Not so very long ago, users of 3D data were a special class. Depending on the brand of computer-aided design (CAD) software that their employer had invested in, they had licences to operate the systems and certificates to prove their competence. Often, they worked at different types of machine: “Mine isn’t a computer, it’s a workstation.”

Licences and qualifications are still an important part of CAD professionalism. But CAD, 3D, PLM (product lifecycle management) and other three-letter abbreviations of engineering are no longer the exclusive preserve of the “technoscenti”: they’re going mainstream.

The process has been going on for a while and talked about for even longer. It is almost six years since Bernard Charlès, the charismatic CEO of Dassault Systèmes, talked about “democratisation” being the next phase of 3D development. He followed this prediction with the catchphrase “3D everywhere”.

For a while, outside the big automotive and aerospace companies that have always allegedly been able to afford the latest systems, nothing much seemed to happen. But now, increasingly, that omnipresence of 3D information is coming about, and there are two big factors behind this, with different players in the CAD and PLM markets leading the way on each of them.

One factor is that the complex and heavyweight programs involved, that previously needed dedicated servers and local processing power, are now much more freely available through the cloud. The other is the extension of system capabilities so that they handle not just physical product data but lots of other information, too.

Peter Thorne, managing director of the design and manufacturing technology analysis group Cambashi, says: “One side is that the vendors are broadening the scope of specialist tools. We’ve had tools that were specific to tasks such as sheet-metal and flow-in moulds for many years.” Systems such as CAD and PLM were seen – not entirely correctly – as engineers’ property. “The other side is that they’re broadening the number of functions in manufacturing that they’re relevant to,” he says.

So current moves make engineers’ data easily accessible and newly relevant to other people, and add other people’s data to the single system, forming a single hymnsheet that all can sing from.

Thorne has some doubts about the way that moves to make product and design data accessible through the cloud will play out in engineering. “If you go to most designers and say that their data will be at the far end of a network or somewhere else entirely, they’ll think that you haven’t understood what highly interactive engineering software is really about,” he says.

But, he adds, these moves by software vendors are not just about the existing engineer users and their ways of creating and manipulating product data. “If you look at Siemens PLM, one of its targets with the new HD PLM workbench is the casual user,” he says.

This may lead into new concepts such as “personal manufacturing”, where individuals can create the products they want, and which is being likened by some to the revolution in desktop publishing a generation ago.

But you don’t need to look that far. A much bigger market is an industrial mainstream that has seen itself excluded by cost and complexity from some of the previous CAD and PLM systems. This market includes smaller businesses and single operators that haven’t been able to afford the software or the computing capacity to run it. And it encompasses individuals within existing user companies who have not in the past accessed product data as such, or even regarded what they do access as “product data”, since they don’t come from a CAD background.

Cloud computing is just one of the trends making this kind of information newly available to others. An under-sung theme of CAD and PLM launches in recent months has been the exportability of data to familiar programs such as Word and Excel, so that it works on user interfaces that look pretty much like the screens we all get when we switch our machines on. The implication is clear: data that previously only engineers could access and interpret is out there for all to see and use.

It’s cloud that makes the headlines in this area, though. All of the big PLM vendors have cloud systems in their sights. But the big advocate for cloud in the CAD and PLM markets is Autodesk, which previewed its 2013 releases of design, manufacturing and architectural systems a few weeks ago. Virtually everything is now available to be run in the cloud, rather than on a server near your desk.

Pete Baxter, Autodesk’s European sales chief, says it’s the potential power of this development that is interesting: “It’s about putting world-class products into the hands of everyone.”

A late entrant to the PLM market, having been in the past pretty scathing about its rivals that went down that route earlier, Autodesk is now promoting its cloud-based systems not just as a way of getting your heavyweight number-crunching done without spending money on big computers or tying those you do have up for hours, but also as a way of unlocking product information for others to use.

And the company is bringing across into manufacturing systems ideas that it developed for its architectural, infrastructure, building management and even media and entertainment systems.

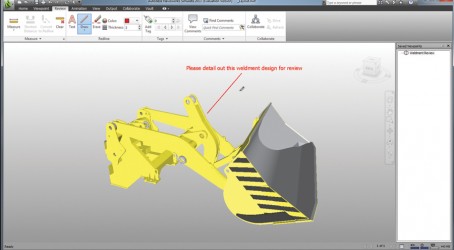

So Alan Popejoy, an engineer in Autodesk’s manufacturing division, can talk about simulation elements within the 2013 Product Design Suite as “not having the same boundaries as a CAD system”, and borrowing elements from the Navisworks building projects review software for managing complex assemblies, with data included that isn’t derived from CAD.

This kind of wider accessibility and flexibility is not dumbing down, stresses Autodesk’s simulation technical manager Shakeel Mirza, though engineers might fear this is the case. “Simulation was traditionally seen as a job for an expert,” Mirza says. “Dumbing down would not be the right solution, but there’s a big benefit in people using simulation as early as possible in the design process. So we have the engineer as an ‘intermediate’ user and the analyst as a ‘detail’ user: each should have the tool for their particular needs.”

Cloud offers the flexibility for different people to use different specialist tools on the same set of data, but it’s not the only factor that is taking product data out to a broader set of users.

PTC, long one of the big beasts of the CAD and PLM world, has been going back to basics and looking at what “product” data actually consists of these days. It has spotted a hole: a lot of product value, engineering and design effort is locked into software rather than hardware, yet traditional, engineering-based CAD-derived systems struggle to handle that.

PTC’s answer has been to buy a small company called MKS, whose Integrity system integrates software development into PTC’s Windchill PLM systems. Thorne at Cambashi describes the move as “dramatically important”, giving PTC “a significant differentiator”. Other groups are working in the same area: Dassault bought Geensoft to integrate embedded systems into its PLM systems, for instance.

PTC and others are also working on areas such as service information, quality control, and testing to bring them all into a homogeneous single system that includes the 3D and CAD data from engineers, but that will have wider business process applications. The idea, says Thorne, is that people in many business functions will be able to point, click and bring up on their screens data that started out from CAD. Whether they see it as “product” data is moot, and probably not important.

Engineers can take all this change in one of two ways. They can see it as an erosion of their hegemony over product data and their engineering mystique, or they can welcome it as an extension of their central influence over yet wider parts of their companies or organisations. Either way, it seems to be happening, so they’d better get used to it.

Cloud system brings clarity for signage firm

Beaver Group isn’t the usual kind of manufacturing customer that the computer-aided design (CAD) and product lifecycle management (PLM) companies expect: it produces digital signage, which is largely creative in content and project management, with a small “product” element in the screens its information is displayed on.

Beaver previously used a haphazard set of business process control mechanisms, including a customer relationship management system and lots of spreadsheets. Eventually, a social media contact led it to Autodesk’s PLM 360 cloud-based system.

What PLM has been able to offer, says Beaver managing director Peter Critchley, is “a way of maintaining the product details, imposing version control and tracking orders and jobs”. “We needed PLM but we didn’t know it,” he says.

Autodesk believes there are many other companies whose background is neither in CAD nor product data management (PDM) to which the new, broader types of PLM are well suited: not just big companies or traditional engineering firms.