The workhorse of the skies is getting a makeover. The Airbus A320, the European aircraft company’s best-seller, is to be produced in a new version, the A320Neo, by October 2015. The new airliner will offer 15% fuel savings, a 15% cut in CO2 and 50% less NOx emissions, and a 15dB noise reduction compared with today’s A320.

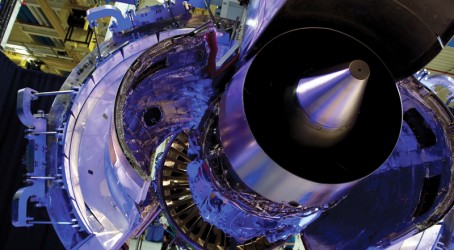

Neo stands for New Engine Option, and it’s the engine that will deliver most of the advancements. “It’s not really the airframe side that creates the big breakthroughs in fuel savings,” says John Leahy, Airbus’s chief operating officer. “It’s coming from the engine technology.” Two new engine options are being offered by Airbus to its customers, and they represent contrasts in engineering and in philosophy.

In this contest between two engine makers, Pratt & Whitney is portrayed as the radical innovator with its PurePower PW1100 engine. CFM International, the joint venture between GE of the US and Snecma of France, is emphasising its solid experience with its Leap-X engine.

The line-up may not look much different from what Airbus has offered customers for the past 20 years or so, although there is one significant missing name. CFM has been supplying its CFM-56 for the current A320; the new P&W engine brings in the German and Japanese firms that were involved in the IAE V2500 consortium, but not Rolls-Royce, which has opted out. “The nameplate this time is Pratt,” says P&W’s senior vice-president of engineering Paul Adams.

The real differences, though, are in technology. Pratt’s engine is a geared turbofan or GTF and is, says Adams, “a new kind of product offering in the commercial aeroengine space”. In simple terms, the GTF puts a gear system between the fan and the low-pressure compressor, which means the fan operates at a lower speed and enables the optimum bypass ratio to be increased to 12:1 or even a bit higher.

“The gear system means we can optimise the fan and the low-pressure compressor which enables us to take the bypass ratio beyond where historically it would have been optimised at,” says Adams. “This has a direct effect on propulsion efficiency so that ramifies itself into a lower fuel burn.”

P&W says it is saving 16% in fuel compared to what it achieves with the V2500, and that feeds through directly to a 16% CO2 emissions cut too. It’s also using its Talon combustor technology with fast quenching to cut NOx by around 50%. Adams is wary about claiming that these figures are exactly what any airline operator will get, but they are similar to what Airbus quoted in its A320Neo publicity launch.

They’re also, though, much the same figures that CFM, the GE and Snecma combo, is quoting for its contender for the A320Neo, the Leap-X. CFM, though, is scarcely concealing the fact that it sees Pratt’s GTF philosophy as dangerously radical, contrasting with its own measured approach.

“We are drawing heavily on our experience with the GE90, which has been in service since 1995 and has logged more than 20 million flight hours, and the GEnx, which will enter service this year,” says Ron Klapproth, director of the Leap programme at CFM. “These engines provide best-in-class fuel burn and we are applying that same technology to the single-aisle market.”

Leap-X has a larger fan than the previous CFM designs, a 10-stage compressor and a two-stage high-pressure turbine. And CFM has used a lot of composites, advanced design in terms of blisks (bladed disks) on the first five stages, and its own advanced Taps (twin-annular pre-swirl) combustor technology, which is being used for the first time on the GEnx.

The figures that CFM is aiming to get out of its new engine are similar to those that Pratt is claiming for the PW1100. The bypass ratio is trumpeted less by CFM, but is 10:1, which is double that of today’s A320 engines; fuel savings and CO2 emissions are 15% lower, and NOx emissions are 50% below the amounts demanded by the regulations.

But what CFM is majoring on is that it has achieved these figures without a radical design change. Asked where he saw the benefits of the CFM approach against those of Pratt, Klapproth says: “If we know we can get to the same place with technology that offers less risk for our customers, why wouldn’t we use that technology?”

He goes on: “Any technology that we incorporate into Leap must pass through the reliability filter and an exhaustive test programme that encompasses each phase of development, from the individual component level to the full engine.”

In fact, different though the two engine manufacturers’ approaches have been, and however different their ideas, there are also many similarities. Both the A320Neo engines are still under development, and will be ready for late 2015, but not much before. Pratt & Whitney’s PW1000 family, of which the Neo’s PW1100 is part, has a couple of family members whose development timescales are slightly more advanced, because Bombardier for its CSeries and Mitsubishi for its next regional jet selected the GTF technology before Airbus.

“These two are still in development, but we’ve got 300 hours of testing on the Bombardier engine and about 20 so far on the Mitsubishi,” says Adams. The A320 version is at concept optimisation now, moving to complete documentation before the end of this year and testing starting in summer 2012. Certification is intended for the second half of 2014 with entry into service on the A320Neo late in 2015.

CFM is on a similar path. It has been running a demonstrator engine with a Leap-X fan mounted on a different engine for about two years and has done cross-wind, acoustics and performance testing. A first demonstrator core to test blade aerodynamics in the compressor and the interaction between the combustor and the high-pressure compressor ran last year; a second core is just starting its tests and there will be a third next year. Design freeze is due at the end of 2011 and full engine tests start in early 2013 with flight tests in 2014.

“So far, so good,” says Klapproth. “We are really happy with everything we are seeing.”

There are other similarities too: Pratt may stress its innovation, but both programmes have long research antecedents going back to the 1980s and 1990s. “We started working on the GTF in the 1980s fuel-cost crunch period,” says Adams. The work, he says, started coming to fruition at about the point a few years ago when fuel costs came back on the agenda for airlines in a big way.

But although there are elements in which the two rivals appear to be engaging in something of a phoney war, there are real divergences too. Adams is convinced that the geared turbofan is here to stay: “For powering commercial service airlines, the regional jets, the narrow-body and the wide-body markets, I don’t think we will build a conventionally configured engine again, going forward. The geared technology is very well suited for revenue passenger service operations,” he says.

In the end, of course, whether the conventional CFM approach or the radical Pratt one wins out may depend on a set of figures that will only be verified in the longer term: operational costs and particularly the cost of maintenance. Fewer stages and lower temperatures at the core mean that Adams is confident that maintenance costs on the PW1100 could be 20% down on current engines.

Klapproth, more cautiously, says that CFM is “committed to maintaining comparable maintenance costs on Leap, which is a more advanced engine, as we have on the current CFM-56”.

Airbus, sitting happily in the middle while the two engine makers compete for its lucrative business, talks gently about possible 10% maintenance savings, but adds that only time will tell. Either way, it seems to have a winner on its hands: 332 firm orders in the first three months after launch for A320Neo, and all of them going for the Pratt & Whitney engine, and predictions of 4,000 Neos in time. But these are early days.

Sharklets bite into drag

The engine contest is the real differentiator in the A320Neo, but the A320 family will have benefited by the time the new engine options come on stream from some alterations on the airframe.

Chief among these is the addition, from 2012, of what are termed “sharklets”, a variety of blended winglet which will be available on all new A320 family aircraft. They reduce interference drag and could bring fuel savings of up to 3.5% but that, says Airbus’s John Leahy, is about as far as it goes with airframe improvements.

There will be minor changes to accommodate the sharklets and then the new engines, but essentially the A320Neo airframe will have 95% commonality with today’s A320. “The market was very clear,” Leahy says. “It wanted a re-engined A320. If a clean sheet of paper would give us 3.5% better economy, and new engines promise 15%, it’s not so much a New Engine Option as a New Engine Obligation.”