There is an accepted problem that the education system does not produce enough people who are interested in engineering careers. Most educators would admit that a main reason students avoid engineering-related subjects is because there is a misconception about what an engineer does. Perhaps that is because the term covers such a broad spectrum of jobs, from the person who comes to fix your washing machine to the person who designs the engines of the aircraft that take you on your holiday.

Many professional engineers suggest that the term should be protected by law, as doctors are, to improve the profession’s image. But there are other ways to promote the appealing aspects of the job to attract young people. The use of Computer Aided Design (CAD) in schools could provide one of the biggest recruitment boosts to the engineering sector yet.

All major engineering software vendors provide their software free or at heavily discounted rates to students. Traditionally, these were university students who had already chosen an engineering-related subject. But increasingly, says Joe Wilkie, education business manager for SolidWorks in Europe, CAD software is being used in classrooms before university level. “We’ve had a lot of success at getting our product into schools,” he says.

He adds that he knows of teachers who have given the software to five and six-year-olds with no problem. “We’ve yet to find an age of student who can’t use it,” he says. “Older teachers are always amazed at how quickly students pick it up. People who are young today have grown up with things like social networking and 3D gaming. When they get our software it’s not such a massive learning curve.”

The natural place for CAD to be taught in a secondary school is the design and technology classroom, where it can be presented as the kind of tool most engineers use in their workplace every day. SolidWorks’ software is installed in about 2,000 schools throughout the UK and Ireland, with more than 400,000 licences installed in schools across all of Europe. The package is fully functional and includes the modelling software, mechanical analysis and stress testing. It is sold at a discounted rate of £700 per classroom. Students can get a home licence free.

Teachers have a couple of options to develop classes that involve SolidWorks software, suggests Wilkie. They can use the tutorials supplied with the software or download free material from the teaching community website, which is constantly developing teaching guides, tests, quizzes and PowerPoint presentations. Students (or teachers) can take an online exam for a certificate showing proficiency in the software.

SolidWorks also sponsors the F1 in Schools project, an educational programme that capitalises on the allure of F1 racing to tempt students into engineering. Students use SolidWorks to design an F1 car, then analyse its drag coefficiency using Computational Fluid Dynamics software (CFD). They then use the software again to evaluate the best way to manufacture the gas-powered car, make the model out of balsa wood, physically test the car in wind and smoke tunnels and race it in a global competition. Students also assess the environmental impact of their design using SolidWorks.

Wilkie says the programme continues to grow in popularity and gets children using complex software components. “When 10 to 12-year-olds begin to question why they have to learn maths, they do this and realise that engineering isn’t just solving maths problems but designing as well and can lead to careers as entrepreneurs or in big corporations,” he says.

Perhaps the most established CAD software in UK schools is PTC’s, which, through the government-backed CAD CAMu2008in Schools initiative, has been installed in about 5,000 schools.

The programme is run by the Design and Technology Association in partnership with PTC and is part-funded by government grants. Originally, PTC gave away a version of its ProDesktop software. Today, the company gives away fully functional versions of ProEngineer, its flagship parametric design software package. A secondary school can claim up to 300 free licences for the software after the D&T teacher undertakes a short training course. The course costs up to £400 and ensures the teacher has at least a basic understanding of the software. Around 1,000 teachers in the UK have been trained to use the software.

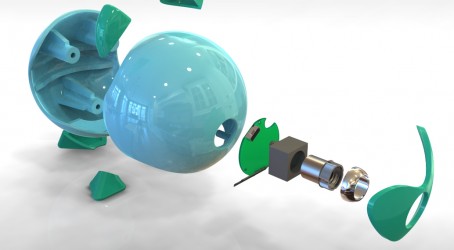

ProEngineer can perform 3D modelling, models of assemblies, mechanical simulation and analysis and photo-realistic rendering and is capable of finite element analysis. A more complete package that includes NC manufacture, advanced surfacing and manikin analysis is available. This version is also free.

PTC provides teaching materials for classes allowing students to model simple mechanisms and product packaging. Twenty projects are available, including “product” (where students can design sports bottles) to “green energy” (where they design basic water wheels). Teachers and students also have access to the commercial training material, including online videos and written tutorials.

Tim Brotherhood, education programme manager for PTC, says the most exciting project on the go is the Scalextric 4 Schools challenge, which PTC and model maker Hornby sponsors. Schools buy car kits and track for almost cost price. Students design the cars in ProEngineer, test them, make them, and race them first in local heats and then nationally in a summer competition. Brotherhood says: “They know the torque the motor provides, they program the coefficient of friction into the software and model the car on the track to see things like wheel-spin. They also do centre of gravity calculations to see how it will tip over.

“It’s huge fun and it’s affordable. Most schools do it in after-school clubs and some integrate the design and manufacture aspects into the curriculum.”

Some schools use the Mentor graphics wind tunnel software to aerodynamically model the cars, and some, extremely well-equipped, schools use rapid prototyping machines to produce the car bodies. The challenge has been running for two years and is so popular that PTC may export it to the USu2008and Australia.

Although it might seem natural to talk down the state of the UK’s school system, Brotherhood is positive about the state of CAD education. He says: “The UK has become a world leader in putting CAD/CAM in schools. The computer-child ratio here is impressive.”

When new schools are built or refurbished, PTC often works with local authorities to install ProEngineer software. “The challenge is keeping up to date,” says Brotherhood. “We provide support but schools have difficulty getting teachers out of the classroom to do the training.

“The schools find it liberating and the children get to work with the same software that commercial companies use and produce some top-quality designs that could pass as produced by someone fresh out of university.

“Getting CAD in schools tackles the misconception that engineering is a profession where you have to wear grimy overalls. It’s a gradual process – you don’t change minds overnight but this helps get the message across that doing engineering means you will be earning a good wage in good surroundings.”

“We know it’s possible to get more people into engineering this way,” adds Wilkie. “It’s our number one motivation in this market and it’s a motivation shared by education authorities worldwide. People in governments are concerned about the number of students pursuing technical careers.”