The latter obviously came out trumps owing to its links with London and preferable location, with Hereford being right on the border of Wales.

Now, all these centuries later, this medieval city is finally fighting back with the help of the New Model Institute for Technology and Engineering (NMITE). ‘New model’ because its ambition is to break the mould of current engineering higher-education provision with a curriculum that focuses on learning by doing. Its students will undertake real-world engineering challenges.

Once NMITE’s validation process is complete, it hopes to swing open its doors to aspiring engineers with the aim of helping to plug the skills gap by adding 5,000 engineers to the market by 2032.

However, NMITE wasn’t always destined to specialise in engineering. Ten years ago, when the nub of the idea was first discussed, the mission of the founding trustees together with local MPs was to revitalise the city by not only bringing in young people – the average age of citizens in Herefordshire is 43 – but to also have the city act as a campus with various sites located across it all within walking distance.

Realising that funding from government would only be granted if their higher education institution was vocational, it didn’t take long for them to strike on the idea of engineering. UK industry is crying out for more engineering graduates but it needs them to have the right skills to hit the ground running.

“Engineering is vocational. A student should be able to go through an engineering programme and by the end be an engineer, not be a better student,” says Professor Elena Rodriguez-Falcon, CEO of NMITE.

“An argument from industry is that, when they employ graduates, they then have to train them through a graduate scheme. Talking to various businesses, this may be why degree apprenticeships have come about. I think that might be unfair but there is truth in it,” she adds.

Inspiration from Boston

NMITE’s founders decided that, instead of offering an engineering curriculum that arguably doesn’t deliver work-ready graduates, they should research models that would. A key inspiration came from Olin College near Boston, Massachusetts, which is a small engineering school set up in 1997 to disrupt education through a project-based curriculum.

With the government happy with this ‘new model’, it granted the project £23m in January 2018 to enable it to start putting the building blocks in place. One of these blocks was to put someone at the helm of its academic vision and it looked no further than Rodriguez-Falcon, who at that point was professor of enterprise and engineering education at the University of Sheffield and was widely regarded for her innovative project-based courses. “Having essentially a blank piece of paper with the opportunity to experiment, to develop, to test new approaches, it’s just so exciting. Who could say no to this?” she says.

Mexican roots

Born in Mexico, Rodriguez-Falcon initially did a master’s degree in mechanical engineering at the Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. Following a few years working in industry in Mexico she decided to study a master’s in mechanical engineering and industrial management at Sheffield Hallam University. Arriving in Sheffield in 2000, her aim was to use her MBA to further her career prospects when she went back home two years later.

However, in 2001, when Sheffield University’s Faculty of Engineering advertised for a mechanical engineer with a business background to help design a new course around business and enterprise, she decided to apply.

She explains: “Having got the job and finding myself teaching business planning I thought that, as it’s just a one-year project, I might as well try something different. Rather than lecturing these final-year mechanical engineering students, with consent from a family who had a six-year-old son born with quadriplegic cerebral palsy, they became our ‘customer’ for the module. The students then had to use their engineering skills to make this boy’s life better. The caveat was that the solution had to be financially viable and marketable and there had to be a business plan at the end.”

Following the success of this module, she was asked to stay on at the university and her problem-based learning methodology that challenged students to develop solutions with real-world stakeholders gained her awards and recognition as an education innovator.

Rodriguez-Falcon says launching a new university is no easy task

“Yes, I received awards but for me it was just common sense. Engineering is about solving problems, so surely if you go about solving a problem you should be able to learn something. And if you then solve more problems again and again then you inevitably become a better problem solver and it will equip you with the skills that will hopefully make you a better engineer.

“It became my life mission to help my students become true engineers by the time they graduated,” she says.

Arriving in Hereford in January 2018, Rodriguez-Falcon was raring to go but soon realised that it wouldn’t be go for at least a couple more years. With NMITE still going through the validation process Rodriguez-Falcon is reticent to talk about timelines but does reveal that “we are well along in the process and nearly there”.

Once it is validated, NMITE can start offering its proposed three-year (46 weeks) MEng in Integrated Engineering programme. Integrated in that engineering will be taught as an integrated whole, as opposed to being divided into traditional tracks like mechanical, civil and electronic, and will also integrate with disciplines beyond engineering, such as humanities, business and the arts. The thinking behind this is that it will equip students with a broad range of knowledge needed to better solve problems in a range of contexts.

The programme also won’t be taught through lectures and tested through exams. Rather, students will tackle real-world challenges as part of a range of four-week ‘sprints’ where they will work collaboratively in small teams. This will be supported by seminars and tutorials. Their portfolios will then show whether they have acquired the skills needed to pass.

Super exciting

As these challenges will be set by real-world organisations, NMITE has spent time getting industrial and community partners on board with its new model. “For this model to work, the contributions of industry via partners is crucial as we need to have a huge bank of partners willing to say that they have a project for the students. We have spoken to 200 different companies and all but one have said that it’s super exciting,” says Rodriguez-Falcon.

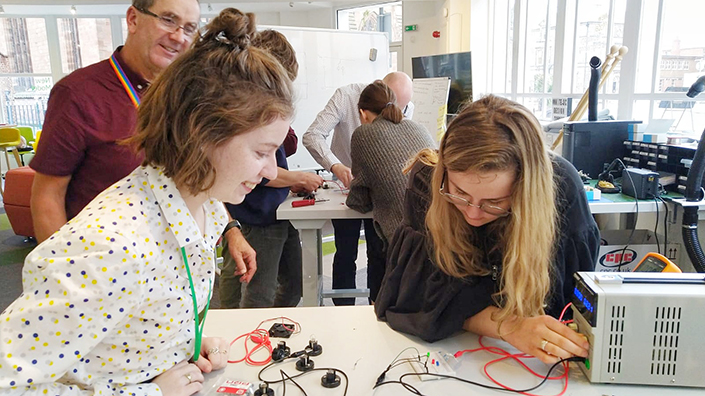

While NMITE can’t yet teach students, it has for the past year worked with university-aged people to help advise and give feedback. This design cohort of 25 young people from a range of disciplines and a 50/50 gender balance has helped in every aspect of university life from campus layout, nightlife and accommodation to trialling some of the proposed courses.

One of the design cohort participants was keen to take part as she was attracted to NMITE’s proposal of a practical, workplace-based programme.

“Being a part of the design cohort was nothing but a great experience,” she says. “I learnt so much, broadened my engineering horizons, and met many interesting people. Every part of the course I trialled had real-world application and I gained skills such as communication and presentation skills, which aren’t directly connected to engineering but will really help in my career. I’m now even considering signing up for NMITE’s first student cohort.”

A design cohort of 25 enthusiastic young people has helped to develop the course programme

But the crucial question is, as set out at the very start of this project, will NMITE truly help to plug the engineering skills gap? Rodriguez-Falcon is adamant that it will and it will do it in two ways. The first is that, by undertaking around 30 problem-solving projects during the programme, NMITE will be able to deliver work-ready engineers to industry upon graduation. “We will effectively train engineers that can more rapidly and more readily join industry,” she says.

The second is that by showcasing what such a disruptive engineering model can achieve it will hopefully inspire other higher-education providers to follow suit. NMITE will then work collaboratively with them as they rethink their own provision. “We are talking to a university in the wider region who are looking at themselves and asking, ‘could we shake it up a bit?’ It’s difficult because their structures have been in place for many years but if we could be a catalyst, much like Olin College has been for the past 20 years, then the ripple effect could lead to a far wider contribution,” says Rodriguez-Falcon.

Recruitment drive

One key to addressing the skills gap is ensuring that more women are attracted to a career in engineering. “If 50% of the population are women, 50% of the engineers should be women, simple as that,” says Rodriguez-Falcon, who was Sheffield University’s inaugural director of women in engineering and led the creation of the first Women in Engineering student society in the UK.

To ensure gender equality across its programmes, NMITE has a few strategies. One is a targeted ‘recruitment drive’ for its first student cohort. “My somewhat crazy idea for our first student group is to effectively headhunt the type of learner that will benefit the most from this pedagogical model of problem-based, active learning, and certainly hands-on learners are not just men,” she says.

Being an outspoken adversary of the A-level requirements of maths and physics needed to pursue an engineering degree, which automatically rules out some students, especially girls, from pursuing engineering, NMITE will rather focus its application requirements on those who demonstrate the right aptitude and attitude to become engineers. “A student’s background might not be traditional but for us that is not a problem because what we want is for them to want to be an engineer, that they are passionate about it and have the grit and determination to do it, which will of course involve having to learn maths as part of the programme,” says Rodriguez-Falcon.

Rodriguez-Falcon's vision for NMITE has found plenty of supporters

“We would be open to offering scholarships. We also really mean what we say in having a gender-balanced student group. It’s not about having positive discrimination, it’s about making it happen. We will then hopefully start developing a culture and reputation, much like Olin have done, that will be attractive to future learners of both genders.”

But it’s not just about gender balance, it’s diversity in general and NMITE is practising what it preaches with staff members that reflect this diversity. And if role models are key to attracting diverse groups into engineering then Rodriguez-Falcon is an ideal role model, being an openly gay woman in engineering from Mexican heritage.

“If we plainly show our own diverse infrastructure and are open about things and if the actual curriculum is inclusive, it should certainly attract a diverse group of people,” she comments.

It’s difficult not to get swept up in NMITE’s vision and Rodriguez-Falcon’s culpable excitement for it. Will it work? Time will tell but as with any new venture it needs people to believe in it and support it, which there doesn’t seem to be any shortage of.

“Someone once said to me that the opportunity of a lifetime has to be taken during the lifetime of the opportunity. It’s a powerful quote. And the opportunity of rethinking engineering education and being part of that journey and that history making is something I’m extremely passionate about. I do hope that in a few years when we look back and we’ve delivered on what we said we would, we’ll say that it’s all been absolutely worth it,” says Rodriguez-Falcon.

Want the best engineering stories delivered straight to your inbox? The Professional Engineering newsletter gives you vital updates on the most cutting-edge engineering and exciting new job opportunities. To sign up, click here.

Content published by Professional Engineering does not necessarily represent the views of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers.