘this is the best thread. This is the best way to measure something. This is the right thing for us to do as a nation’.”

Another Whitworth Scholar and mechanical engineering graduate, Rachael Hoyle, says Sir Joseph realised the power of pushing someone with practical experience into an area of academic innovation. She believes the scholarship brings people together from across the industry and creates an opportunity for them to develop common values.

“During his career he learnt a set of core skills and developed himself and his business around those skills,” says Hoyle. “He found practical applications for his innovation to make the world a better place. If we apply those values across our engineering community, that can only be a good thing.”

The society’s Karl Dearn says Whitworth was “a fantastic mechanical engineer” who was “technically brilliant but also practically creative”.

Dearn quotes one of Whitworth’s obituaries, which says: “His fame is written in iron and steel, and the daily practice of Whitworth’s men and women.”

On the cusp of a revolution

So what would Sir Joseph say about the state of engineering in Britain today and the skills gap that exists?

Stone believes Whitworth’s solutions would include pushing scholarships even harder, trying to raise the profile of engineering and making it a profession that more young people aspire to join. He thinks Sir Joseph would have supported the government’s plans to boost science, including Theresa May’s promise to invest £2bn a year by 2020, but may have been concerned by attempts to fast-track engineering degrees. Whitworth would also have focused on the standard of education being provided in schools.

A Whitworth medal and presidential invitation from 1857 (Credit: IMechE)

“It’s a fantastic time to be an engineer in the UK and I think Whitworth would agree,” says Dearn. “I think we are on the cusp of a revolution similar to what he saw during his lifetime. The landscape and boundaries between traditional engineering disciplines are blurring, but I think he would have relished the opportunity to solve some of these global engineering challenges.”

Stone says Whitworth’s message to young engineers would be: “Learn the practical first… you can understand the theory better once you have experience.”

Hoyle thinks the message would ring along the lines of: “Develop your skills and knowledge, look beyond the problem and challenge the norm”.

Dearn reckons Whitworth would continue to inspire: “He would congratulate them on a fine career choice and encourage them to apply for one of his scholarships.”

All new Whitworth medals are still individually crafted for scholars by the Royal Mint. Engineering has come a long way and medals can now be 3D printed with the kind of accuracy that Maudslay and Whitworth could only have dreamed of. But perhaps the real value of the medals is not to dazzle, but to remind those who wear them of the engineers who came before, the importance of innovation and the power of a legacy.

For the next group of aspiring scholars, the journey will begin in August, when shortlisted candidates will be interviewed. The next batch of medals is waiting.

Content published by Professional Engineering does not necessarily represent the views of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers.