In 2018, the aerospace engineer was addressing a conference panel of entrepreneurs working on electric vertical take-off and landing vehicles (eVTOLs).

These futuristic vehicles are swooping out of the military and towards the commercial market as flying taxis and business aircraft. Specialist start-ups and veterans such as Rolls-Royce and Bell promise to revolutionise inter- and inner-city travel with quick, green and flexible flights. Backers predict autonomous flights soon, and manned flights sooner – but serious barriers remain.

Challenge one: Range

.jpg?sfvrsn=8a98812_0)

Vertical Aerospace swooped onto the scene last year, the first British company to test a flying taxi (Credit: Vertical Aerospace)

Wright’s question to the eVTOL entrepreneurs was simple: “What’s your biggest headache?”

“Oh that’s easy,” they told the University of the West of England (UWE) associate professor. “Batteries, batteries and batteries! If we could only multiply the amount of energy we could contain in a battery, that would change everything.”

Energy density affects everything in eVTOLs, but perhaps its most fundamental relationship is with range. Batteries power the motors, but are also very heavy – you cannot simply add more and fly further.

The field’s early players have fought scepticism to position their concepts as viable near-future transport options, but will enough people choose eVTOLs over cars or trains if they cannot fly further than a few dozen kilometres?

Bristol’s Vertical Aerospace has first-hand experience with battery limitations. In September 2018, it was the first British company to successfully test a flying taxi. Now, it is using lessons from that trial to take the next step – but progress is far from easy.

“The technology is only just good enough… everything is at a limit,” says head of power and supply Lawrence Blakeley. He estimates a maximum 20-30-minute flight time using the current batteries, which are typically found in power tools or cars.

“I don’t see any major improvements happening in the next two, maybe even three years. But there is a significant amount of investment happening around solid-state batteries, and this is where I see growth and improvement in range capability.”

Solid-state batteries use solid electrolytes, instead of the liquid electrolytes of typical lithium-ion batteries. They could offer two and a half times better energy density, faster charging and longer life – all incredibly desirable for manufacturers, a potential paracetamol for the range headache. Manufacturers are also investigating hydrogen fuel cells.

In the meantime, eVTOL pioneers have to face an uncomfortable truth – batteries are just not good enough. Instead, several concepts are more like hVTOLs – hybrid vehicles, using batteries alongside conventional engines.

A partnership with Uber, 84 years of experience and production of the Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey – the first production tiltrotor aircraft, combining helicopter-style vertical flight with aeroplanes’ speed and range – makes a Bell a likely contender for leadership in the commercial VTOL space, and its approach with its Nexus air taxi could show the likely path ahead.

Partnering with Electric Power Systems and Safran on energy and propulsion, Bell’s aircraft will use batteries as either a main or complementary power source, and also a gas turbine to drive an electric generator. A distribution core will monitor the ‘hybridisation’ level, sharing energy between electric motors for each of the aircraft’s six propellers.

Although hybrid propulsion could offer the range required, any fuel burnt would have a major impact on sustainability credentials at a time when emissions are under greater scrutiny than ever before. Other design aspects could help maximise range without reliance on fossil fuels.

Engineers have to make difficult decisions on ducted fans, for example – included on Bell and Vertical Aerospace’s designs, these can increase aircraft efficiency but add extra weight and drag.

Unlike many of the concepts revealed so far, wings could be common to help minimise energy use on future VTOLs.

Challenge two: Safety

Transcend Air and BRS Aerospace hope the Vy 400 will be the 'safest VTOL aircraft in history' (Credit: Transcend Air)

For every 100 million miles driven by passenger cars in the US between 2005 and 2012, NASA statistics show one person died. On motorcycles, it was more than 27. General aviation – private flights, often using small aircraft – resulted in over 15 deaths, but airline flights just 0.2. It is the equivalent of one catastrophic failure every billion hours.

The risks of VTOL crashes are clear – flammable batteries, spinning propellers and built-up areas are not a good mix – so to keep people safe, some manufacturers claim they are aiming for airliner levels of safety.

“If you want this type of aircraft to be a big part of the future of transport and infrastructure, we need them to be far safer than cars, far safer than existing light aircraft, especially rotorcraft,” says James Peck, head of structures at Vertical Aerospace.

One catastrophic failure every billion hours is unrealistically optimistic, says the UWE’s Wright, but manufacturers are chasing that figure by introducing redundancy measures. Designs increasingly include eight, 10 or more propellers and coaxial offsets, with rotors positioned on arms away from the body of the aircraft. The approach increases thrust for a given area.

“The other big advantage,” says Wright, “is if you lose one rotor you don’t fall out of the sky – which you can imagine is very pleasing if you’re flying in it.”

Companies are also duplicating motors, switching devices, battery packs and more, as they aim to ensure that passengers can always safely reach the ground.

“That comes at a price,” says associate professor Wright. “It’ll often add weight… you’re paying a very heavy price in terms of performance, cost, complexity – and, ironically, the number of times the thing breaks down, albeit breaks down safely, will actually go up.”

Other features will help keep commercial VTOLs safe. Vertical Aerospace and others promise fly-by-wire controls, unusual for small aircraft.

Solid state batteries could be less flammable. Operators and pilots might plan safe landing spots at regular points along routes, or could fly above rivers to protect people on busy roads.

At the more exciting end of the safety spectrum, aircraft-attached ballistic parachutes could be installed to deploy in the event of power loss or other faults. BRS Aerospace, which claims to have saved 401 lives with its rocket-deployed chutes on Cirrus and Cessna small planes, has reportedly partnered with Transcend Air to work on the Vy 400 – a six-seat aircraft they aim to make “the safest VTOL aircraft in history”.

However manufacturers do it, they need to do it quickly.

“We have to get it right early on so that the public’s perception and the perception of the authorities is that these are very safe aircraft,” says Peck. “That is the biggest challenge, making sure that all the architecture you come up with can demonstrate that and give the general public and the authorities confidence – despite it looking somewhat novel and unusual.”

Challenge three: Regulation

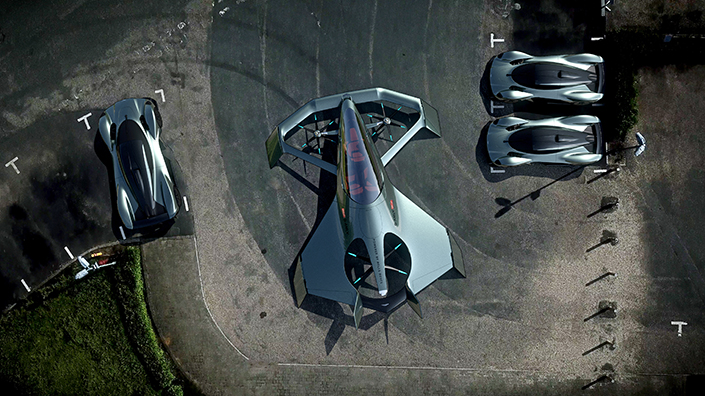

The Volante Vision concept is aimed at urban flights (Credit: Eleanor Bentall/ Aston Martin)

Electric scooters are banned on the roads and pavements of London – what chance do flying taxis have in the sky? Although many VTOL companies hope to revolutionise urban transport, Vertical Aerospace believes inter-city routes will be key to the technology’s initial success.

“Prove that it’s incredibly safe, prove that it is incredibly convenient and that there is a good carbon saving,” says a spokeswoman for the company. “Once that is done, and you know that you can do this in a safe way, you would then move to the shorter, around-city-type routes.”

Blakeley says regulators will expect Vertical Aerospace to meet airline levels of safety, due to the complexity of their vehicle and the inclusion of enabling technology. The company is confident it will meet requirements, thanks to ongoing discussions with the European Aviation Safety Agency, which is responsible for both certification and regulation (at time of going to press). Companies that have previously released ambitious concepts might struggle to back-fit regulation-compliant technology without compromising their visions.

Air-traffic management will itself have to change to cope with any VTOL influx, says Vertical Aerospace chief certification engineer Paul Harper.

“When you get to a very traffic-dense environment, the usual methods are probably not going to hold out.”

Industry will participate with the regulator on a unified air-traffic management system, he says, a “more managed and more integrated atmosphere and environment”, where a “data net” includes not only aircraft location, but also capabilities. The system can then manage vehicles based on their characteristics, and those of the surrounding craft.

Projects such as the National Beyond visual line of sight Experimentation Corridor from Cranfield University and Blue Bear Systems Research are laying the foundations for integrated drone flights in urban airspace. “It then becomes a stepping stone into looking at urban air mobility, where we look at swapping freight out with passengers,” says Cranfield director of aerospace and former managing director at Airbus UK Iain Gray.

At times, the challenges seem insurmountable and the VTOL vision unrealistic. But Gray, described as “probably the most credible man we have in the industry in the country” by the Vertical Aerospace chief commercial officer, says he has “absolutely no doubt in my mind that we are at a tipping point in technology terms, where this can happen”.

Gray, who was also the former chief executive of Innovate UK, is working with Aston Martin and Rolls-Royce on the luxury Volante Vision flying taxi concept. Speaking about industry progress, however, he says: “My belief is it will take significantly longer than perhaps people are thinking.”

He adds: “I wouldn’t underestimate those challenges, but nor would I approach it by saying: ‘This is just a natural extrapolation of 100 years of flight,’ because there are people out there with new ideas and ways of looking at things…

“I wish I was joining the sector now.”

Content published by Professional Engineering does not necessarily represent the views of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers.