At the limb centre in Wrexham a 12-month-old boy is about to have a cast taken for his first prosthetic arm. The prosthetist instructs his assistant to hold the boy still. In his 40 years doing the job, he has never had a child that didn’t squirm and struggle.

But to his surprise the boy’s dad issues the simple command, “Sol, stump up.” And without fuss the boy extends his arm, severed just below the elbow, ready for the cast. The boy sits quietly and still throughout the whole procedure, leaving the prosthetist with a new experience in his long career.

The child isn’t a little angel. It’s just that his father, a self-taught engineer, has been making prosthetics for Sol – now three – since he was five weeks old. The father is Ben Ryan, a 41-year-old ex-psychology teacher turned self-taught engineer from Menai Bridge on Anglesey in North Wales.

Ryan’s journey to becoming a builder of bionic limbs started at his son’s birth. Complications with the delivery caused a white blood clot to form in Sol’s left arm. Doctors were forced to amputate just below the elbow.

Sol with one of the many arms his father has built (Credit: Iolo Penri)

Sitting by the baby’s bedside, researching on his phone, Ryan discovered that a prosthetic limb wouldn’t be available until at least age three, by which time there was a strong chance Sol might reject it. There and then Ryan, a keen mechanic but with no formal engineering training, decided to make his own working limb for Sol.

When Sol was finally discharged from hospital, Ryan was set to try his first makeshift prosthetic arm on his five-week-old son. “I got a piece of kitchen sponge,” says Ryan. “I rolled it up approximately to the length of his healthy arm and just used one of the dressings I’d seen the nurses at Alder Hey Children’s Hospital use, and I managed to get a little bandage arm to suspend.”

The results were spectacular. Within 10 seconds Sol had lifted the arm and started banging toys with it. From that day on, Sol was using both arms. It was the beginning of a three-year journey of ups and downs, breakthroughs, false starts and setbacks.

Funding crisis

When I first speak to Ryan he is facing one of those setbacks – perhaps the worst of his entire journey. Following an accelerated growth programme through Business Wales, Ryan’s company, Ambionics, had been set to receive matched funding of £50,000 from the Development Bank of Wales.

Instead, he has just been told, because his own funds weren’t applied to the company in the correct way, the £50,000 will no longer be available. He has been forced out of his business premises on a science park in Anglesey and is now back in the makeshift workspace off the back of his garage.

“I’ve got £3,000 left,” says Ryan, his voice sounding forlorn over a crackly phone line on a cold April morning. “It’s really depressing. There’s just no money in Wales. I need to get through this next six months somehow but, if I have to drop out and stack shelves, the project will die.”

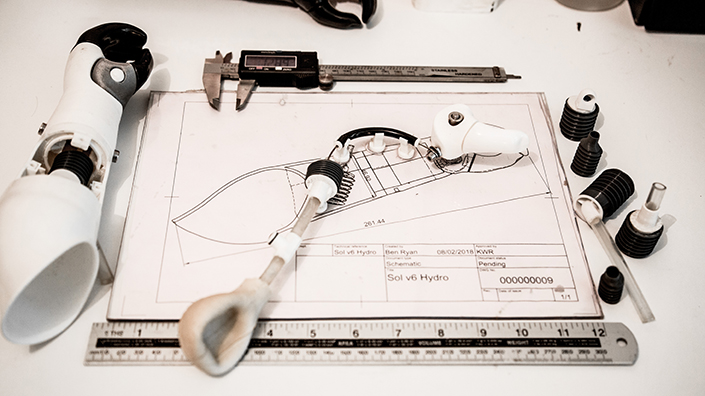

Ben Ryan taught himself how to use CAD software (Credit: Iolo Penri)

Ryan is no stranger to adversity. After the stress of the birth – both he and his partner, Kate Smith, were diagnosed as having post-traumatic stress disorder – he set about thinking of ways to improve his initial sponge arm to create a fully bionic limb.

He tinkered with various ideas involving batteries and microswitches but nothing really stuck. Then one night he had his eureka moment. “I was lying in bed and there was a spider in the corner of the room on the ceiling,” recounts Ryan. “I remembered that spiders use fluid pressure to activate their legs.”

Suddenly the solution hit him. “Instead of a microswitch, I could use a little bag of fluid in the socket and Sol could squeeze it, and somehow I could get that fluid pressure to close a hand.”

Feel the force

Ryan got straight to work using off-the-shelf components. He made a double-acting cylinder with two little fluid bags, one to open the hand and one to close it. He was able to show that it didn’t leak and that there was little enough resistance that a child of Sol’s age could activate it with enough force to be useful.

“It was a really stable system,” says Ryan. “It was one of those where you had to squeeze it with your fingers, and everybody who felt the piston rod come out the end was like, ‘Ooh, that’s quite a bit of a jolt’.”

The next stage was fitting it inside a prosthetic limb. Around this time Sol received his first NHS prosthetic arm. The cast fit perfectly around Sol’s stump, so Ryan took it to Bangor University where he obtained a 3D scan of the cast. A friend told him about free design software called Fusion 360, which could help him to create 3D-printable designs that would incorporate the two systems.

In a bid to help his son, Ben Ryan acquired a range of engineering skills (Credit: Iolo Penri)

“I think I watched YouTube tutorials for a month straight on how to use Fusion 360,” says Ryan. “And within three months I had a fully working hydraulic prototype printed.”

Ryan had already decided that the idea could be bigger than just one boy. He formed a company, Ambionics, crowdfunded some money and bought a 3D printer for £600 to start making his own version of the arm. The first attempt didn’t fit correctly but, after some tutoring from Autodesk, the creator of Fusion 360, he came up with a workflow to design a remarkably accurate socket that clung to Sol’s stump by suction alone. “I can pick Sol up by the arm and it actually supports his whole body weight,” confirms Ryan.

Ryan now had a prosthetic device that he thought could rival or better any the NHS could offer. It was time to test it. He’d already had hundreds of families contact him from around the world, asking if they could try his device. He drew up a shortlist and set up a beta trial, involving 20 families from countries including Albania, Ecuador, Australia and some African states.

Better than NHS devices

For one boy, just 20 miles away in Caernarfon, Ryan created a perfectly fitting limb in 28 days following four failed NHS attempts. And a 16-month-old girl had had several NHS arms, all of which had fallen off. Ryan’s device fitted perfectly, and the girl began reaching for his arm over the others. This was all the more remarkable because, owing to the necessities of cost cutting and simplicity, Ryan was using scans taken from an Xbox Kinect – a simple motion tracker used by video gamers.

But Ryan’s breakthroughs were punctuated by morale-crushing setbacks. He originally fell in a gap between investment sources so had to crowdfund money for prototyping, certification and patenting. He set up with a well-known crowdfunding platform asking for £150,000. There was a storm of media interest, which saw him doing TV and radio interviews around the world, including an appearance on Good Morning Britain on ITV.

Yet, despite the publicity, problems with the platform meant donations kept bouncing. Ryan lost thousands in possible donations and ended up with just £19,000.

Ryan has supplied prostheses to many children as part of a trial (Credit: Iolo Penri)

Bad luck seems to have dogged the process at every turn. An opportunity for a £1.3m business grant was squandered when Bangor University – the institution that had invited him to apply for the funding – forgot to put in an expression of interest supporting his claim.

On another occasion, one of the fathers whose child he was helping offered to assist with scanning for the beta trial. Ryan sent him a laptop and taught him everything he needed to know but heard nothing back from him.

“It turns out he was setting up his own rival project,” says Ryan. To add insult to injury, the man received some of the funding Ryan had been unable to obtain because he was based in England rather than Wales.

Undaunted, Ryan keeps pushing on. He intends to relocate to England where he has been offered business premises at the 3M Buckley Innovation Centre in Huddersfield, West Yorkshire. Despite the setbacks, he has a clear vision of where his firm Ambionics can go, including using new technology such as artificial intelligence (AI) to take over the time-consuming process of designing the sockets.

“What I’m looking at in three years’ time is fully functional bionic arms partly generated by AI and constructed purely using a machine with no human intervention at all,” he says.

Renewed impetus

It has been a long and tortuous journey which, for a while, faced the threat of a premature end. It seems, by chance, I caught Ryan at a crucial crossroads. For a few days before our first chat he had been seriously thinking about giving up.

When I speak to him again, a month later, several sources of funding now look on the cards, including renewed backing from the Development Bank of Wales, a wealthy London venture capitalist, and a crowdfunding campaign backed by Autodesk and RS Components.

He is also a finalist for Nesta’s prestigious Inventor Prize. He sounds more motivated than ever to continue.

“What keeps you going?” I ask him, referring to the dark times and setbacks. His answer may not be pretty but it is honest. He identifies it as a mix of being an “arrogant bastard” who wants to prove he is right, and anger at Sol’s plight.

“Everyone wants to hear that it was out of love,” he says. “And of course it was. But it was anger that drove me on. I couldn’t let this happen to my son. I wanted him to be a bionic boy.” He pauses, as if realising just how far he and Sol have come. “And now, here we are.”

Content published by Professional Engineering does not necessarily represent the views of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers.