The idea behind cloud computing is as old as the internet. Taking its name from diagrams showing how a circle of computers could be linked, thus illustrating the concept of the internet, the notion of a cloud is also handy in implying to users a skyward direction for their data; off to be crunched elsewhere.

Essentially it boils down to using computers that are not in your building, accessing your data over the internet through a web browser. This means outsourcing computing needs by renting server space on which to either store or process your work. As well as not having to buy and maintain expensive, powerful computers, an added bonus is that a company only rents space as and when it is needed. The latter point prompts the oft-used analogy that compares computing power with utilities. Just as users don’t know where their electricity comes from, they use it at will, paying only for that amount later.

For engineers, the theory of the cloud looks set to become all the more real, with a host of applications coming online this year, in a flurry of hyperbole. Microsoft is calling it a “new IT paradigm” that will get products to market faster, cut costs and generally help users to solve their business problems.

On a domestic level the idea of the cloud is already well established, in services like MobileMe, the online storage space for Apple’s customers, and even Hotmail and the back-up service that broadband providers offer. These are all forms of storing documents on servers located who-knows-where, accessed over the internet.

But its use in industry, where files are much bigger and needs are more complex – a particularly good example of that being engineering firms that want many users to access CAD files – is only just beginning.

Of the three big CAD software developers – SolidWorks, Autodesk and PTC – two are releasing products this year that offer greater use of cloud computing, even if it is not the central selling point for these wares.

Regardless of the hype, the cloud is certainly on the rise, says Fielder Hiss, vice-president of product management at Dassault Systemes SolidWorks. “We definitely see a shift going on,” says Hiss. He compares it to the boom in computing power that helped the early SolidWorks to grow in 1995 when the cost of desktop computers dropped and greater computing power became widely available. “We can see a similar shift potential today,” says Hiss.

SolidWorks’ first product offering this new infrastructure for data exchange will be called n!Fuze. After 18 months in development, the first live beta testing will begin in March, with a launch scheduled for summer.

“This is an online file sharing and collaboration application to allow people to upload engineering designs to share with others – not through sending emails or using an FTP site. Also, you can invite other people to have a look at the work,” says Hiss. He adds that the level of access can also be controlled so that some staff can change designs, others can only observe. Access is possible through either loading an add-in to existing SolidWorks software or through a browser.

Hiss says this is solving a number of problems for smaller companies. As most of these operations lack a full IT infrastructure to enable and maintain this level of interactivity, n!Fuze offers a short cut. “It lowers the barrier to entry. They go online and pay and go through there so they don’t have to think about installation of services or infrastructure,” says Hiss.

SolidWorks is also developing an app to allow access via an iPhone or iPad, although not for designing. “It doesn’t make sense to do CAD work on an iPhone. But for a manager that is now able to view work while away, and can give their approval online, that makes sense. They are no longer the bottleneck,” says Hiss.

Regardless of these benefits, all the vendors agree that security concerns will slow wider adoption of the cloud. The notion of putting all of a company’s designs and intellectual property (IP) onto a server that might be on the other side of the world is simply too frightening for some.

“Initially, the scepticism will be surrounding security,” says Hiss, accepting that overcoming this might take some time. He adds that the security precautions taken in accessing the cloud are much tougher than most companies’ own firewalls. “Disaster recovery is significantly better than most companies’ operations too, because we back up in real time,” he adds.

Security concerns are also flagged up by Steve Bedder, manufacturing technical manager for UK and Ireland at Autodesk, maker of the AutoCAD range of products. “We’re always working to reassure customers and this is why we hold all the relevant security certification and use 256-bit encryption,” says Bedder.

He claims security is at the forefront of the minds of Autodesk developers, to ensure that a company’s intellectual property does not end up in the public domain. “If someone loses their design data it could break that company,” says Bedder.

He reports that his contacts in manufacturing are aware of the talk around cloud computing but are wondering what it will mean to them. He says Autodesk’s approach is to “look at manufacturers’ needs and see if we can use the cloud in a pragmatic approach that meets those needs, rather than take all our applications and run them in a browser,” says Bedder.

Part of this process involves offering trials of AutoCAD, Inventor, Revit and Maya applications, so users can run them over the web rather than download them. This trial is called Project Twitch and, at the moment, is confined to North America.

“The whole point is to get the tech out there to individual users so they can provide feedback and suggestions for improvements to the product management team,” says Bedder. And this will see commercial products released “three or four years down the line,” he adds.

One of the key advantages, says Bedder, will be what Autodesk’s chief executive Carl Bass calls infinite computing. “This is utilising the power of the cloud to allow design engineers to do more in a shorter space of time,” says Bedder.

He gives an example of an engineer running finite element analysis (FEA) on a design. “That could take half a day to set up the FEA and two days of computing to come to a decision and say those are the parameters I’d like to change,” says Bedder.

Through using the cloud, you would “send it off to server farms to crunch the numbers. It works in a very short time as we are utilising server farms with hundreds of gigabytes of memory. We’re talking about results in minutes.”

Brian Shepherd, executive vice-president of product development at PTC, which makes Pro/Engineer 3D CAD software as well as a host of other, broader product lifecycle management products, says he hears more talk of the cloud “from cloud providers than customers. We’re trying not to get swept up by the hype cycle. We are neither advocates nor detractors,” he says.

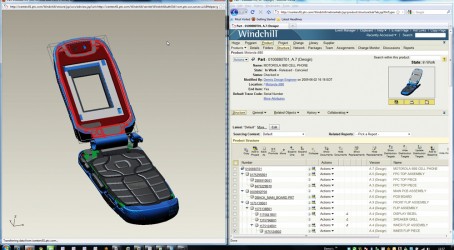

Unlike the other two companies, PTC is not currently in the process of developing cloud-based products (although Shepherd points out that its Windchill product has allowed collaboration over the internet for more than 12 years) but is concentrating on rebranding all its activities, including its latest version of Pro/Engineer and Windchill, under the name Creo.

Shepherd also flags up the potential need to increase the capability of a user’s Wide Area Network so it can handle the amount of data being moved around, changed and synchronised constantly. “Product development engineers use very large flies, of hundreds of megabytes. If we’re really storing CAD data in the cloud, WAN performance is going to be an issue. And that doesn’t come for free,” says Shepherd.

He adds that, at the moment, most PTC clients that use the cloud are small to mediumsized businesses, and they only make up a small part of its business. “The cloud is not a meaningful part of our revenue at the moment. To us it’s a deployment capability and it’s a little like whether the client uses Windows or UNIX. It doesn’t matter to us,” says Shepherd.

This ambivalence towards the cloud sets PTC against the prevailing wind felt by SolidWorks and Autodesk, a move that may not be as risky as it appears. “Frankly it’s not really a solution for many of the problems of our customers,” he says.

But then again, trends in computer usage can change. What was unthinkable 15 years ago, when emailing data felt like it carried a risk and internet banking was unheard of, has become the norm. And, as SolidWorks’ Hiss says, people used to say that the level of interactivity now possible over the internet would never happen.

“People also said we’d never leave IP in the cloud. Never is a dangerous word. There is a shift coming. We don’t know how far it will be, but we want to be where our customers will be,” he says.