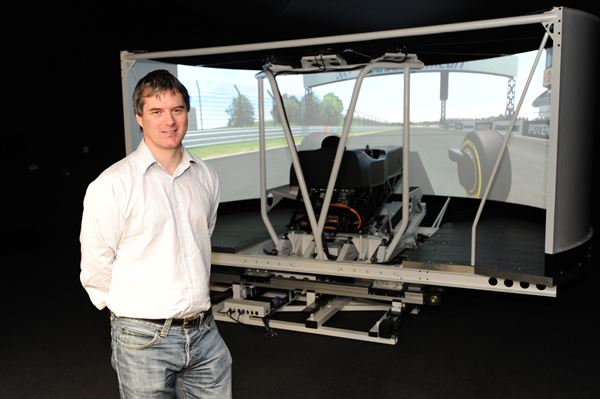

How do you become professionally registered if you work for a small company with no mentors to support you? This common problem has been addressed by the Institution with the establishment of its new independent mentor service which ‘match makes’ developing engineers with mentors anywhere in the world. One of the first Chartered Engineers to sign up as an independent mentor is Peter Hewson MIMechE, the Head of Tyres for Caterham F1. Here, we meet Peter and find out what inspired him to become an independent mentor.

If you’re a graduate engineer or an experienced technician working towards professional registration at a multi-national engineering or manufacturing company, you usually have access to a comprehensive, structured system which ensures that you have in-depth support every step of the way. If you work in a consultancy or for a small or medium sized enterprise, you might be the only mechanical engineer in the place, so how do you get the support you need to get professionally registered?

It’s a challenge that Peter Hewson is only too familiar with himself, having worked in motor sport for eight years, first for Red Bull Racing and currently for Caterham F1 – small companies which epitomise cutting edge innovation and technology but which, like all other F1 teams do not have the same infrastructure to support professional registration. He has described the independent mentor service as: “Exactly what was needed: an ideal way to help small companies tackle the problem.”

“In smaller companies, the kinds of support structures and learning facilities just don’t exist as they do in multi-national organisations. Britain is very good at small-scale niche engineering, but if you want to get into that side of the industry or are already working there, it can be difficult accessing support for professional registration and not having the confidence or knowledge to be able access support.”

“There are lots of niche industry sectors within engineering and manufacturing and lots of engineers, like me, working in them. The fact that these engineers are now signing up to be mentors and are available and accessible to young, developing engineers might give those starting out on their careers the drive to strive for that career opportunity.”

Having studied mechanical engineering first at Salford University and then at Warwick University, Peter spent the first thirteen years of his career in the automotive industry with Rover and Land Rover. Specialising in chassis engineering and vehicle dynamics, he was the Principal Vehicle Dynamicist on Land Rover’s Freelander programme, taking it from initial concept to production as part of a full six-year programme. He subsequently set up an objective vehicle dynamics department within Land Rover looking at ways to measure vehicle dynamics objectively rather than subjectively. As part of this, he was involved in seeing what methods, equipment and processes his team could use to best measure the ride and handling dynamics of road vehicles.

In 1999, when the Rover Group was split up, he went to work as a Principal Engineer at Anthony Best Dynamics, a small automotive consultancy. He subsequently became a senior lecturer at Huddersfield University during which time, he was the faculty leader for the Formula Student programme. It was this rewarding and positive experience of making a difference by helping to develop young engineers at the beginning of their careers that was perhaps Peter’s principal driver for becoming an independent mentor at this stage in his career.

He explained: “When I joined Huddersfield, given my background in automotive engineering, it was natural that I would take an interest in Formula Student. I ended up being the Faculty Leader for the university’s Formula Student programme, undertaking three competitions during my time at Huddersfield. It was a natural thing to do, but also one of most rewarding things, because it was one time when I saw the students come alive and really get interested.”

“The students had the opportunity to do something that I never did at university which was to see a practical application of what they were learning. It was invaluable to give them that opportunity to show that the theory they were learning had a practical application with a real purpose and wasn’t just bits of papers with numbers on. To see students at 2am with welders in their hands and being enthusiastic was really brilliant. I got to see a completely different side of them instead of staring at blank faces in a lecture room, so it was really good. Not that my lectures were boring, of course!”

“I see the same spirit and mentality in motor sport that I saw at Formula Student: people constantly striving and innovating but ultimately doing something that they really love to do. My colleagues in F1 have got the opportunity to do it: it’s the same reward, just in a bigger context.”

Peter observed that working in an environment where an entire business and workforce is solely focused on one aim, of making a car go faster, it is only to be expected that the culture of personal development has traditionally been below the radar, particularly in small motor sport companies. He said: “It’s a natural fact of business that everyone has a job to do and it’s a hard job that takes all your time. We’re all very focused on our job, which is to make the car go faster, so personal development often takes a secondary role. It shouldn’t do, though, because personal development is an investment.”

“If you can work with younger people, to bring them on, then eventually they will do a better job, so it’s worthwhile to do it, but you have to make a business case for it. The idea of having an independent service, where someone can take a personal interest in their own development and help another person, is just a brilliant thing.”

“It’s difficult for smaller companies – which is what most motor sport companies are – to have that kind of support structure for personal development and to have access to facilities and materials required for life-long learning. It just doesn’t exist in motor sport: it’s very much down to the individual to do it themselves, and with the best will in the world, without the support structures, it’s very difficult. The independent mentor service is a very good initiative to put in place the help and support that people need to do that.”

Working with inspirational mentors benefited and enhanced Peter’s career and left him with experiences he has never forgotten. He said: “There are certain very respected people in the field of vehicle dynamics and they are always the people I’ve respected, looked up to and wanted to emulate to some extent. Chassis engineering and vehicle dynamics are such a niche area of engineering and generally the wider public is not aware of engineers who do these sorts of jobs.”

“One or two people have burst out of that and have become more well known, and one of those is Dr Alex Moulton. Among his many achievements in engineering, he worked with Sir Alec Issigonis on the Mini: Alex did the vehicle dynamics engineering and Sir Alec did the design and the packaging.”

“When I went to work in consultancy after leaving Rover, the company I worked for, Anthony Best Dynamics, was set up from Alex Moulton’s engineering firm by Anthony, who originally worked for Alex. I got the opportunity to meet Alex Moulton, this great engineer, toward the end of his career. What was most fascinating about the experience was that he was even more interested in me, what I had to say, and what I knew, than I was about him, and what he knew and did, despite the fact that his career and life experience was massive compared to mine.”

“It was a revelation that he was still fascinated by modern engineering, modern cars, what was going on, and he was picking my brains as much as I was picking his. That was a real inspiration for me: not just having respect for people who are older and have more experience, but also having respect for people coming up, because they have all sorts of knowledge and skills that you can learn from as well. It was a fascinating insight.”

“For me, being a mentor is as much an opportunity to learn from the next generation as passing on expertise and knowledge. It’s what I learned most of all from being a university lecturer. There is a certain amount of knowledge that you can pass on just from being on the planet longer than they have, so you’ve built up a certain bank of learning and knowledge that they haven’t got. You always had to remember, however, that they were just as intelligent as you, had just as much to offer, and had so much enthusiasm.”

“It was very refreshing that they were always capable of asking questions that would make you think and keep you on your toes. I like that, and it’s an important discipline for engineers as they go through their careers to be reminded constantly of what it was like to be 20! Keeping us on our toes is one of the useful things that attracts me about being a mentor: being able to work with young people and being reminded of that enthusiasm.”

Tyre dynamics, perhaps the most complex aspect of vehicle dynamics, has been Peter’s area of expertise for over ten years. He explained: “The challenge of trying to turn tyre dynamics into an objective, scientific study was very interesting for me. I really started to focus on it during my time at Huddersfield. When I went to Red Bull Racing, it was what they were interested in, as well: putting objective numbers behind tyre science. For Red Bull, and for the past three years for Caterham I’ve been trying to develop objective processes and procedures in the field of tyres, putting numbers behind what we’re doing, and being able to model them more and more accurately.”

As all Formula One fans know, there has perhaps never been a season before in the sport where tyre performance has been so closely scrutinised by engineers, fans and media alike. Peter’s insight into the issues and what that means for his job, is considered and fascinating. He said: “The tyre manufacturer, Pirelli, has done a fantastic job in F1. The company has made a huge investment in the sport, and I think we all ought to be a lot more grateful that they have supported F1 so significantly for a good number of years.”

“It’s in the manufacturer’s interests to make the tyres a talking point. Pirelli achieves that by making them a feature of the race, but in doing so, the company has an incredibly fine line to walk. The easiest thing for a tyre manufacturer to do is to make a dull, boring tyre that you put on a car and you forget about and nobody ever mentions. That’s not in Pirelli’s interest, because they would never get a return on investment. To their credit, they have tried to make the tyres interesting by making the tyres have a relatively short wear life and relatively high performance so that it’s a requirement of the teams to understand the tyres, and it’s not an easy thing to understand. That’s why my job is interesting because it’s a challenge to understand the tyres. This is Formula One, so it shouldn’t be easy, it should be a complex and challenging task.”

Because the independent mentor service is largely facilitated digitally via online networking, it has the potentially to be hugely beneficial to motor sport and F1 teams which are renowned for the extensive international travel which their employees undertake. Peter said: “The new service brings opportunities to do things differently, online could be a new opportunity. I’m in my forties now, but there are lots of engineers around now who are younger than me and who are much more au fait with the digital world. While my first instinct is still to think in terms of face to face relationships, and pursuing career development via old fashioned printed media, the next generation of engineers will think of it as absolutely normal to be FaceTiming on phones, Skyping mentors and doing everything via social networking. I feel strongly that one of the things about being an engineer is keeping up to date with things, and it’s a natural progression that it will go in that direction. It’s interesting from my perspective, because it’s a development opportunity for me to keep up to date.”

Summing up his passion and commitment for being a mentor, and why the independent mentor service is absolutely the right thing for him, Peter said: “The thing about motor sport is that it is very much a personal thing: you choose to do it, put the effort in and make that commitment. In many ways, you have to be a selfish person, an individual with the confidence and knowledge to know that you can do it. So, it’s always personal choice, and mentoring is a personal choice as well.”

“I look back on my time as a lecturer and think how rewarding that was: the opportunity to help in the development of youngsters to try and give them a helping hand at the beginning of their engineering career. Of course, I always tried to pass on a little bit of knowledge, but mainly, I was passing on a bit of confidence. That was a genuinely rewarding thing to do, and I’m hoping that the independent mentor service will enable me to do a little bit of that and undertake the development of youngsters. If I can do that, then I’ll be happy.”

“If that’s something that appeals to other, experienced engineers then the mentor service is something they should consider.”

“As a lecturer for four years, I saw a lot of students. I would take on around 100 students per year, so I probably took on in excess of 400 during my time at Huddersfield. After I left Huddersfield and went to work in F1 for Red Bull, I always stayed in touch, and kept a little eye on what the University of Huddersfield’s Formula Student team was doing. After I’d been in F1 for a few years, the university asked me to go back and be part of the revealing process for that year’s Formula Student car, which was really nice.”

“Some of the students who I used to lecture heard that I was going back and they made a special point of going back to watch the unveiling and just to catch up. I thought that was great. In your own mind, you do your job and you’re never entirely sure if you are making a difference. However, to find out years later that you did make a small difference in somebody’s life, and they did want to make the effort to come and catch up with you, was so nice because it made me think, yes, that was worthwhile.”

“I suspect that the independent mentor service has the potential to deliver the same kind of thing. If you have the opportunity to make that kind of connection and assist in someone’s development, and they can see that what you are doing is useful to them, then maybe you can make that small difference. That’s what I’m after, and I hope that’s what the independent mentor service will be.”

For more information about the independent mentor service