In the land of science fiction, ultrasonic waves are very useful. Dr Who’s trusty sonic screwdriver gets him out of all sorts of trouble – he points it at doors and ultrasound waves unpick the lock. But what use could this technology be in the real world?

Quite a lot, say scientists from several universities around the country who are investigating how ultrasound can be used to manipulate objects. They believe that ultrasonic forces hold huge potential in areas as diverse as medical and materials sciences.

The sound waves can be used to suspend cells in a liquid so that they can grow and divide to create replacement body tissues, for example, or for micro-scale manufacture of new composite materials, they say.

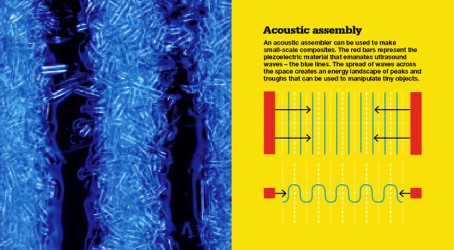

One of these scientists is Bruce Drinkwater, professor of ultrasonics in the department of mechanical engineering at the University of Bristol. He runs a £4 million project with the universities of Dundee, Glasgow and Southampton that is investigating the potential of this technology, known as acoustic assembly. He and his colleagues have devised a series of simple devices that use ultrasound to suspend cells and other small particles in space. The process relies on special materials, dubbed piezoelectric, that convert electric energy to mechanical energy. This conversion takes place thanks to the granular structure of the materials. Each grain is similar, but they are orientated differently. So when electricity is applied to the material it causes the atoms within each crystal to move a tiny amount, which creates strain. It is this strain that creates ultrasonic waves to ripple out of the material.

The waves have high frequencies – in the megahertz range with millions of cycles per second – and travel across a given distance in a solid, liquid or gaseous medium. The waves create a pattern of energy with peaks and troughs, and if tiny objects are introduced to the medium they get pushed around. Objects will settle in the troughs of the waves, where energy levels are lowest, rather as a marble will roll to the bottom of a hill. The objects that can be manipulated in the ultrasonic waves are tiny – cells, small beads or micron-scale fibres – and the devices set up force fields that are just several centimetres wide.

The frequency of the waves dictates the spacing between each wave front, and this can be altered by tweaking the thickness of the piezoelectric material.

A simple acoustic assembly device that is used to arrange cells may have four elements of piezoelectric material arranged in a square. As the ultrasound waves flow out of each element they interfere with each other and produce a grid-like pattern. The cells are then held in a series of rows. Drinkwater says that this could allow medical scientists to run many experiments in parallel. “If you were doing drug toxicity testing it could be very useful,” he says.

One cell can be introduced to another of a different type to study interactions in this kind of set-up too. Devices that manipulate cells could have ultrasonic waves emanating from the bottom of the device too so that the cells do not touch any surface.

The latest devices have 16 elements of piezoelectric material arranged in a circle that can be fired in different patterns to hold an object in a specific place. Sandy Cochran, professor of biophysical science and engineering at the University of Dundee, is working with colleagues on the manufacture of these prototype devices.

The team starts with piezoelectric ceramic or crystal and uses lapping and polishing machines to thin the material, and a dicing machine built for the semiconductor industry to cut it. The resulting pieces are around 0.25mm in length, and any number of these can be used as the source of ultrasound waves in a device.

“They are really tiny parts and we have to look at them under a microscope,” he says. Working at this scale means the already specialised machinery is used in new ways. “It’s not possible to just buy a machine, plug it in and start using it at the scales that we work with. We need to know more about the machines than a normal end user would,” says Cochran.

The material is very hard and the structure throws up challenges for the researchers.

“It complicates our lives because we have to understand how it works. A huge amount of our work is in understanding what the material does if you put some electricity into it,” he says.

Newer piezoelectric materials are crystalline and can produce higher-amplitude ultrasound waves for a given electrical signal than ceramic versions but at 50 US cents per cubic millimetre they are 100 times more expensive. As only small amounts of the material are needed for the acoustic assembly devices, Cochran expects that the crystalline version will be used in products.

Cochran’s work also involves integrating the acoustic platform with electronics to create a coherent device. This will make it possible for the technology to be readily used on desktops in laboratories, he says. By contrast similar techniques, such as optical tweezing – which uses light waves to move slightly larger particles around – require a lot of “bits”. These include a laser, beam path and a way of generating holograms, for example. “Optical tweezers in the life sciences laboratory can be a bit of a liability,” adds Cochran.

Completed systems are tested in Cochran’s laboratory to see whether fluorescent beads, microfluidics or cells can be manipulated with acoustics under electronic control. As part of this work Cochran is looking at the phenomenon of chemotaxis – a process of chemical signalling that controls the movement of cells in a developing embryo. Research has suggested that cells can sense and respond to chemical gradients, and in development cells are attracted to the source of the chemicals – nutrients.

“We have been looking at whether we can stop the cells from moving towards the source of nutrients and measure how the forces that the cells exert change,” Cochran explains. But so far this has proved unsuccessful because the acoustic devices cannot produce sufficient forces.

Using acoustic forces to study chemotaxis and other biological processes is under way in the engineering sciences unit at the University of Southampton. Martyn Hill, professor of electromechanical systems and head of the unit, has been working on acoustic assembly technologies for more than 15 years.

At first his research focused on filtering, concentrating and processing bacteria. These techniques make it possible to detect pathogens in water supplies, or to remove particles and cells from small samples of fluid, for example.

But his latest work with Drinkwater and Cochran involves using sound waves to create cellular geometries and structures that could one day help to grow human tissues and organs outside the body.

At the moment, Hill and his colleagues are working with cartilage – a tough, flexible tissue that covers the surface of joints so that bones can slide over one another. Cartilage is prone to damage from accidental falls and wear and tear in old age. The tissue does not have its own blood supply so cannot heal as quickly after damage as other types of cells.

Scientists have been working for more than two decades to grow cartilage outside the body to replace damaged tissue, but so far little technology has made it out of the laboratory to reach the patients.

Researchers can grow cell structures on a growth medium in Petri dishes but these tend to sit on the bottom of the culture plates, which can be problematic when removing the cells and does not mirror how the tissue develops in nature. When grown in a test tube, cartilage cells form balls and those in the centre die because they have no access to nutrients.

By using a specially designed ultrasonic assembler, Hill can create “pancaked shaped” cell formations. He explains: “None of the cells are very far from the nutrients and growth medium. So you should be able to grow bigger structures without getting this cell death in the centre.” The force field levitates the cells so they tend not to interact with any surfaces. There are other advantages too, says Hill. Exposure to ultrasound waves mechanically excites the cells, which triggers them to form a good extracellular matrix – the part of the cell that gives cartilage tissue strength.

Although the research is still at an early stage it could be as little as five to 10 years before the technology is ready for clinical use, depending on the outcome of these prototype studies. In the years ahead, Hill sees ultrasonic assembly being used to levitate bone stem cells and nutrients in specific places around a biodegradable scaffold to create bone tissue with the trabecular structure seen in nature.

Hill says: “Our biggest challenges are making a technology that has been developed in an engineering department suitable for use by biologists.” For many years, researchers had used small beads and simple cells in the devices. But, more recently, researchers have become interested in culturing cells for prolonged periods. This means that the devices have to be made sterile, and scientists must be able to control the temperature and gas balance of the medium, which is tricky. There can also be issues with getting cells out of the devices without damaging them.

Back in Bristol, Drinkwater is looking at how ultrasonic assembly could be used to develop composite materials. “Over the past few months we have made our first pieces of the material and we are in the process of proving that it has clear advantages,” he explains.

The material is created by an acoustic assembler with two opposing piezoelectric nodes. The ultrasonic waves emitted from each node push tiny 50-micron glass fibres to collect in the low-energy parts of the field. Hundreds of these fibres collect to create a series of stripes in an epoxy matrix. Within each stripe the tiny fibres are not aligned with each other but point in many different directions, which gives the material mechanical properties in a variety of planes. Conventional composites have stripes of long fibres that only offer strength in the in-plane direction.

Drinkwater says the devices could be used to create materials that can be moulded into complex shapes and curved around corners in a way that conventional composites cannot be. The current composite manufacturing process involves layering flat sheets of material on top of each other by machine. For curved or corner designs the process is often done by hand and involves cutting and sticking down layers, which can give overlaps and discontinuities. “Ultimately we are interested in carbon fibres,” he adds.

There are limitations with the approach. Any fibres introduced into the acoustic field cannot be longer than the wavelength itself. Drinkwater says: “It is working well with smaller fibres where both dimensions are smaller than the wavelength. We have tried it with longer fibres and it doesn’t work so well because they get stuck, but there are ways around that. We can use other processes like flow or a magnetic field to get them going.”

Scaling-up the technology will pose further challenges because the amplitude of the ultrasound waves diminishes with distance from the nodes but it is not yet clear where the limit stands. Drinkwater says: “Things of A4 scale could be possible. Beyond that there is quite a lot of work to be done.”

The potential of acoustic assembly technology has already excited some industries. Several companies that make equipment for life science laboratories have taken an interest. Drinkwater is also working with a major player in the aerospace industry.

Drinkwater concludes: “It is early days. Whether you get the killer applications next week or in several years, it is really hard to say.”

Creating models of tissues

Dr Umut Gurkan, assistant professor at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio, says that one of the challenges in tissue engineering is bringing together the cells in controlled geometries that mimic real tissues in a rapid manner. “We need technologies that can do this, and acoustic assembly is one of them,” he says.

Gurkan says that acoustic assembly has a lot of potential to create in vitro 2D and 3D tissue models, which can be used for drug testing and other research. He adds: “There are many other technologies out there but not all of them can achieve this in a rapid, repeatable and non-invasive manner. The low-intensity sound waves are not harmful for the cells.”

Acoustic assembly is slower than other methods such as magnetic and fluidic, he explains. Magnetic fields can be more accurate but are more expensive and require more complex instrumentation. Gurkan adds: “More research is needed before acoustic assembly can be used to create complex structures but simple structures with two or three cell types are close to being useful in real-world applications.”