Coined by Sierra Space CEO Tom Vice in 2022, this new era marks the transition, he said, from 60 years of space exploration to true space commercialisation. Brought about by the rapid privatisation of space services – powered by reusable rockets and falling launch costs – and accelerated by rising geopolitical tensions on Earth, it heralds the dawn of a radically new way of using orbit.

Instead of a “handful of astronauts” flying to government-run space stations, Vice wrote, we will soon see thousands of workers flying to commercial space destinations to work in microgravity factories in sectors such as biotech and energy.

Colorado-headquartered Sierra Space aims to take a lead in this brave new off-world economy. It is doing so with two radical new takes on critical components of orbital systems.

The first is the Dream Chaser spaceplane, an uncrewed, autonomous and reusable vehicle that will transport and return cargo from space. Tenacity, the first spacecraft in a planned fleet, is due to launch on the first of seven resupply missions to the International Space Station (ISS) later this year.

The second component, still a few years away from launch, is Life (Large Integrated Flexible Environment). A revolutionary reimagining of how to house humans in space, the space station habitat is made of woven fabrics that are inflated once in orbit, providing more space for living and working without a massive increase in weight or transportation requirements.

The company’s aim is nothing less than creating an entire space “ecosystem” for this new industrial age, says Shawn Buckley, vice-president of destinations, to Professional Engineering. “Sierra Space differentiates itself from virtually any other company,” he claims. “We have the plane that goes to our space station, we have the space station, and then we're developing the systems inside the space station.”

Together, the elements could transform humanity’s use of the orbital environment.

Rapid recovery

Microgravity manufacturing offers a way of reducing product defects and creating ordered structures that are impossible to build on Earth. Potentially suited for bioprinting and electronics, the process could soon transition from small-scale experiments to a genuine economic opportunity – but it brings a new set of challenges.

Chief amongst these is safely transporting specimens, and eventually complete products, back to Earth. Sierra Space aims to enable that with a soft landing that puts cargo through forces of only 1.5G, according to chief safety officer Angie Wise. The spaceplane design – unlike a capsule – means that the Dream Chaser can land on runways that are 10,000 feet (3km) or longer.

“The scientific community would prefer to have that gentle reentry, especially when we're starting to talk about things like 3D printing in space, and crystal growth, because we don't want those to collapse on landing,” says Wise. “The current capsules that are out there providing cargo do have a harder landing into the ocean, and then it can take significant time for them to recover those vehicles from the ocean and fly the hardware back.”

She adds: “It takes us about 30 minutes for the vehicle to cool off… for these NASA missions, we actually land at Kennedy Space Centre, so that they can immediately get the goods off and then into their labs.”

Key features of the design include folding wings, which minimise the amount of space the craft takes while stowed in a 5m rocket fairing before unfolding in orbit. Describing it as “the first folded wing design in space”, Wise is tight-lipped about specific engineering features of the wings’ locking mechanism, but says it is “novel for space”.

Combined with a detachable 4.5m cargo module known as Shooting Star, Dream Chaser will carry more than five tonnes of cargo to orbit. The module will detach before reentering the atmosphere, where it – and a fresh cargo of waste – will burn up.

While the first Dream Chaser is uncrewed, Sierra Space aims to eventually carry crew to and from the space station and other low-Earth orbit (LEO) destinations in future generations.

The inflatable space station

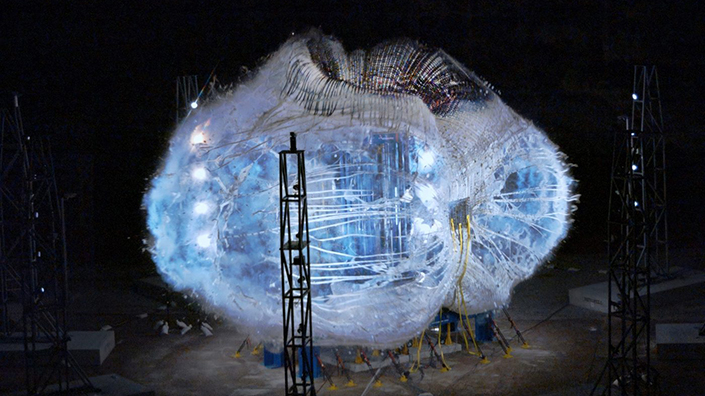

Some of those destinations could be the company’s own Life habitat. Based on ‘soft goods’ expandable technology, the habitat has been in development for over 15 years. During launch, the textiles will be packed tight around a hard core in the centre. Once in orbit, a 40m3 package will be expanded into almost 300m3.

“This gives us a large amount of volume,” says Buckley. “Talk to anybody who’s been to space, the astronauts – they will always say ‘There's not enough space in space, there's not enough space to do experiments, to live, to be able to move around’.”

He explains: “You press a button and basically a pressure control system inflates this volume… On first ingress, our inhabitants will go inside there and unpack that core, which has thousands and thousands of pounds of equipment and facilities.”

Hearing the phrase ‘inflatable space station’ does raise a rather concerning possibility – what if it is hit by space junk? Would it burst like a balloon, putting occupants in immediate danger?

Thankfully not, says Buckley. The company is working with NASA to ensure it can track debris, and the chosen materials are designed to prevent damage.

“Our pressure shell is made out of Vectran,” he says. Assembled in a ‘basket weave’ architecture, it is reportedly stronger than steel. “We can inflate this to these high pressures, and it's extremely strong.”

Outside the structural layer is a series of soft goods, which protect the inside from micrometre orbital debris. “It's lightweight, it's robust,” says Buckley. “It basically breaks the debris up on the first hit on the outer layer, and then the other layers catch it.”

The resulting damage, therefore, should be much less dramatic than the video of the habitat being over-inflated. Further ‘creep testing’ forecasts that the materials should last for 2m years at operating pressure.

-dec-2023.png?sfvrsn=85fe4611_0)

Before...

... and after bursting. Operational damage should be far less dramatic, according to Buckley

The company, which is targeting 2028 for a first launch of Life, hopes its approach could provide more space in space. Future generations will be even bigger. “In a single launch we can put 4-5,000m3 in space. The International Space Station is 1,000m3,” says Buckley. “It's gonna change everything in space.”

Scratching the surface

By providing capabilities across the spaceflight and habitation ‘spectrum’, Sierra Space avoids reliance on other companies for services such as transportation. Commonality of parts between systems also ensures that they should interface and work together smoothly, boosting reliability.

“We have systems which provide power. We have systems which provide the thermal dissipation, so you don't overheat while you're inside the habitat. We have systems which allow you to communicate, the guidance. All of those systems encompass our Life habitat,” says Buckley.

The Sierra Space team with the Dream Chaser

Together, Dream Chaser and the space station could provide a complete orbital solution for nations and private customers, making space more accessible.

“I think we're just scratching the surface of the Orbital Age,” says Wise. “These systems are going to allow for more people, more diversity of people, diversity of experiments.

“There's so many pharmaceutical implications of being able to do experiments in microgravity, 3D manufacturing – I don't even think that I can fully imagine all of the different things that can start coming out of this space economy.”

“It’s the next Industrial Age,” agrees Buckley. “We see hundreds, thousands of people working in space and living in space. And not just in LEO… I look at the Moon, and I think ‘There's going to be an inflatable habitat on the Moon, I'm going to do this in my lifetime.’ It's going to happen from here at Sierra Space. And our technology serves deep space.”

Want the best engineering stories delivered straight to your inbox? The Professional Engineering newsletter gives you vital updates on the most cutting-edge engineering and exciting new job opportunities. To sign up, click here.

Content published by Professional Engineering does not necessarily represent the views of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers.