The UK is facing an energy crisis, and the recent discovery of shale gas in north-west England is heralded by some as one way of becoming self-sufficient and obtaining sustainable power supplies. But others disagree, saying that a shale gas industry could have environmental impacts and is not a long-term solution to the problem.

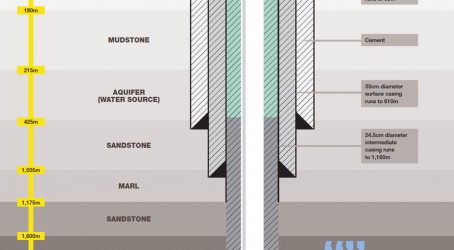

Shale gas is extracted by a process called hydraulic fracturing. This involves drilling into shale rock formations that lie thousands of feet beneath the earth’s surface. A series of steel tubings are cemented into the ground, to contain the well. The end of the steel tubing is then perforated by a small electric charge to give access to the shale formation.

A combination of water, sand, and small quantities of a friction reducer and biocide, known as fracking fluid, is pumped down the well. The pressure forces the fluid through the perforations and into the shale bed where the rock is prised open to create tiny fractures that migrate in all directions. These fractures are held open by the sand particles in the mixture, so when the fluid is pumped out the gas trapped within the rock escapes to the surface. A typical frack lasts around three hours.

Fracturing has been used in the oil and gas industry since the 1940s. But the use of fracking in shale formations was pioneered by the Mitchell Energy and Development Corporation in the Barnett shale, Texas, during the 1990s.

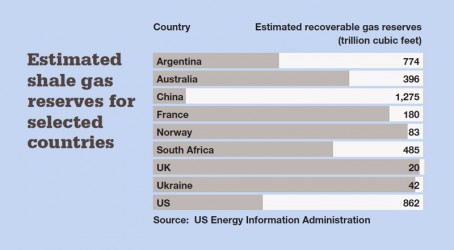

Over the past 20 years, the US shale gas industry has boomed. In 2011, the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) reported that US shale reserves harboured 862 trillion ft3 of recoverable natural gas, double the estimate published the previous year and comprising 34% of the country’s total natural gas base. The EIA believes estimates are likely to increase in the future, with shale gas comprising 46% of the country’s natural gas by 2035.

Although the US boom has transformed the energy landscape, it has brought with it some unwanted environmental effects. An Oscar-nominated documentary, Gaslands, famously shows residents setting fire to the water coming out of their taps after the shale gas companies have come to town. In other scenes, homeowners draw brown and murky water from their taps.

Late last year, the US Environmental Protection Agency published the first formal findings of groundwater contamination caused by fracking. Draft findings from an investigation in Wyoming reveal that local groundwater had probably been contaminated with synthetic chemicals associated with fracking, and had high levels of benzene and methane gases. The exact mechanism behind the contamination remains unclear.

The controversial practice has now arrived on UK shores. Last year, independent energy company Cuadrilla began exploratory work to better understand the prospects for natural gas in the Bowland Shale around Lancaster.

Since the start of the exploratory programme, fracking has barely been out of the headlines. Environmentalists have called for a moratorium, MPs have held an inquiry into its potential effects, and two earthquakes in the area concerned have halted proceedings.

Further afield, the French and Bulgarian governments have banned the technique, and fracking-associated earthquakes have been reported in the US state of Ohio.

Cuadrilla’s exploratory project in Lancaster remains on hold until the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) looks into the recent seismic activity. A report commissioned by the company and submitted to DECC says that the quakes, measuring 2.3 and 1.4 respectively on the Richter-scale and two months apart, were a result of a well at Preese Hall encountering an existing critically stressed fault.

Paul Matich, well services manager at Cuadrilla, says: “The fault was transmissible, so it would accept large quantities of fluid, and the fault was brittle enough to fail seismically.”

The report says that the opening of the hydraulic fractures is unlikely to have triggered the quakes because they occurred 10 hours after the injection of fracking fluid. Instead, the pressure from the fluid built up on an area of the fault zone over time. The report adds that similar events are very unlikely to happen again because the chances of any one of these factors occurring alone is small, with the chances being even smaller in combination.

Matich adds: “This was a very unusual situation. There is fracking going on all over the world every week, and the amount of seismic events that have happened is a very small number.”

If Cuadrilla gets the go-ahead to continue fracking, there are measures it can take to curb the risk of further earthquakes. These include early warnings and detection systems for seismic events. Previously, no seismic monitoring had been done at the site.

Changing the regime of fracking is another option. “We may look at doing two or three smaller fracks in the same zone, rather than just doing one large frack,” says Matich.

The Preese Hall well, near the village of Singleton, runs down to 9,600ft. It is one of three wells that Cuadrilla has drilled, and is as yet the only one to be fracked. Around three miles away is the second well at Grange Hill, and a third well lies 20 miles away, south of the Ribble Estuary, and runs down to 10,400ft.

In total, four or five wells will be needed to complete the exploratory work. The work will evaluate the number and thickness of shale formations, as well as the quality and quantity of gas that can be obtained from them.

Initial analysis suggests the area contains a “substantial” reservoir within the Bowland shale, according to Matich. In-house geologists believe that there is 200 trillion ft3 of gas trapped within the shale formation, which runs from Preston to the Irish Sea. The estimates will be more precise once the exploratory phase is over, which could take up to a further 18 months.

But Matich says that not all of the gas can be recovered from the region. “Producing it and getting it to the surface economically is not an exact science. We may only get 10-15%,” he says. “But even at this proportion, the volume that we are looking at is quite substantial.”

Progressing to production would see another 200-300 wells drilled over the course of three to five years using a pad-drilling system. This involves setting up the rig on a small pad, which operators can then use to skid the rig a few metres in each direction. This way, they can drill 10-12 wells without the disruption of dismantling and re-erecting the rig for each well.

It is not yet clear for how long each well would continue to produce gas. Matich says that no formation is the same, but that some fields in the US are still producing gas after 18-20 years.

Commenting on the potential for water pollution at the site, Martin Diaper, a climate change consultant at the Environment Agency, says that the risk of groundwater contamination is low.

During the process, it is not possible to get all of the fracturing fluid back to the surface. “Some is locked into an underground shale formation. But the possibility of that leaching or moving through several thousand feet of rock is exceedingly small.”

This is because the chemicals will end up trapped in the shale rock in the way that the gas was. “The gas hasn’t been able to migrate because the rock isn’t permeable,” he adds.

Rob Ward, head of groundwater sciences at the British Geological Survey (BGS), agrees that the risk of groundwater contamination is low. The fracking zones are so far from the overlying aquifers that pollutants would have to travel “very significant” distances to contaminate. Ward adds that the UK has planning and environmental protection controls that are among the tightest in the world.

Diaper adds: “We have seen all the bad stories that have come out of the US, but there are loads of wells where there have been absolutely no problems.” He says that the Environment Agency will work to ensure that there are no problems on the site.

Ward says that in most US cases, the level of methane present in the affected groundwater was not known before fracking began. This makes it difficult to attribute the methane in the water to shale gas activities. Methane can come from several sources, including landfill and the microbiological degradation of organic materials, he says.

To prevent any similar uncertainty in the UK, the BGS has begun a groundwater-sampling project that will assess the baseline levels of methane, carbon dioxide and other light hydrocarbons in areas that might be exploited for shale gas. In areas that are flagged as having levels higher than expected, further sampling and isotopic testing will allow geologists to take a “fingerprint” of the gas to help determine its potential origin.

Although the BGS is hot on the trail of potential contamination, no sampling of the aquifer at Cuadrilla’s Preese Hall site has been done. Diaper says that this is a saline aquifer, which is not used for drinking water, and lies much deeper than a potable aquifer would.

He adds that Cuadrilla routinely monitors the surface water at the site for contamination, and so far no pollution incidents have been reported.

Some scientists have concerns over the adequacy of the current regulatory framework for fracking in the UK. A report on the environmental impacts of shale gas published by the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, and funded by the Co-operative, says that polyacrylamide, the friction reducer chemical used in Cuadrilla’s fracking fluid, may not be permitted for this use under the European Union chemicals law Reach.

Acrylamide, a component of polyacrylamide, is on a European Chemical Agency list of substances that are subject to strict regulation in the EU. Diaper says that the Environment Agency, which is responsible for enforcing Reach in the UK, has assessed the chemical and believes it is safe for use in fracking. He adds that as he understands it, the quantities of polyacrylamide currently used by Cuadrilla are too small for the regulation to be applicable. But whether the chemical can legally be used in fracking is the subject of an ongoing investigation in Brussels.

Kevin Anderson, director of the Tyndall Centre at the University of Manchester and one of the report’s authors, says that pursuing shale gas could throw the UK off track with climate change goals. “We are developing another high-carbon fossil fuel at a time when the globe repeatedly claims it wants to meet much lower-carbon futures,” he says.

An absolute exchange from a coal-fired power station to a shale gas one would be beneficial. But problems come when a shale gas power station is built, as then an existing coal-fired station would have to be shut down or a new one not built. “Our view is that because there is a very high energy demand around the world, if we use shale gas someone else will consume the coal that we would have, so there is no substitution impact,” says Anderson.

The UK government’s own committee on climate change is aiming for a 60% reduction in carbon emissions by 2030 based on 1990 levels. Even using shale gas as a transitionary fuel does not stack up, says Anderson.

Given that shale gas power stations will not be built significantly until 2020, they will have to close down again by 2030, he says. Investment in shale gas could divert funds away from more carbon-friendly power sources.

Anderson also warns that the industry needs to slow down. “The clamour to get the gas out of the ground seems to be the main driving force, and the regulations look like they will be following,” he says. “The lesson from the US is to be prudent, precautionary, and make sure the regulatory framework is in place beforehand.”

He adds that several issues need to be fully thought through before full-scale extraction begins in the UK.

These include a clear regulatory framework for emissions monitoring and for ground- and surface-water contamination, as well as a strategic plan for getting water to wells for use in the fracturing process.

US focuses on monitoring and efficiency

While the UK debates how best to get the industry off the ground, operators in the US are developing advanced techniques to aid gas recovery and mitigate potential environmental effects. David Cole, well-drilling lead for production technology in the upstream Americas region at Shell, says that a lot of work is going on to develop monitoring systems. These include microseismic devices that can track the location where rock is breaking. Fibre-optic technologies are also helping operators to monitor temperatures. In addition, systems are being developed to help improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the fracturing process. One example is using swellable packers and ball drops to direct the fractures through the rock.