Machine tool manufacturer Yamazaki Mazak is a family-run and owned Japanese business, but it is anything but parochial. The company was able to establish a factory in the US as early as 1976, and Singapore followed in 1989. For its European base, Mazak chose the UK in 1987 – and extensive manufacturing facilities are producing tools here at its plant in Worcester. Importantly, the British facilities are also a design centre for Mazak-branded machine tools. This means that they can be specifically developed for the European market and made in Britain.

Mazak in the UK enjoyed its two most successful years in 2011 and 2012, and is on course to repeat the feat this year, says Richard Smith, managing director for the UK and Ireland. He acknowledges that the machine tool industry has been devastated since its heyday. “Birmingham was the heartland of machine tool manufacturing: there was a hell of a lot going on. So the perception that we don’t make machine tools any more has some justification.”

However, what remains is going strong, he says. “The industry that is here is doing well – thriving.” That view is borne out by the Manufacturing Technologies Association, which has taken a higher level of bookings than in 2012 for its biennial Mach trade show, which is devoted to machine tool technology, and will take place next year. And while there may be some concern over consumption of machine tools on the domestic market, production is up, indicating that firms are shipping product overseas.

The reasons for Yamazaki Mazak continuing to operate in the UK are straightforward, says Smith. “It’s important to be able to react to customers’ needs and deliver product quickly, where there’s not the five or six-week transport schedule from Japan or the Far East. Second, it gives a lot of confidence to customers to see that we manufacture here. We’ve got the capabilities and technical support to serve them and we’re seen as being here to stay, rather than being a regional office that could disappear overnight.” Mazak machines are used at the factory to produce Mazak machines – a further confidence boost. “They can see our machines being used to manufacture our own parts,” he says.

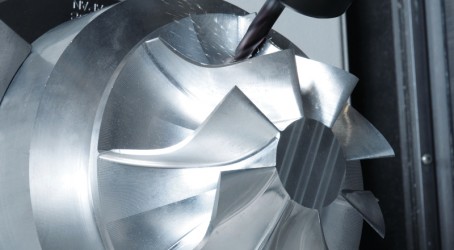

Mazak’s design engineers will be looking at making machines quicker and more accurate at a lower cost, with accompanying service and support packages. “The ability to do more processes on the machines is always interesting to customers,” says Smith.

“The whole concept of lean manufacturing revolves around not having waste; waste is often having multiple set-ups or - material that is sitting there waiting to go on to a machine. Anything that eliminates that is going to be useful – whether in improved kinematics or doing more in one operation.”

He says the much-hyped additive-layer manufacturing (ALM) is not an immediate threat to the type of subtractive manufacturing carried out in high volumes by machines such as Mazaks.

Smith believes it’s an optimistic time to be involved in manufacturing. “What is going on in government circles is not just rhetoric: I think there’s a real belief that manufacturing is a key element of our economy and can help get us out of the mess we’re in.”

Mazaks are among the first sights you see at the factory in Miskin near Cardiff of another machine tool manufacturer, Renishaw, on a site formerly owned by German giant Bosch, which used it to make alternators for the automotive industry. Bosch announced it was closing the plant in 2010 with the loss of 900 jobs – regarded as one of the most significant blows to Welsh manufacturing industry in recent times. Around £21 million of public money has been poured into the huge site since it was established in 1991 – Bosch sold it to Renishaw for £7 million, with the latter also incurring £700,000 in stamp duty. It is thought that Bosch determined it could produce alternators in Eastern Europe at a third of the cost of the UK – and that it was economic to move production despite the destination plant being two years away from shutdown.

Not many former Bosch employees are now working for Renishaw in Miskin – perhaps about 20. The site, which is still being refurbished, is likely to be ultimately skewed in favour of machines rather than people, with operators able to manage the output of several machines single-handedly, and those machines working around the clock. Reduced staffing is likely to help keep the plant economic, but so is investment in processes and technology. Renishaw envisages filling the buildings with machine tools – arranged in special cells that feature the company’s own metrology equipment – in due course. A combination of these factors, a favourable tax regime, and, interestingly, the availability of the Patent Box scheme, led it to pick the UK for the factory and purchase the Cardiff site, it says. The relative proximity of the site to its other British operations also helped.

The Miskin factory includes an electronics line, a dedicated area for the production and assembly of the company’s ALM machines, and a suite of metal-cutting tools to be used to make metal components for Renishaw’s precision measurement systems. The site is intended to provide the company with extra capacity with an eye on long-term manufacturing needs – many of which, it believes, are likely to involve the manufacture of additive-layer machines.

Robin Weston, marketing manager for the company’s new additive manufacturing products division, says that although the industry is in its infancy the time is right for the company to get involved. He had previously run an independent ALM business that was subsequently acquired by Renishaw. Now his machines are being made at Miskin. “To have the support of an organisation such as Renishaw will take our technology to the next level,” he says.

When his business was acquired, there were some raised eyebrows, but there should be no problem for customers, he says. “All the customers that we serve with our technology should be able to use additive-layer techniques in the right applications. Renishaw should be a leader in the field.”

The ALM machines that Renishaw is now building at Miskin process cobalt-chrome, aluminium and titanium. The manufacturing chamber can build to a maximum of 360mm in height, and delivery times are around four to six weeks. In future, larger machines will be needed, new materials will have to be introduced, and there will have to be improvements to the speed, reliability and quality of the process. “The ALM machines that are on the market are in their infancy. The devil is going to be in the detail,” says Weston.

Smaller, more entrepreneurial regions have been the early adopters of the technology. But larger sales areas will need systems in the future, and China is a particular area of interest for Renishaw because of its existing sales and technical support network. Europe is likely to be the most challenging market for the company because Germany took an early lead in ALM technology, and has the benefit of its widespread adoption among the Fraunhofer research institutes.

Weston says that when ALM cells are used to produce greater volumes of components, they will need a much greater level of automation. This is also the view of Ian Campbell, co-founder of Innovate 2 Make, an additive-layer specialist in Leamington Spa. Campbell, whose background is as a design engineer in automotive and aerospace, and his two colleagues, took the brave move of starting up the business with their own money during the recession. They invested in an ALM machine from Germany’s EOS and a substantial premises on a business park, which they fitted out themselves.

The company aims to develop an automated production cell that could one day be transplanted into the OEMs for which he used to work, says Campbell. “What we will have ultimately is one 3D printing machine at the centre with all the equipment, processes and machinery around it – and then that can be adopted at Jaguar Land Rover or Moog Aerospace and used for mass production.” He says there is no point addressing the need for machines with larger build areas or additional machines for volume production without addressing the automation requirements of such systems. “It isn’t a case of having more 3D printing machines. It’s about the powder supply: it’s no good scooping it in with a shovel – you need a continuous feed. You need the build platforms that each design requires to be transported in and out of the machine automatically. If you’re going to put these components on every Jaguar on the production line, these are the kinds of system you need.”

Innovate 2 Make is breaking even by processing requirements for small batches of components for motorsport and other sectors. The intention is to demonstrate some of the power of designing for 3D printing. Campbell shows PE an aerospace component that has been completely redesigned using ALM: it’s full of chambers and holes. The effect is aesthetically rather nice, but it’s the fact that it is 50% lighter than the original, rock-solid, design that will have the OEMs salivating. “We haven’t come across a shape we couldn’t make yet using this technology,” he says.

Despite Campbell and his colleagues having been unable to find backers for their venture among the private equity sector, high-net-worth individuals or banks, he says that the substantial publicity the 3D process has attracted has been massively beneficial. And he sees the technology as a leap forward. “Are people right to call this the next industrial revolution? I think so.”

The technology could make a huge difference to the way products are designed. “I’ve done design for manufacturing my whole professional life. I sum it up by saying that everything around us today is the way it looks because that’s how we can make it. If those manufacturing constraints were removed, things could and would look very different.

“One of the challenges for engineers is to free their minds and think creatively: to embrace the artistic flair you can enjoy with this technology.”