It was as though a Rubik’s Cube snapped into place in his mind and, all of a sudden, Sebhatu had figured out how to drill the perfect square hole.

Before the idea could flee, he drew a rough sketch on a napkin. He didn’t have all the details yet, but he finally knew exactly how he wanted the mechanism to behave. At last, Sebhatu understood how to convert the rotary motion of a regular drill into the linear motion required to drive four perfectly choreographed saws.

His first thought was: “Why didn’t I think of this before?”

“In some ways, I felt stupid,” Sebhatu recalls. “But, seconds later, you get this feeling of enlightenment and you tell yourself: ‘Yeah! This is going to work’.”

The idea to build what has become the Quadsaw began eight years ago, when Sebhatu watched an electrician battle to cut a neat square hole with a jab saw. When asked whether there was a faster way to do it, or a tool designed for the purpose, the electrician looked at Sebhatu as though he were from another planet. “Get me one, and I’ll pay you double for it,” he quipped. Sebhatu set out to do just that.

But to fully understand how the Quadsaw drill attachment came to be, one must rewind the story further and travel to a tiny village called Adi Golgol, a place mostly ignored by map makers, located 50km south of Eritrea’s capital Asmara, in the Horn of Africa.

Eyes to the sky

Sebhatu, 51, was born into a family of farmers in this village where, if a tool was required, it had to be made. He remembers watching his father work and, more importantly, he recalls spying on a local mechanic who came to fix their water pumps.

“He would come to our place and dismantle the whole engine,” explains Sebhatu. “He would put it on a clean cloth and then put it all back together. As a child, that got me very, very interested. I used to think: ‘How does he remember all these things?’ There are hundreds of bits and pieces… screws, washers, pistons… to me, they are all just shiny metal parts, but this guy puts them all together, tests the pump, puts petrol in and runs it. Just magic!”

With the precious memory swirling in his eyes, Sebhatu says he spent hours watching and asking questions, which were usually met with a chuckle. “That may be one of the reasons I got interested in engineering,” he ponders out loud.

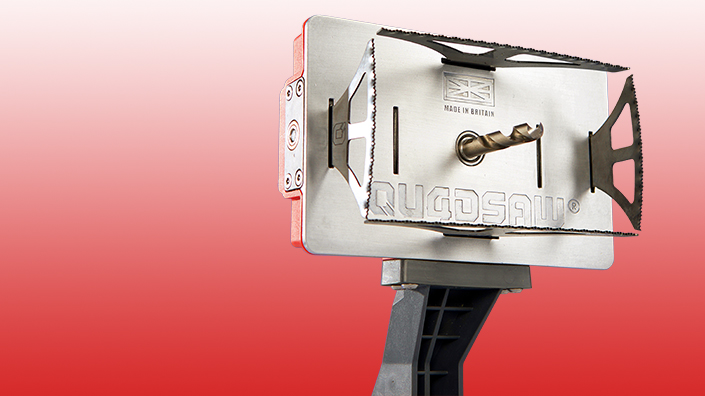

The Quadsaw (Composite credit: Quadsaw/ Professional Engineering)

Sebhatu was just starting school when war erupted in Eritrea. The Italian Catholic Mission that taught local kids closed and, until he was 11, Sebhatu herded sheep for his family in surrounding fields. He says these years, spent searching for food, protecting himself against dangers and caring for the animals, taught him to be creative. Then, one day, a strange object in the sky caught his attention.

“I was helping my father when I saw this thing flying. I looked at it, and looked at it. It was an aeroplane, but I was mesmerised for some strange reason… I started to think about how it flies. I couldn’t see wings flapping, like birds. So I asked my father but he was a farmer and didn’t know. He stopped what he was doing and looked at me. I still remember his smile.

“He said: ‘Son, if you want to know all those things, you’ve got to go to school’. He didn’t realise what he was saying to me… in the next three months, I told him I was moving to the city to live with my uncle and to go to school.”

Journey to London

In Asmara, Sebhatu returned to the classroom. Because of the long gap in his studies, he began by sharing desks with children half his age, but within three years he had caught up. Three times a year he would walk from the city to his village to visit his parents. He was one of eight children.

Later, Sebhatu’s elder brother, who was living in Ethiopia, invited him to join an engineering workshop he had opened. The invitation turned out to be Sebhatu’s engineering apprenticeship. He learned the trade and continued his studies. When he turned 18, everything changed. In a country with military conscription, Sebhatu found himself facing a cruel dilemma: either join the army or leave Ethiopia. “Joining the armed forces would mean going back to Eritrea to kill my own people,” he explains. So he left. He went first to Kenya, then to Sweden, through Norway and, eventually, in 1990, Sebhatu arrived in London, where he hoped to continue his studies.

With memories of that neat cloth and all those water pump pieces, Sebhatu worked his way towards a degree in mechanical engineering and then a master’s in product design. But jobs were difficult to come by, so he taught himself how to fit kitchens, inside one of which he eventually noticed an electrician hacking away at a wall, trying to install a square electrical box.

Breakthrough idea

With the napkin design he went on to draw at that London café, Sebhatu rendered a 3D version of his invention, ran simulations and got down to building a prototype. One of the biggest challenges was to make sure that the four blades, which sit at 90° angles to form a perfect 75mm square or a wider rectangle, don’t collide with each other as they slice through plasterboard. Sebhatu’s patent describes a spinning central cylinder with a groove around it in which a ball bearing sits, connecting the motion of the drill to the blades. The groove has carefully calibrated peaks and troughs, allowing the drill to drive the synchronised motion of the blades, and creating a smooth, clean cut.

Sebhatu refined the design until, in his eyes, it was perfect and his tool could be attached to any drill with a speed above 2,000rpm. He spent “every last penny” on the project, refusing to remain frustrated at having such a “breakthrough idea” locked inside him.

Two years on, Sebhatu met his future business partner Ean Brown, who was a lawyer looking for a new adventure. Sebhatu had the idea, Brown knew how to protect and market it. Their first meeting lasted three hours and before long they had joined forces. “Michael stumbled into my life,” says Brown. “This is a story of two people who are unlikely bedfellows, but who complement each other. You need innovation but you also need an understanding of how to commercialise it. Without the two going hand in glove, you’re unlikely to drive forward.”

Michael and Ean Brown proudly show off the Quadsaw

The new business partners were convinced that the Quadsaw had the potential to save the industry a fortune in wasted time. Estimating that 250,000 UK electricians cut an average of three holes each day, Sebhatu’s invention, they calculated, could save more than 16m hours of labour and over £300m a year.

“Michael had worked out how to drill a square hole,” says Brown. “Nobody had ever done it. People had tried. But nobody had nailed it. Michael nailed it.”

A decision was made to manufacture the tool in Britain and to focus on making sure each one was of such high quality that none was returned. The motto was “what gets sold, stays sold”. This meant the final price of the Quadsaw was significantly higher than originally planned, but Brown says the feedback has been fantastic.

“Enough have been sold for us to be satisfied as a business. But we need to sell more if we want to grow and be the business we want to be,” he says.

Excitement awaits

Sebhatu says he and Brown have been too busy to reflect deeply on the recent launch of Quadsaw.

“Maybe reflection will come when I see it in every building being built,” he adds. “Then I’ll know it’s making a difference.”

Sebhatu is a firm believer in apprenticeships and says young engineers have a lot to be excited about.

“Engineering is hard work. You have to be prepared to put in the hours,” Sebhatu says. “Because of technology, people are now used to pressing things on a screen and getting what they want… but engineering is a long process, it’s a build-up of experiences and setbacks. You need to be patient.

“It requires dreams and ambition. So just open your eyes – there are millions of problems in the world that need engineers to bring about solutions.”

For his part, Sebhatu says he’s finalising a new, top-secret invention, which he’s been thinking about for more than 25 years. He believes it’s another breakthrough idea.

As for Quadsaw, Sebhatu and Brown plan to start selling it in America later this year, adjusting the blades slightly to fit the standard sizes of electrical boxes there. They are also testing new blades to allow users to cut through materials such as wood, brick or tiles. At the moment, the Quadsaw is limited to use with plasterboard. There are conversations about lighter versions for ceiling lights, and bigger ones for air-conditioning units. There is no shortage of ideas at Quadsaw’s north London office.

Meanwhile, back in his home village in Eritrea, Sebhatu’s now 92-year-old father has been reading a local newspaper, which featured his son’s invention. “My sister told me that he was reading the paper for two weeks, again and again,” says Sebhatu. “He’s been showing it to people and telling them, ‘This is what my son did’.”

Perhaps he even remembers the plane that flew across the sky that day…

Content published by Professional Engineering does not necessarily represent the views of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers.