Articles

Since Japan’s Shinkansen service opened in 1964, 16 countries now have 28,000km of high-speed lines operating at more than 250km/h. High-speed rail also drives the modal shift needed for decarbonisation both by attracting passengers from planes and cars and by providing extra capacity on existing lines.

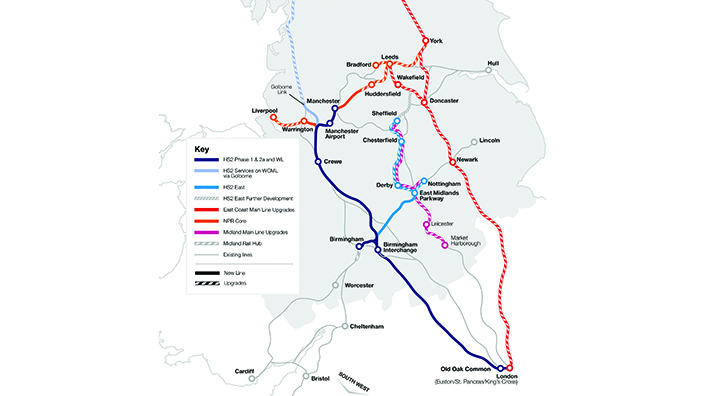

Britain’s first domestic high-speed railway, HS2, was proposed in 2009. This 530km Y-network between London, Manchester and Leeds was also to be connected to other lines to take HS2 trains to Scotland and Newcastle. HS2 was also to provide estimated capacity relief on the West Coast, Midland and East Coast main lines of 67%, 33% and 50% respectively

Until recently the project enjoyed cross-party support, including commitments from the prime minister to deliver HS2 in full. However, it was appallingly sold. Until recently, there was nothing to counter the view that it is a vanity project costing billons to save a few minutes between London and Birmingham.

Cuts and cancellations

This falsehood was a factor underlying the recently published Integrated Rail Plan (IRP), which the government hailed as transforming rail links in the North. Yet in reality it cut back Transport for the North’s proposals for Northern Powerhouse Rail and cancelled the most transformational part of HS2’s proposed Y-network by curtailing the eastern leg to Leeds. This is replaced by an upgraded East Coast Main Line (ECML) service to Leeds.

IRP claims that upgrades, including 225km/h running, would reduce the London-to-Leeds journey by 20 minutes. Yet only five minutes would be saved if the heroic assumption is made that all current 200km/h sections could be upgraded to 225km/h running. Furthermore, running trains at this higher speed on a mixed-traffic railway will reduce capacity.

IRP also claims that its proposal will cause less disruption than HS2 by overstating the disruption from building its bridges over the motorway network. Yet it barely mentions the huge disruption from upgrading the ECML to HS2’s same capability. A recent report showed that this would require almost 10 years of continuous weekend possessions.

Curtailing the eastern leg also fails to make the best use of HS2’s core route from London. With more HS2 services running on the conventional network, the planned 18 trains an hour from London Euston may not now be feasible.

The IRP plan terminates HS2’s eastern leg at East Midlands Parkway so its trains can run directly to either Derby or Nottingham. While this benefits both cities, the result is that HS2 will no longer relieve capacity on the ECML, and Leeds becomes IRP’s biggest loser.

Transport for the North, the statutory body set up to plan the region’s long-term infrastructure investment, also saw its proposed Northern Powerhouse Rail (NPR) cut back despite the prime minister’s commitment to build it in full. A key NPR proposal was a new line between Manchester and Leeds via Bradford. Instead IRP proposed a much shorter line from Manchester to terminate west of Standedge tunnel. IRP does not state how tunnel capacity will be increased.

HS2 has provided strategic direction for various studies. One such study, Network Rail’s ECML route study, considers that HS2 provides a once-in-a-generation opportunity for a step-change in rail services provision that frees up significant capacity so that the ECML route can be better used. It seems that this opportunity is now to be lost owing to the flawed IRP report which has been subject to universal criticism by the rail industry and local authorities affected by it.

Want the best engineering stories delivered straight to your inbox? The Professional Engineering newsletter gives you vital updates on the most cutting-edge engineering and exciting new job opportunities. To sign up, click here.

Content published by Professional Engineering does not necessarily represent the views of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers.