The taxi driver describes driving in India as like swimming. It’s an apt analogy, up to a certain point. The constant cacophony of sounding horns and abstract lanes of traffic somehow tirelessly propel the taxi forward. The result may feel like swimming to the driver, but to the passenger, particularly one of more western origin, the sensation is more akin to being washed downstream.

The driver remains unphased though as we plough through, the roads and surroundings becoming increasingly rural out of Bangalore and towards Hosur, in the Southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Our destination is a jewellery and watch factory operated by Titan – a company that is little-known outside of its main markets in Asia and the Middle East. The firm produces, brands and sells a diverse mix of products – from spectacles, jewellery and watches to heat exchangers and parts for aeroengines.

Part of the Tata Group of companies, one of the largest and most famous conglomerates in India, Titan was started in 1986 as a watch manufacturing operation in partnership with the local government in Tamil Nadu. It has since diversified into other areas and grown rapidly. After some rough times around the turn of the millennium, when the company unsuccessfully tried to enter the European market, Titan earned revenues of $1.8bn last year. It aims to more than triple this to $6bn by 2020. The firm's ability to achieve this target is difficult to appreciate until the scale of its manufacturing operations is seen.

Titan has five watch-making plants, three jewellery-making plants and a precision engineering facility that makes components destined for the aerospace and automotive sector. The company employs 7,000 people, 3,000 of which work at the expansive jewellery and watch plant in Hosur. The plant is a preeminent example of the kind of benevolent industrialisation that the Tata Group has pursued throughout the 20th century in India. It also symbolises the approach to innovation Tata’s corporate management hopes will ensure the Group’s existence during the 21st century.

Before the Hosur plant jewellery-making was a cottage industry in India. According to Titan, craftsmen work 16 hour days to earn around £200, a month. They begin their working life at the age of 10. By the age of 14 it is not uncommon for many to suffer from eyesight and lung problems because of poor working conditions.

Meanwhile, inside the plant, employees work eight hour shifts and earn a salary of just under £300 a month. There is a union, employment terms and conditions, health and safety policies and a pensioned retirement at the age of 60. Workers are housed in a township built by Titan which has a school. Despite the clearly mundane nature of some of the work in the factory, after witnessing living conditions of the poor by the roadsides in Hosur there is little mistaking that the workers in the factory are the lucky ones.

It’s also clear that Titan has been careful not to become overly dependant on cheap labor. The company has invested considerable effort into fostering an innovative atmosphere to drive down production costs. it estimates that 30% of the jewellery division’s profits in the last few years have come from innovation in manufacturing and its integrated supply chain. Titan’s engineers share these improvements to the traditional jewellery-making processes proudly and enthusiastically.

Sommat Sood, innovation manager at Titan, says: “We are developing automated solutions for 3,000 year old processes here. Robots are not used anywhere else in the jewellery industry - but any process which is repeated - we want to automate and leave only the tasks for people which require a high amount of skill. There are things being done here that are firsts in the world”

The jewellery manufacturing process starts in the refining area – 25% of the gold sold in India is imported and recycled, around 1,200 tonnes. As well as refining, alloys are added here, such as copper and silver, to make different types of gold.

One of the furnaces used for refining gold at the Titan jewellery plant

After the refining process the modern processes takeover. Whereas traditionally it would take around 30 days to make a piece of jewellery - casting the metal using wire drawing or plate rolling, assembling and setting stones, soldering and polishing - modern manufacturing techniques reduce the time to just three days.

Engineers and designers first produce 3D CAD models using software called Rhino 3D and produce a physical model using a rapid prototyping machine. A rubber master mould is formed from this prototype to be used for volume production. The mould is filled with wax and the gold cast around the wax to form pieces of jewellery. Diamonds are set into the gold directly.

The new processes save time and improve quality in several ways, but perhaps the most impressive improvement is in the stone setting. A complex piece of jewellery can have many stones. The conventional stone setting process was slow - one person would set around 100 stones a day. The new mould-setting process allows an employee to set around 1,500 stones per day.

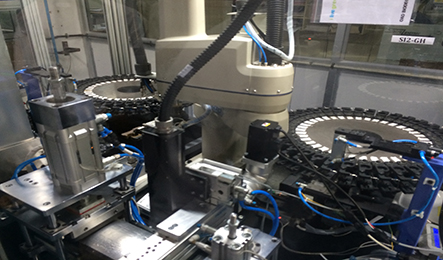

The diamond bagging machine developed inhouse at Titan

Robots are also permeating the jewellery manufacturing process in innovative ways. Centrally positioned in the factory is a new “kit marshalling area”, where stations of robotic arms pick and place jewellery components into small blue boxes ready to be assembled and polished elsewhere. The company’s engineers have also developed a machine to sort and bag diamonds automatically for each individual piece of jewellery. The process did use 40 people to pack 800 bags per day. Today the automated solution, which took four years to design and build, packs 2,500 bags a day.

Polishing is the final step of the process before packaging and is still done on an individual piece by piece basis manually, although an automated solution for this task is also being worked on.

Where the jewellery factory impresses with its new machines, the watch factory, in which 2,000 of the Hosur plant’s employees work, is an example of the type of frugality Indian engineers are internationally recognised for. Some of the machines producing the tiny components for the mechanisms, called the “movement”, inside the wristwatches, are more than 40 years old. Long rows of these old green-painted machines continuously churn out spindles, cogs, pivots and other components, some of which are tens of microns thick, grinding and drilling and stamping.

The lines of machines are mirrored by workers in the enormous assembly hall, where the movement is placed in the casing and the straps of the watches are attached. Some 400 people work in assembly - it takes 20 minutes to assemble a watch. The plant produces around 16,000 watches a day from 400 different models.

The assembly hall for the watch manufacturing plant at the Titan Hosur plant

However, one of the most interesting innovations to spring from the manufacture of watches at Hosur is not a product or a machine, but a new business division. Around ten years ago a group of engineers from the watches and jewellery plant decided that they could use the machines and expertise to make components and tooling for the aerospace and automotive sector.

Sommat Sood says the start of Titan's precision engineering business was the result of one of the company's initiatives to encourage innovation in its workforce: "We had a lot of old machines for watch-making that could still be used and we had a lot of people with the expertise required for precision engineering. So instead of making the machines extinct we entered the market.”

Since its creation Titan’s precision engineering business has grown impressively to include some stellar names as clients. It has also diversified into the telecommunications, energy and medical equipment sector. It employs 600 people, the majority of whom are mechanical and electrical engineers. Last year the company earned $40m in revenues and is growing at a rate of 30% year-on-year. The ambition in the business is intoxicating.

Sridhar NP, business head of precision engineering components at Titan says: "Within the next five years we aim to be five times our current size in aerospace and oil and gas. In automation at the moment we are 80% of the Indian market. We aim to be one of the leading automation suppliers in the world within five years."

The precision engineering business is split into two main parts. One part develops and makes components and sub-assemblies for clients in the aerospace and oil and gas sectors. For example it makes what Sridhar terms "engine peripherals" such as flanges and pipes for aeroengine makers Rolls-Royce and Pratt and Whitney.

It also supplies components to UTAS - the tier one aerospace supplier formed from United Technologies acquisition of Goodrich and its subsequent merger with its subsidiary Hamilton Sundstrand. The company is also active in the oil and gas sector and is supplying heat exchangers to UK firm HS Marston and filters to Parker Hannifan. Other clients include Thales, Liebherr Aerospace, ABB, Eaton and SKF.

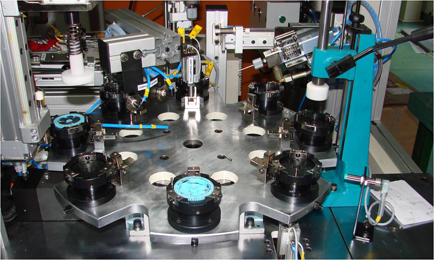

Titan's precision engineering division has several sites in India

The other part of the business develops automation solutions for assembly and test processes. This business initially grew out of work Titan did with watch-maker Seiko to automate their production lines. The tooling is sold to tier one suppliers in sectors such as automotive, aerospace and medical equipment. Clients for assembly and testing lines include Renault, Honda and Bosch. According to Titan, 70% of all the parts in any brand of car in India is manufactured by an assembly line built by the automation unit.

Despite the contrast with the other Titan businesses, which are consumer-focussed, and the steep learning curve required to work in sectors such as aerospace and automotive, Sridhar is confident the young firm can go from strength to strength. He says: “Precision engineering is soaked into our DNA and the opportunity in the market is huge. For example in the aerospace sector, 90% of the spend is in North America and Europe right now. But the future market growth is all in Asia, where you have to get costs down to sell aircraft.

“We compete on cost with the economies of scale we can use and the new machines we can purchase. To meet the required standards in the industry we’ve spend a lot of money on consultants. Plus we’ve been lucky to have United Technologies as one of our customers. They’ve spent a lot of time and effort with us.”

Titan's precision engineering division produces components for the automotive and aerospace sectors globally

Undoubtedly underpinning success both in Titan’s precision engineering business and watches and jewellery making operations is two main factors: the low cost of labor in India, both unskilled and skilled engineering talent, plus the support and guidance of the larger Tata Group it belongs to. Innovation, and the creation of an atmosphere conducive to innovation is central to Titan. The management has learnt that it is not possible to guarantee the company’s continual prosperity on a foundation of cheap labor costs. The fervour with which the company has indoctrinated innovation initiatives into its corporate culture is as impressive as the fruits of the initiatives - a lean and innovative manufacturing process that many Western firms would be envious of and a world-class automation and component engineering company.

On the way out of the Hosur factory we pass through the innovation “office”. On every desk there is a Dyson air multiplier, the fanless fan which is a great example of design and engineering. They seem out of place, until you notice they are unbranded and flimsier looking than Dyson product. “A locally-produced version”, the guide admits. Innovation itself cannot be copied, but in a sink or swim situation it offers a life raft no matter where in the world you are.