While technology is progressing at a rapid pace, enabling the development of bionic limbs that include sensors, motors and electronics, these are often out of reach of most users. “While research into new technologies and materials for use in prosthetics is vital and will benefit future innovations, in the meantime there are millions of people worldwide who are in need of solutions today,” says Nate Macabuag, founder of Koalaa.

London-based Koalaa was founded to create such solutions. Built on principles of simplicity and accessibility, its prosthetics for upper-limb amputees are soft and modular. Made from fabric, these slip-on prosthetics are comfortable, lightweight and affordable, and they come with various clip-on tool attachments depending on what the wearer requires, from holding a pen or cutlery to riding a bike and playing the drums.

“Koalaa is about accessibility. That’s at the heart of our small company – being accessible to every single person on the planet who might need to have some form of prosthetic support,” says Macabuag.

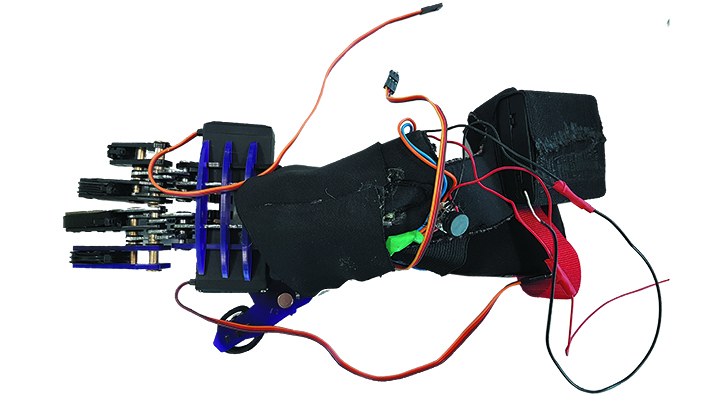

Noble intentions indeed, although he is quick to admit that their intentions weren’t quite as noble when they started out. At that early stage, drawn by the potential of “cool” technology, the aim was to create an Ironman-inspired bionic hand using sensors and electronics to power 3D-printed mechanisms.

The first prototype

Putting pen to paper

It was Macabuag’s third year at Imperial College London and as part of his masters degree in mechanical engineering his team proposed a robotic prosthetic as their project for that year. Having discovered that prosthetics have not fundamentally changed since the Second World War, especially in terms of the rigid materials used and the lengthy process required to make them, which contributes towards their exorbitant costs, they thought this was fertile ground to create something new and exciting. A robotic hand it was.

At that stage they were introduced to Alex Lewis, who had survived a serious reaction to a Strep A infection in 2013 but in so doing had undergone a quadruple amputation. While he did use his right-arm NHS-supplied prosthetic for most tasks, it was uncomfortable and rigid to wear all of the time and crucially could not perform simple yet intricate tasks such as holding a pen.

This became the brief and, ignoring Lewis’s pleas for a very simple and accessible tool, the intention was still to create a bionic hand with fingers that would enable him to pick up a pen and write. Easier said than done.

Macabuag spent nine months creating intricate robotic finger mechanisms. The day before the project report was due to be delivered, he still hadn’t managed to get the fingers to hold the pen. In desperation he ordered a 50p pen-holder clip off Amazon, and attached it to the palm of the bionic hand with the fingers enclosing the attached pen. Having access to some fabric and a sewing machine, they then very quickly hashed together a socket and bag for the hand.

“It was an abomination. We felt embarrassed to show this Frankenstein of a final prototype to Alex, but he loved it. We couldn’t believe it,” exclaims Macabuag.

“He specifically loved that the pen is completely secured by the pen clip and that the fabric socket felt comfortable and lightweight to wear. So the bits that cumulatively took us about 35 minutes were the bits he loved, whilst the nine months of serious engineering graft to create the finger mechanisms he dismissed. He went on to say that if he could buy this now he would.”

-alex-testing-our-first-prototype-(4).jpeg?sfvrsn=19966811_0)

Alex Lewis tests the first prototype

The prosthetics route

Buoyed by this feedback and having been awarded the Arup Prize for most outstanding third-year project, Macabuag felt inspired to develop the prosthetic further. “That feeling of being useful to Alex was just addictive and we wanted to help more people like him by creating super-simple, accessible and affordable prosthetics but needed resources and also we were still students,” he admits.

He managed to convince his supervisor to allow him to continue the prosthetic project into his final year, focusing on how to go about setting up a company, which he subsequently called Koalaa. Funding to further develop the design came from student competitions they managed to win. “For some of these the prize money was only £500 but, bearing in mind that the fabric needed to build prototypes cost just £15, it felt like infinite money. Towards the end of the year we won some bigger prizes that enabled us to file a patent, although we did have to live on beans on toast for a while,” smiles Macabuag.

Having graduated with a first-class degree in 2018, Macabuag spent two years growing his team and developing the prototype. When asked about the challenges faced during this process, he is quick to quip that it was all a challenge. However, he concedes that arguably the biggest challenge is working with textiles.

“Essentially we’re using the same processes as used to engineer trainers in that we’re taking textiles, forming it into a shape and then integrating semi-rigid components. But trying to reverse engineer a trainer and figure out how to use textiles to make functional products was a really fun problem,” he admits.

The forces a prosthetic applies or receives from the outside world was another key engineering challenge. Areas of the prosthetic that are taking load need to be rigid, whereas those that aren’t can be flexible. Determining where these areas are is the tricky part. “Then you have to add a transition between these two areas. From soft against the skin, you have to slowly transition to something that’s rigid in the right areas to do what you need the prosthetic to do,” says Macabuag.

Physical prototypes

To find the right solution involved much prototyping. Rather than using computer modelling tools, Koalaa created thousands of physical prototypes using low-cost materials such as cardboard and scraps of fabric in an evolutionary process. “We still have boxes and boxes of prototypes in our store room,” says Macabuag.

Koalaa regularly engaged with users to test its prototypes, not least of all because users come in different sizes. Users also helped inform the design of the injection-moulded, multi-functional tools that clip into the fabric sleeve to enable different tasks and activities.

Koalaa didn’t set out to completely replace prosthetics. The aim has always been to give users another option. For instance, Lewis, who was very much involved in testing prototypes, would mostly use his NHS prosthetic but, when he wanted respite or to carry out simple tasks such as holding a pen or picking up a wine glass securely, he would slip on his Koalaa sleeve.

“We want to give users the option to use something that can almost be considered a comfortable shoe or slipper. Choice is good. Our prosthetic is a tool to use when the need arises,” says Macabuag.

The final product is a soft fabric sleeve with a range of clip-on tools

Ready for launch

In 2020, Koalaa was in a position to launch its range of products. But launching a business involves far more than just developing products. As Macabuag admits, “We went into this thinking that ‘if we build it, they will come’. But, after our first prototypes weren’t selling, we realised we had to build a compelling end-to-end user experience around the product, and a holistic service that looked after each user. So we built a bespoke process to match users with their perfect prosthesis, and link users to a personal limb buddy who looks after them.”

Koalaa’s products are focused on three key users. First, kids particularly because they grow out of traditional prosthetics so quickly. Second, very recent amputees whose limbs are still too sore for a rigid prosthetic. Lastly, amputees living in middle- and low-income countries who often have no prosthetics available to them at all. In 2021, Koalaa successfully completed a pilot project in Sierra Leone.

Part of the firm’s mission to be accessible is to supply its prosthetics through a ‘virtual clinic’ where new wearers are measured, fitted and supplied with prostheses remotely. As Macabuag says, “Essentially we need two or three measurements. We then make the prosthetic to size, package it up in a big tube, and post it out within a matter of weeks.”

Children are one of three key user groups for Koalaa products, because they grow out of traditional prosthetics so quickly

Growing into the future

Securing investment from the British Design Fund, Koalaa plans to scale up. Having recently passed 500 users, it is constantly updating its product range and is focused on increasing manufacturing capacity at its west London facility. “We are now on the cusp of commercially selling accessible prosthetic arms that can be sent around the world for a fraction of the cost of anything else on the market,” he says.

But for Macabuag, who was recently named Forbes 30 under 30 for social impact, the drive is not to be commercially successful, the drive is to make the lives of users that bit easier with a simple and accessible solution. “I don’t subscribe to the idea that our products are life changing, what they do is enable users to carry out the little things in life they couldn’t before,” he says.

“We often get sent videos by proud parents showing their kids being able to do something that they couldn’t before like ride a bike for the first time. That feeling of being useful to someone is genuinely like a drug. Nothing beats it.”

Navigate a turbulent future by attending Aerospace & Defence (28 November – 2 December). Register for FREE today.

Content published by Professional Engineering does not necessarily represent the views of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers.