Articles

Explosive impact: Smith warned of the dangers of the V-2 rocket

By the beginning of 1943 Sir Frank Ewart Smith was convinced that not only were long-range rockets possible but that the Germans were well advanced in developing such weapons. He based his assertions upon reading between the lines of government reports on the Germans' military efforts and capabilities.

Before the Second World War Smith was technical director of ICI's Billingham chemicals plant, and he later became the company's deputy chairman. In the run-up to the war, ICI had planned for the production of fuel and explosives. Smith was involved in this and so gained military intelligence experience.

After war was declared, he went to work for the Ministry of Supply at Fort Halstead in Kent, as chief engineer and superintendent of armament design. While there he had a leading role in the design of PIAT, a portable, armour-piercing anti-tank weapon.

Many people did not think that long-range rockets were feasible but Smith continued to argue his case directly to Winston Churchill: his team at Fort Halstead were commissioned with investigating what form such a weapon might take.

Then in April 1943, Churchill set up the Sandys Committee to study these ‘secret weapons’ and to co-ordinate a response. Apparently, Duncan Sandys and the scientific military expert Reginald Victor Jones regularly clashed on this committee.

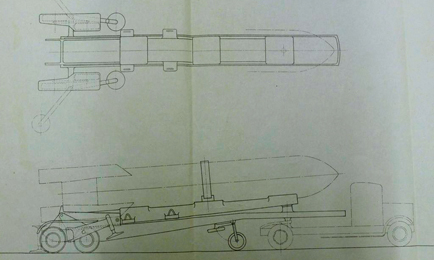

Smith studied photographs of the Germans’ Peenemünde Army Research Centre in the Baltic and reports from underground sources. These, aligned with his knowledge of projectiles and propellants, led him to produce a surmise of the weapon, which was close to the fact. However, according to G F Whitby, Smith’s colleague at Air Intelligence Headquarters, the British were not able to devise a satisfactory launching system for such a weapon.

Smith had charged Whitby with identifying the purpose of buildings and unusual civil and military installations at Peenemünde. By late 1943 Whitby was studying stereoscopic photographs and researching papers filed as “The Miscellaneous Polish Rumours”. This work led to the realisation that the German launching system had been misunderstood. The team realised in April 1944 that they had been looking at the shadow of a V-2 stood vertically with no visible support structure. Squadron Leader Kenny recalled seeing an article by German rocket developer Wernher von Braun for the Interplanetary Society detailing his proposed method for a vertical launch. (It was discovered after the war that the article had been seen by Hermann Goering.)

This realisation led to a full reconstruction of the launching and control system being made. This allowed Smith to press hard via Sandys to the War Cabinet, who responded by attacking possible launch sites from where British targets would have been most vulnerable. These interventions were a “considerable influence in the decision to drive the Germans out of the Pas de Calais area as soon as possible” to stop the Germans making launchings on these targets; the site was likely to be more effective than those eventually used from September 1944. The V-2 rockets were launched from deep inside occupied countries from mobile launchers.

The first to be launched in warfare was aimed at Paris. For six months they would be launched at London and other cities in Britain, as well as cities in northern Europe newly liberated by the Allies. Their impact was psychologically powerful on the at-home populous, who had already endured the Blitz.

The mobile nature of the V-2 and its speed once launched made it difficult to detect, destroy and warn against. Therefore, limiting its effectiveness by forcing launches away from the south coast was one of the few defences the British could deploy against the rockets.

The V-2 – or Vergeltungswaffe 2, Retribution Weapon 2 – was the world’s first long-range ballistic missile. It is estimated that more than 3,000 were launched at London, Antwerp and Liège. After the war, allied forces raced to collect examples of the V-2 and the scientists who had worked on them. Post-war developments led to Soviet and American versions, descendants of which became intercontinental and nuclear.

Smith returned to ICI after the war, until his retirement in 1959. In 1957 he was made a fellow of the Royal Society.